Dublin Core

Title

Subject

Description

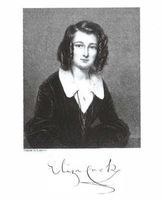

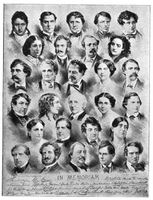

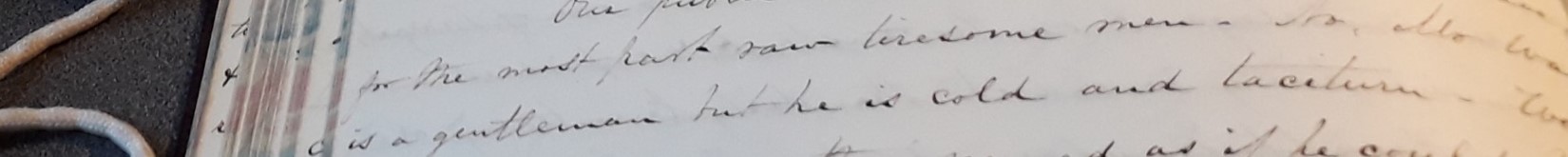

Charlotte is romantically involved with several women, among them poet Eliza Cook, writer Matilda Hays, and – for nearly two decades – sculptor Emma Stebbins (whom she met at a Shakespeare reading). Stebbins and Cushman are considered to be 'married' among those people that share some kind of intimate relationship with Cushman and know about her sexuality and relationships. Both her sexuality and her performances inspire gossip throughout her lifetime – as well as later in the twentieth century when biographers and scholars attempt to reconstruct her career and life.

Cushman proves to be a master of managing her reputation to increase her perceived respectability and to shape her public image in her favor. Performing on different stages, she travels to various cities both in the US and in Europe. She repeatedly crosses the Atlantic. She spends a considerable amount of her life in Rome where she is part of and actively shapes a social circle of women, mostly sculptors and writers. In Rome, she lives in Via Gregoriana 38. In 1869, she is diagnosed with breast cancer and undergoes surgery. In 1874, she starts her last Farewell Tour in NYC, Boston, and Philadelphia. She dies at the age of 59.

Cushman performes, among others, as Romeo, Hamlet, Cardinal Wolsey, Nancy Sykes and Meg Merrilies.

Type

Person Item Type Metadata

Birth Date

Birthplace

Death Date

Nationality

Occupation

Secondary Texts: Comments

When Hosmer moved out of the Cushman household in 1865, this had immediate consequences for Charlotte's relationship with Emma Crow Cushman: "In 1865 Harriet moved into her own apartment at 26 Via delle Quattro Fontane. While the artist boasted of the glories of her new studio, she described her home as 'modest but elegant.' She claimed to be happy with the new arrangement, but admitted it would be difficult to leave the place she had called home for five years. Cushman immediately had Harriet's old rooms renovated for Emma and her husband, Ned, who had been appointed the U.S. consul in Rome, in large part thanks to Charlotte's efforts. Emma had recently given birth to the couple's first son, Wayman. For Harriet, a significat chapter in her life came to a close with the change of address, underscored by the quick handover of her quarters. One benefit of Ned and Emma Cushman's presence in Rome was an increased incentive for the rest of the Crow family to visit Europe. Wayman and Isabella crossed the Atlantic with several of their children, including Corney, in the fall of 1865, and Harriet traveled with them to Switzerland." (Culkin 97)

About the beginnings of the 1840s and Charlotte's profession as an actress-manager of the Walnut Street Theatre, Merrill writes that Charlotte was "at a crossroads, at a point of transition from one stage in her life to another, an in the personal and professional relationships she would forge in the next few years she would come to experience and represent herself differently – more decisively – as a performer, as a woman, and as a woman who loved other women" (53).

On the issue of female sexuality in the nineteenth century, Merrill writes that for "Charlotte and many of her contemporaries the belief that respectable women lacked 'carnal motivation,' that women were somehow innately pure and more 'moral' than men, was advantageous for women in several ways. This belief created a certain sexual solidarity among women, and it allowed women into the public sphere to discharge their 'purifying' influence. And an area of society that many Americans felt in particular need of purifying was the stage" (55).

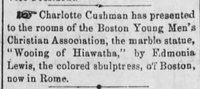

Parrott draws attention to the tradition of the American press to present expatriate women as 'Corinnes' and ambassadors. Cushman was one of them: "Fuller […] identified with the model of Corinne. […] Her death was seen by many as the inevitable tragic culmination of her non-conforming, dangerously ambitious life. […] Because Cushman was less controversial and intellectual than Fuller, her public appeal was broader. Cushman became America's preeminent improvisatrice after Fuller's death. […] The Chicago Times perceived Cushman as an 'ambassadress for America.' Her fans and reviewers referred to her as 'Our Charlotte,'"(Parrott 313)

James Maeder "arranged for her first professional appearance, in April 1835, as Countess Almaviva in The Marriage of Figaro. She joined the maeders on an operatic tourr to New Orleands, but her voice did not live up to its early promise, a failure Miss Cushman later attributed to its having been strained to develop in the wrong register. Advised by James Caldwell, manager of New Orleans' chief theatre, the St. Charles, to turn to acting, she made her debut there on April 1836 as Lady Macbeth" (Kleinfield 423)

"She was elected to the New York University's Hall of Fame in 1915, and as late as the 1940's 'Charlotte Cushman Clubs' continued to flourish in Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and other cities" (Kleinfield, "Charlotte Cushman" 424)

referring to Cushman and Stebbins as companions: "Generous and solicitous toward her friends, Miss Cushman could also be extremely possessive and domineering in her well-meant efforts to advance their careers." (Kleinfield, "Charlotte Cushman" 424)

"The public appearances of her later years did not stem, as was sometimes suggested, from an unseemly desire to postpone her retirement, but from the need to find relief from pain and forgetfulness in work" (Kleinfield, "Charlotte Cushman" 424)

About Cushman in Italy, Leach argues that "[a]bout her status among the Italians, Cushman cared not at all" (Leach 255).

Milly Williamson sketches the European context for rise of actresses to public success in relation to reputation management and gender norms in the 19th century: "Throughout the nineteenth century, the role of the theatrical star became increasingly important. After 1843, when patent protection for legitimate theaters ended, respectable theater grew. So did the power of the theatrical star, who was often both actor and theatrical manager, including female actor managers. With their growing importance, women actor managers attempted to control their own public images and present a respectable self." (Williamson, Milly. “Celebrity, Gossip, Privacy, and Scandal.” The Routledge Companion to Media and Gender, edited by Lisa McLaughlin et al., Routledge, 2014, pp. 316)

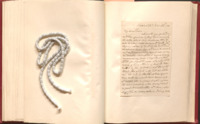

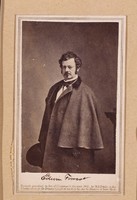

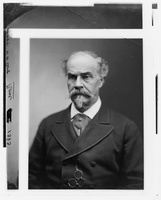

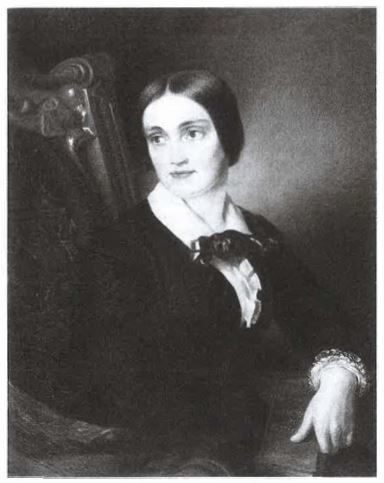

![Charlotte Saunders Cushman [graphic] Charlotte Saunders Cushman [graphic]](https://www.archivalgossip.com/collection/files/fullsize/b643c2a9e2d4693eb53ba62315de8202.jpg)