Criticism of Cushman's Performance as Romeo, May 29, 1847

Dublin Core

Title

Criticism of Cushman's Performance as Romeo, May 29, 1847

Subject

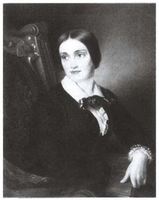

Cushman, Charlotte Saunders, 1816-1876

Muspratt, Susan Cushman, 1822-1859

Actors and Actresses

Actors and Actresses--US American

England--London

Gender Norms

Criticism

Description

Article or chapter that is dismissive of the Cushman sisters performing Romeo and Juliet; The article describes the 1845 performance as "disgustingly monstrous grossness of such a perversion" by the "transatlantic sisters." Without mentioning their names, Charlotte is characterized as the "she-Romeo being advertised as the peculiar and irresistible attraction" with "harsh features," "awkward vowel pronunciation" and a "husky voice." The author postulates that "the Juliet of Shakespeare deserves at least a man for her lover."

Credit

Creator

Fletcher, George

Source

Fletcher, George. Studies of Shakespeare. Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1847, pp. 378-382.

Date

1847-05-27

Type

Reference

Article Item Type Metadata

Text

NEW PERVERSION OF THIS PLAY, IN ITS LATE

REVIVAL AT THE HAYMARKET THEATRE

INCREASED NECESSITY FOR ITS GENUINE RESTORATION.

WHEN writing these last paragraphs, we could little anticipate such an exhibition as that which was brought forward on the boards of one of the patent theatres of London, in the following December, 1845. For the honour of our country-the country of Shakespeare—we could wish that such an exhibition should be utterly forgotten: but there are circumstances connected with that performance, which leave us not at liberty to pass it over unnoticed, but demand that we should characterize it distinctly and permanently.

First of all, then, some few weeks after the appearance of the foregoing exposition (a remarkable coincidence, to say the least) it was thought proper to abandon that Garrick version of this play which bad kept the stage unintermittedly since Garrick's time, and return to Shakespeare's text, though still with essential

mutilation& For this restoration the critics of the London press gave unqualified credit to the manager and the actors—taking occasion to treat Garrick, and his "balderdash," with especial contumely. So far, their applause of this Shakespearian revival might be very allowable. But what are we to think when we find them, while condemning Garrick's perversion on the one hand, approving on the other a violence to Shakespeare in the personation of the two principal characters, and of the hero especially, at the contemplation of which Garrick himself would have stood aghast! For the special purpose, then, it should seem, of restoring Shakespeare's work in all its purity. it was announced that Romeo and Juliet were to be personated by two transatlantic sisters—the she—Romeo being advertised as the peculiar and irresistible attraction. Had it been announced that this hero and heroine were to be represented by a brother and sister, the demand of indulgence from what ought to be the common human feelings and perceptions of any audience, would have been rather large. But in the present instance, a vastly greater demand was made: we were called upon to be interested and delighted by nothing less than the exhibition of two sisters in this peculiar dramatic relation;—and to make the matter complete, we were duly given to understand that no particular stress was laid upon the feminine qualifications of the lady personating the heroine of love—that the grand charm was to be looked for in the masculine ones of the lady representing the hero. We will waste no words upon demonstrating the disgustingly monstrous grossness of such a perversion. To any human beings, whether calling themselves men or women, who need such an argument to convince them, the argument itself would be uselessly addressed. It is idle to talk ( as we find certain critics doing at the time) as if there was nothing in the performance itself to remind one's very physical apprehensions that the soi-disant impassioned hero was a woman. That any male auditors could think so, would surely prove that we live in a time when there are men with so little manhood as to have almost lost all sense of the essentially different manner in which this passion, especially, manifests itself in the two sexes respectively—as not to feel the revoltingly unnatural absurdity, for instance, of all the hysterical sobbing and blubbering which, in even the most mannish of women, must be produced by such scenes as that between Romeo and the Friar, when the former is acquainted with bis banishment,—and more especially that of the tomb, over the seeming corpse of Juliet. To pursue this consideration in all the detail into which it would naturally lead us, would be so over—poweringly repugnant to our own taste and feeling, that we must at once decline the task,—besides that, as we have hinted already, no such exposition can be of much avail to either man so unmanly or woman so unwomanly, as to need it proving to them that the Juliet of Shakespeare deserves at least a man for her lover. We gladly hasten to dismiss this consideration altogether—to exclude from our mind (which no audience could ever do) the consciousness of the real sex of Romeo's representative, -- and, leaving aside the monstrous epicene expression of the part, to consider the essential conception of it which the actress, with such vigorous impropriety, exerted herself to realize. And here, we must say, the violence done to the moral nature of Shakespeare's hero, was quite as great as that done to his physical nature by this unnatural personation. So far from exhibiting anything of the gentle and sympathetic as well as noble and valiant spirit of the Romeo of Shakespeare,—if the she—Romeo aimed at any ideal whatever, it was an ideal of the most vulgarly selfish and headlong will and appetite.

From the beginning to the end,—whether with Benvolio and Mercutio,—with Juliet,—with the Friar, with Tybalt,—with the Apothecary,—with his own servant,—or with Paris,—there was one determined inveteracy of tone and manner,—which, with the intensely immoveable setness of look,—the ungainly, angular figure and movement,—the singularly harsh features,—the husky voice of the actress herself;—the nasal utterance and awkward vowel pronunciation of her country,—combined to produce a whole as diametrically opposed to the ideal of Romeo as we have expounded it in the preceding pages, as could have been devised even by the most vivid and powerful imagination. Nor was all this coarse, unmodulated vehemence the less startling because, so far as the histrionic heroine was concerned, it was addressed to a personage with no touch of refinement and no spark of poetry. While the whole personation was rendere but the more revolting by that very restoration of Shakespeare's words, to which the action was more than ever violently unsuited. In short, if there be anything true in such a personation,

then our previous exposition is merely nonsense.

If our exposition be right, then the manager who brought forward, the auditors who admired, and the critics who applauded such a performance, have heaped upon Shakespeare an accumulation of indignity which can be expiated only by their seeking and seizing the earliest occasion of shewing to the world that they are cured of their bad taste or have discovered their mistake.

Now, we say, more than ever, are we bound to insist that the first opportunity ought to be taken of producing on the London boards this play, most especially, with the best resources for the personation of the hero and heroine that the profession might even now afford. This, which was very desirable before, is imperatively called for now. That this piece, indeed, is one peculiarly demanding a parity of genius between the representatives of its two leading characters, we fully admit; but this consideration becomes quite secondary in the present emergency. It is no longer a question of rendering this drama adequately on the whole,—but of expelling the intensely gross misconception of it lately impressed on the minds of a large a portion of the London public,—by the only thoroughly effective means—the bodily presentment of its leading characters, true as to their general conception, and on the feminine side at least which, we will venture to say, in the great drama of Love, is the more important of the two—with richly and delicately poetic grace and refinement superadded. Let this be done, with a return bonâ fide to the text the whole text, and nothing but the text, of Shakespeare—mere verbal suppressions apart, in compliance with modern decorum,—let this once be made familiar to

our metropolitan public,—and there is little cause to fear that so unnatural an outrage on the great master genius of our country as that recently perpetrated at the Haymarket Theatre, will ever more be tolerated on the London stage.

REVIVAL AT THE HAYMARKET THEATRE

INCREASED NECESSITY FOR ITS GENUINE RESTORATION.

WHEN writing these last paragraphs, we could little anticipate such an exhibition as that which was brought forward on the boards of one of the patent theatres of London, in the following December, 1845. For the honour of our country-the country of Shakespeare—we could wish that such an exhibition should be utterly forgotten: but there are circumstances connected with that performance, which leave us not at liberty to pass it over unnoticed, but demand that we should characterize it distinctly and permanently.

First of all, then, some few weeks after the appearance of the foregoing exposition (a remarkable coincidence, to say the least) it was thought proper to abandon that Garrick version of this play which bad kept the stage unintermittedly since Garrick's time, and return to Shakespeare's text, though still with essential

mutilation& For this restoration the critics of the London press gave unqualified credit to the manager and the actors—taking occasion to treat Garrick, and his "balderdash," with especial contumely. So far, their applause of this Shakespearian revival might be very allowable. But what are we to think when we find them, while condemning Garrick's perversion on the one hand, approving on the other a violence to Shakespeare in the personation of the two principal characters, and of the hero especially, at the contemplation of which Garrick himself would have stood aghast! For the special purpose, then, it should seem, of restoring Shakespeare's work in all its purity. it was announced that Romeo and Juliet were to be personated by two transatlantic sisters—the she—Romeo being advertised as the peculiar and irresistible attraction. Had it been announced that this hero and heroine were to be represented by a brother and sister, the demand of indulgence from what ought to be the common human feelings and perceptions of any audience, would have been rather large. But in the present instance, a vastly greater demand was made: we were called upon to be interested and delighted by nothing less than the exhibition of two sisters in this peculiar dramatic relation;—and to make the matter complete, we were duly given to understand that no particular stress was laid upon the feminine qualifications of the lady personating the heroine of love—that the grand charm was to be looked for in the masculine ones of the lady representing the hero. We will waste no words upon demonstrating the disgustingly monstrous grossness of such a perversion. To any human beings, whether calling themselves men or women, who need such an argument to convince them, the argument itself would be uselessly addressed. It is idle to talk ( as we find certain critics doing at the time) as if there was nothing in the performance itself to remind one's very physical apprehensions that the soi-disant impassioned hero was a woman. That any male auditors could think so, would surely prove that we live in a time when there are men with so little manhood as to have almost lost all sense of the essentially different manner in which this passion, especially, manifests itself in the two sexes respectively—as not to feel the revoltingly unnatural absurdity, for instance, of all the hysterical sobbing and blubbering which, in even the most mannish of women, must be produced by such scenes as that between Romeo and the Friar, when the former is acquainted with bis banishment,—and more especially that of the tomb, over the seeming corpse of Juliet. To pursue this consideration in all the detail into which it would naturally lead us, would be so over—poweringly repugnant to our own taste and feeling, that we must at once decline the task,—besides that, as we have hinted already, no such exposition can be of much avail to either man so unmanly or woman so unwomanly, as to need it proving to them that the Juliet of Shakespeare deserves at least a man for her lover. We gladly hasten to dismiss this consideration altogether—to exclude from our mind (which no audience could ever do) the consciousness of the real sex of Romeo's representative, -- and, leaving aside the monstrous epicene expression of the part, to consider the essential conception of it which the actress, with such vigorous impropriety, exerted herself to realize. And here, we must say, the violence done to the moral nature of Shakespeare's hero, was quite as great as that done to his physical nature by this unnatural personation. So far from exhibiting anything of the gentle and sympathetic as well as noble and valiant spirit of the Romeo of Shakespeare,—if the she—Romeo aimed at any ideal whatever, it was an ideal of the most vulgarly selfish and headlong will and appetite.

From the beginning to the end,—whether with Benvolio and Mercutio,—with Juliet,—with the Friar, with Tybalt,—with the Apothecary,—with his own servant,—or with Paris,—there was one determined inveteracy of tone and manner,—which, with the intensely immoveable setness of look,—the ungainly, angular figure and movement,—the singularly harsh features,—the husky voice of the actress herself;—the nasal utterance and awkward vowel pronunciation of her country,—combined to produce a whole as diametrically opposed to the ideal of Romeo as we have expounded it in the preceding pages, as could have been devised even by the most vivid and powerful imagination. Nor was all this coarse, unmodulated vehemence the less startling because, so far as the histrionic heroine was concerned, it was addressed to a personage with no touch of refinement and no spark of poetry. While the whole personation was rendere but the more revolting by that very restoration of Shakespeare's words, to which the action was more than ever violently unsuited. In short, if there be anything true in such a personation,

then our previous exposition is merely nonsense.

If our exposition be right, then the manager who brought forward, the auditors who admired, and the critics who applauded such a performance, have heaped upon Shakespeare an accumulation of indignity which can be expiated only by their seeking and seizing the earliest occasion of shewing to the world that they are cured of their bad taste or have discovered their mistake.

Now, we say, more than ever, are we bound to insist that the first opportunity ought to be taken of producing on the London boards this play, most especially, with the best resources for the personation of the hero and heroine that the profession might even now afford. This, which was very desirable before, is imperatively called for now. That this piece, indeed, is one peculiarly demanding a parity of genius between the representatives of its two leading characters, we fully admit; but this consideration becomes quite secondary in the present emergency. It is no longer a question of rendering this drama adequately on the whole,—but of expelling the intensely gross misconception of it lately impressed on the minds of a large a portion of the London public,—by the only thoroughly effective means—the bodily presentment of its leading characters, true as to their general conception, and on the feminine side at least which, we will venture to say, in the great drama of Love, is the more important of the two—with richly and delicately poetic grace and refinement superadded. Let this be done, with a return bonâ fide to the text the whole text, and nothing but the text, of Shakespeare—mere verbal suppressions apart, in compliance with modern decorum,—let this once be made familiar to

our metropolitan public,—and there is little cause to fear that so unnatural an outrage on the great master genius of our country as that recently perpetrated at the Haymarket Theatre, will ever more be tolerated on the London stage.

Provenance

https://archive.org/details/studiesshakespe01fletgoog. Accessed 29 Sept, 2020.

Location

London, UK

Geocode (Latitude)

51.5073219

Geocode (Longitude)

-0.1276474

Social Bookmarking

Geolocation

Collection

Citation

Fletcher, George, “Criticism of Cushman's Performance as Romeo, May 29, 1847,” Archival Gossip Collection, accessed October 24, 2024, https://www.archivalgossip.com/collection/items/show/489.