Dublin Core

Title

Subject

Description

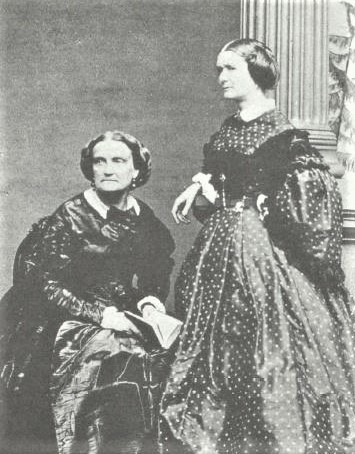

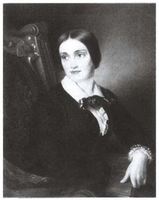

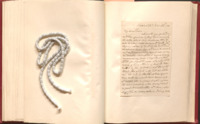

Cushman contributes tremendously to Stebbins's success in Italy as a sculptor and member of a vibrant community of artists. In July 1857, Stebbins moves in with Cushman. This relationship is the reason for Hays and Cushman to break up. While Cushman is in a relationship with Stebbins she gets romantically involved with Emma Crow Cushman. Tensions arise over time and are referred to in letters between Emma Crow Cushman and Charlotte, for instance. Cushman and Stebbins share a relationship that supersedes the other love interests of Cushman as Cushman herself expresses a 'promise' between them to care for each other and devote their lives to each other. In her letters, Charlotte also mentions a wedding ring. These descriptions feed into the often mentioned 'female marriage' between Cushman and Stebbins. Charlotte would refer to Emma Stebbins in letters to others, such as Emma Crow, as "aunt Em."

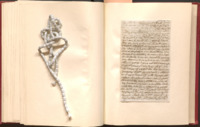

Stebbins sculpted the The Angel of Waters of the Bethesda Fountain in New York City.

For a scrapbook related to Emma Stebbins, go to Mary Stebbins Garland's (1815-1882) digitized version provided by the Smithsonian.

Stebbins's sister Caroline marries John Rollin Tilton shortly after both come to Rome in 1857.

Type

Person Item Type Metadata

Birth Date

Death Date

Nationality

Occupation

Secondary Texts: Comments

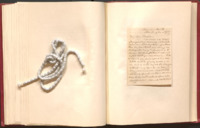

Emma and Charlotte move in together in July 1857 (Merrill 186). Both are considered to be 'married.'

For a discussion of the relationship between Stebbins and Harriet Hosmer, please go to Harriet Hosmer.

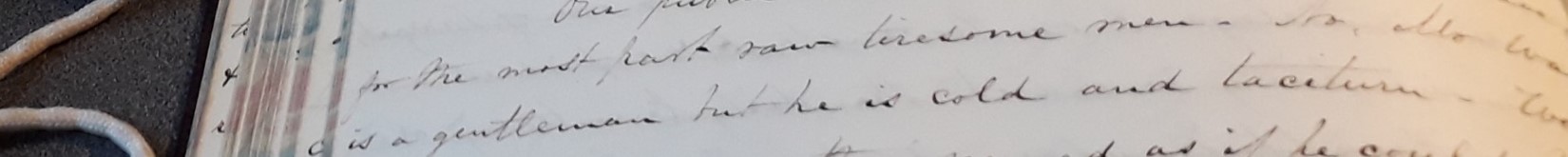

Stebbins and Charlotte - erotics of sentimental friendships, ideals:

"For some of the women in their circle Charlotte Cushman and Emma Stebbins were a visible symbol of this intimacy. One American friend would refer to photographs she had of them whenever she was 'assailed by those who believe ... that women's friendships are like pretty bows of ribbon to be put on or taken off at caprice.' […] Was is clearly evident from Charlotte's and her contemporaries' letters is that relationships of primary emotional intensity between women could be seen by some as enduring sentimental friendships, acceptable embodiments of an almost religious, morally uplifting 'sisterhood,' yet at the same time the exclusive commitment of one woman to another allowed for the possibility of intense romantic and erotic pleasure as well as precluding the female partners' relationship to men. Erotic desire was always a possible component of the narrative of sentimental friendship – so possible, in fact, that if often threatened the boundaries of that friendship, as we have seen in Charlotte's relationship with Matilda Hays and others. But, with Emma Stebbins, Charlotte enacted and 'idealized view' of women's loving relationships, which, paradoxically, appeared to many people to exemplify conventional societal values rather than challenge them." (Merrill 196)

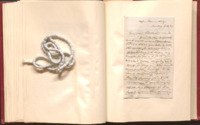

"Cushman's friendship with Elizabeth Peabody and Mary Peabody Mann, Horace's widow, enabled her to press Stebbins's claims where pressure would have most benefit. Later, when funding for the Mann commission looked precarious, Cushman offered to deliver a series of eulogies extolling Mann in some of the principal towns in New England in order to raise money to pay Stebbins for her work. Thus Cushman aimed to merchandize her own popularity and talent for the benefit of her friend." (Parrott 324)

Faderman writes that "Emma was assertive as an artist, but shy as a saleswoman. Therefore, Charlotte acted as Emma's sales agent, a role Emma had hated to play" (Surpassing the Love of Men 225). Cushman "sought in a romantic friend seems to be what most woman-identified professional women of the next few decades thought to be their ideal too–a woman who understood the demands of their occupational life because she worked under such demands as well, and who could give support and sympathy when needed, who was self-sufficient to the extent that she had a whole life of her own, but who also had energy for another, more intimate life with an equal.

Romantic friendships of this nature were especially common among academic women at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. In many colleges and universities a woman could not marry a man and remain on the faculty" (Surpassing the Love of Men 225).