Dublin Core

Title

Subject

Description

She often devotes her poems, prose writing, and newspaper columns to women's rights and and challenges gender roles. She writes gossip columns for the National Era and the Saturday Evening Post. In 1871, she starts writing for the Times as a woman travel writer. She also works for Godey's (junior editor) and Ladies' Home Journal for a short time and publishes in the Transcript and London Illustrated News. For further sources and information on Grace Greenwood as a gossip columnist, visit our "Gossip in Print" exhibit.

She marries Leander K. Lippincott in October 1853, and gives birth to Anna Grace in October 1855.

Type

Person Item Type Metadata

Birth Date

Birthplace

Death Date

Nationality

Occupation

Secondary Texts: Comments

"Greenwood skillfully uses humor in her role as a cultural critic to invite her readers to reconsider and, she hopes, revise their views on contemporary subjects, particularly as these issues relate to women." (Garrett, Prodigal Daughters 18)

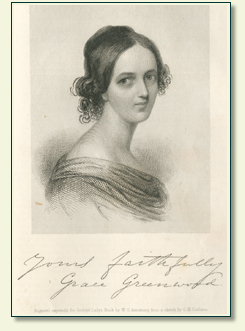

"Like many women writers of her day, Greenwood chose an alliterative, playful name, although she explained that Grace was the name her mother had originally intended for her. Sources indicate that she took ‘Greenwood’ from the name of a school in New Brighton which she reportedly attended briefly, but the school was not actually founded until several years after Greenwood had begun using her nom-de-plume. Whereas scholars have often read the use of pseudonyms as women writers’ ways of hiding their identities, Greenwood explains otherwise. In response to many requests to make herself known. Greenwood refuses to reveal her given name, insists she is Grace Greenwood, and defends the use of assumed names as a way of having a ‘name of one’s own’ (Home Journal, 16 May 1846: 2). Insistent on an individual identity, one attached to neither father nor husband, Greenwood rebuffed patronymic tradition with her eventual almost exclusive use of her assumed name." (Garrett, Prodigal Daughters 21)

"Greenwood's literary accomplishments had gained her entry into important literary circles; by October of 1849, Godey's Lady's Book listed her as an assistant editor" (Garrett, Prodigal Daughters 28)

"Her staunch abolitionist opinions, published in the National Era, created a national uproar. Afraid he would lose his southern audience after Greenwood's anti-slavery letters brought complaints, Godey removed her editorship. He restored Greenwood's name to the next issue, but Greenwood would not stand for this equivocation; she sent a widely published note clarifying, ‘I have no connection, either editorially or otherwise, with the 'Lady's Book’’ (National Era, 7 February 1850: 23)." (Garrett, Prodigal Daughters 28–29)

"At twenty-nine she was a handsome woman with expressive large eyes, a head piled high with curls, and a curiosity that kept her constantly on the lookout for subjects of popular articles. In 1850 her Greenwood Leaves had been a best seller, and her trip through Europe now was meant to pay off in more chatty articles for the American press. Hawthorne liked her, though reading the pieces she had already sent home from England, he tossed her off as a 'scribbling female' – partly because Grace took such foolish delight in attracting attention. At a private reading Charles Kemble gave in London, Grace became so moved that she almost brought down the house. At the end of one piece, she applauded so wildly that she fell into hysterics, then swooned dead away. Kemble looked up from his book. 'Ma'am, this won't do,' he said sternly. When Grace remained dead on the floor, Kemble repeated, 'Ma'am, we are too much used to this sort of thing!' When Grace still gave no response, Kemble cried, 'Ma'am, you expose yourself!' At that, Grace bounded up horror-stricken, adjusting her skirts. Hearing the story later, Hawthorne wondered how 'she survived it.'" (Leach 249) -->for the Hawthorne-Greenwood quarrel, cf. Garret's Prodigal Daughters

"In the 1850s, Greenwood had spent eighteen months traveling around Europe as one of the youngest of a group of six women. Her travel writing from this earlier expedition, Haps and Mishaps of a Tour In Europe (1853), was her most successful publication. In fact, a later woman journalist, Kate Fields, with whom Greenwood was acquainted and whose career Greenwood later encouraged, wrote of her own European travels in Hap-Hazard (1873), playing off of Greenwood's popular title. While in England in 1876, Greenwood met Fields in the home of another woman artist. Miss Philps, who apparently provided a literary salon for American writers away from the New York salon scene. Greenwood taunts readers with her independence, and the potential danger this presents, in her earlier travel writing, noting the understood threat of female independence and yet recognizing the impossibility of testing that independence on this safe, proper pilgrimage. Balancing her own fears of being a ''strong-minded woman' abroad' with the danger of becoming 'more babyishly dependent than ever,' Greenwood traverses gender as well as geographical boundaries in Haps and Mishaps, as well (Haps 49-50) . Written primarily for The Saturday Evening Post, these earlier travel letters are more playful reveries than her more serious, though still humorous, social commentary for the New York Times." (Garrett, Prodigal Daughters 178)

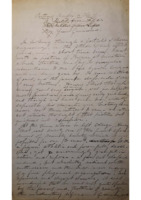

Parrott describes Greenwood as one of Cushman's 'companions' (Parrott, Prodigal Daughters 324, 327)."Greenwood wrote letters and sketches for numerous periodicals during this time, and she soon became a "special" correspondent for the National Era and occasionally for the Saturday Evening Post. In 1852, Greenwood arranged financial support for her travels abroad with Charlotte Cushman, a well-known actress, in return for letters to the National Era; many other papers reprinted or summarized her travel news, including interviews with Dickens, Browning, and Thacherey. When the National Era could not afford the raise she requested to continue her travels, Greenwood found funding from the Saturday Evening Post. Greenwood collected her travel letters to both the National Era and Saturday Evening Post in Haps and Mishaps of Travels in Europe (1854). This collection, Greenwood's best-selling work, remained in print for over forty years." (Garrett, Prodigal Daughters 30)

“Soon Grace Greenwood was writing for Godey's, Graham's, Sartain's, and the Saturday Evening Post as well as the Home Journal. She was editor for a time of Godey's Lady's Dollar Newspaper and editorial associate of his Lady's Book with its nearly 150,000 subscribers.” (Thorp 148)

Thorp emphasizes Greenwood’s interest in the personalities of politically leading figures:

“Grace Greenwood believed that she was the first female Washington correspondent. She seems to have been unaware of the fiery sortie of Mrs. Swisshelm in the Tribune, which had culminated just before her arrival, but she was, in any case, a daring pioneer and she held the field for an unprecedentedly long period, writing Washington Letters at intervals from 1850 until 1897. The early Letters are rather more occupied with the personalities of the nation's legislators than with their policies” (Thorp 153)

Thorp describes the relationship between Ticknor & Fields and Greenwood as "a warm publisher-author friendship” (Thorp 153).

"When, in 1852, she planned a tour in Europe she arranged that they should bring out in book form the Letters she purposed writing for the Era. Dr. Bailey who had been paying her $500 a year for her Letters and editorial services, was glad to have her as foreign correspondent but when she wrote from London asking him to increase the stipend to a thousand so that she might continue her travels to Rome, he declined, and in April Grace, somewhat ungratefully, transferred her correspondence to the more affluent Saturday Evening Post. ‘Greenwood Leaves from Over the Sea’ bubble with excitement and enthusiasm, detailing in tireless superlatives encounters with the antique shrines and contemporary celebrities of England, France, Germany, and Italy. As Haps and Mishaps of a Tour in Europe they made the most popular book that Grace Greenwood ever published” (Thorp 154)

Gracewood witheld personal information about her marriage and her trip with Cushman and Hosmer:

"There were even more interesting incidents in the trip on which she was discreetly silent. It was with Charlotte Cushman, for instance, that she lived in Rome; Harriet Hosmer, the sculptress, was of the party; and Grace Greenwood herself was watched during her stay by the Italian police because she was known to be a friend of Mazzini." (Thorp 155–56)

Greenwood herself became the focus of newspaper gossip: "For the explanation one is obliged to turn to a paragraph of newspaper gossip, written in 1876 when Leander Lippincott's peccadillos had swollen into crimes and he had fled the country under federal indictment. A Washington correspondent of the Hartford Times told the story of their marriage.

[Grace Greenwood's] dream of happiness was soon over, and her friends with indignation beheld the spectacle of her husband using all of her earnings for his own selfish pleasure. Loving, patient Grace, worked for both until proof after proof of his infidelities had been forced upon her. She entered the lecture field, and finally settled down in Washington as correspondent of the New York Times. Mr. Lippincott followed her to Washington and she obtained a clerkship for him in her brother's (Mr. Clarke's) office. Mr. Clarke is one of the examiners in the Patent Office. No one supposes that Mr. Lippincott made any better clerk than he did husband, or anything else. Of this situation Grace Greenwood's Letters give no hint." (Thorp 157)

"Arguing for Fanny Kemble's, Charlotte Cushman's and George Sand's right to wear trousers, for Susan B. Anthony's right to vote, and for all women’s right to receive equal pay for equal work, Greenwood boldly argues for social reform." (Garrett, Prodigal Daughters 32)

"Cushman' s wearing of breeches on and off the stage made her the subject of much public attention. See Davis 113. Catherine Clinton speculates about the nature of Cushman's relationships with two women, one of whom must be Greenwood, before her more public friendship with sculptor Emma Stebbins (163) . Greenwood was rumored to have acted on the English stage while traveling with Cushman, but these rumors are not confirmed by her letters. However, in her anonymous short story, "Zelma's Vow," Greenwood recreates her relationship with her husband, casting Lippincott and herself as competing actors rather than writers (Thorp 157). While acknowledging that there is no textual evidence of Zelma's regrets about her failed marriage, Ann Douglas Wood asserts that Greenwood 'clearly feels that her heroine is guilty' (Wood 13). Greenwood’s other writings, including personal correspondence, do not reveal a woman regretful of her success as a writer." (Garrett, Prodigal Daughters 40)

"With attention to actors and writers. Greenwood claims for women a right to a public image; she insists that it is not that women cannot or should not be seen in public, but that they have a right to define their public roles apart from male intimidation. She praises women in public roles of actresses and writers." (Garrett, Prodigal Daughters 167)

"George Sand. At the death of this French novelist, Greenwood explains that she has read all of the French accounts of Sand's death, all of which give more attention to Sand than the brief New York Times obituary. In her earlier public letters, collected in Greenwood Leaves, Greenwood had defended Sand for wearing trousers, cropping her hair and smoking cigars. Sand's behavior was the subject of much attention in the early half of the nineteenth century." (Garrett, Prodigal Daughters 168)

"Grace Greenwood fared better, though Charlotte found herself no more necessary in Grace's plan. The good journalist, Grace chose to remain in the background observing, determined to dig out the facts about Rome's coming political upheavals – though this was difficult to do, since certain parties had learned that the American Miss Cushman had forwarded money to Mazzini and, as a friend of Miss Cushman, she was suspect herself. About her status among the Italians, Cushman cared not at all." (Leach 255)

Greenwood meets the Brownings at Casa Guidi in May 1853.