Byrne's Gossip of the Century: Personal and Traditional Memories (1892)

Dublin Core

Title

Byrne's Gossip of the Century: Personal and Traditional Memories (1892)

Subject

Gossip--Published

Actors and Actresses--US American

Cushman, Charlotte Saunders, 1816-1876

England--London

Italy--Rome

Gender Norms

Intimacy--As Source

Macready, William Charles

Muspratt, Susan Cushman, 1822-1859

Italy--Rome

Description

A retrospective account of Cushman as actress and of her private life: The Memories serve as a good example for how the public image changes after Cushman's death and her success as an actress is being forgotten step by step.

Gossip of the Century consists of two volumes, Cushman is mentioned in the second after Fanny Kemble and Macready. From the first volume, the preface is interesting to contextualize the use of 'gossip.'

Gossip of the Century consists of two volumes, Cushman is mentioned in the second after Fanny Kemble and Macready. From the first volume, the preface is interesting to contextualize the use of 'gossip.'

Credit

Creator

Byrne, Wm. Pitt, Mrs., 1819-1894

Type

Reference

Auto/Biography Item Type Metadata

Text

Vol. 1: Gossip - contemporary definition

"There can be few among us who are not stirred by a feeling of sympathetic interest in the times immediately preceding ours —few who would not willingly know some thing of those whose lives, occupying part of the same century —grazed as it were our own, and whose personal acquaintance we just missed. In trying to fathom the nearer past and, so to speak, to connect ourselves with it, research seems more hopeful if we address ourselves to contemporary sources and seek our information regarding recently departed celebrities from those to whom they were personally known. The generation that can yet give us any authentic details of our immediate predecessors, is itself rapidly passing away, and as each patriarch drops out of its thinning ranks we begin to realize to ourselves the worth of our neglected chances, and to remember how much valuable testimony we have already failed to secure from those whose voice is now evermore silent, and whose knowledge is buried with them in the stillness of the tomb. The word gossip conveys prima facie, a frivolous idea; and is generally associated in our minds with what is supposed to be a congenial pastime of the more talkative if not the more reflective sex ; but all gossip is not necessarily frivolous, nor need it be malicious—though 'Méchant comme une chronique' has passed into a French proverb. History owes most of what little truth it contains, to the gossip of diarists and annotators as well as to the intimate confidences of friendly correspondence, and notwithstanding the necessarily trifling details of these private effusions and the banalités with which they often abound, the sidelights of such records have become invaluable to the groping student of past times, and of departed humanity ; nor can we possess too many such chronicles ; the value of each being proportioned to the subject of which it treats. Trifles cease to be trifles when Boswell is relating them of Johnson; besides, experience shows that while one observer collects one class of information, another applies himself to another; one will have been drawn to men of certain tastes and pursuits, another has been led to cultivate those of an altogether different type, and even where our Boswells have met in a common pursuit, we shall find they have been respectively struck by, and have dwelt upon, different characteristics in the same individual so that the notes of one form a valuable, not to say an indispensable, supplement to those of another. Contemporary memoirs will therefore always be, as they always have been, attractive, whether from their picturesque detail and often naïves descriptions, or from their unconscious revelations of private life and character, and the solution they often afford of family mysteries and historic secrets ; into these, from more or less excusable motives, we all like to plunge, and many of them can become known to us only from the traditions of the passing generation. As of celebrated persons, so also of places whose every stone has its history—and so likewise of customs already become obsolete ; the detail of such lures us back into a past that we have missed —a past which is additionally fascinating because it is past ; naturally, therefore, we welcome the living testimony which yet, but not for long, survives it. Are there any who can take a retrospective view of their past years and not experience with unavailing self-reproach a melancholy consciousness of inexplicable neglect as they recall one by one the formidable catalogue of priceless opportunities and discover for the first time how recklessly they wasted them? Full of youth and its illusions, we glanced down the lengthening perspective of the future, of which we neither saw, nor sought to see, the end ; we regarded life as a long summer's day during which the flowers that surrounded us should always be in bloom ; and we had a vague idea that we could pick them at any time. Who of those now approaching the close of life will not say with me, " What a tale I might have had to tell ! What a volume I might have been able to write, had I but taken advantage of the chances that now seem to have put themselves in my way ! " But there is a period in our lives when our eyes seem to be holden, and we must have lived, to learn the force of the exclamation, 'Si jeunesse suvait, si vieillesse pouvait !' My endeavour in the following pages,—while drawing upon family traditions to add to such personal remembrance of' of men, manners, and localities, as seem to be of broad and universal interest, —has been to exclude as much as possible in a transcript of this nature, the yet inevitable ego. If, as Pascal says, 'le moi est haïssable,' the more unobtrusive that 'moi' can be made, the better: I have therefore limited as much as possible my own part in these pages to that of a witness or giver of evidence; unfortunately, such a witness in recording his testimony as to persons and events, is compelled to manifest a certain individuality; should I therefore seem, at any time, to slide insensibly into prominence, I can only beg my readers to attribute it to the force of circumstances, and to regard the narrator simply as the harmless, necessary channel of communication." (Byrne, Wm. Pitt, Mrs., 1819-1894. v-viii)

Vol. 2: Cushman as one of the celebrities mentioned:

Remembering Cushman, touches on the process of forgetting, mentions Cushman's social circle in Rome, family members, Cushman's appearance very prominent in description, interesting nickname

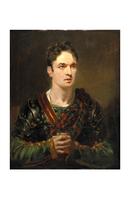

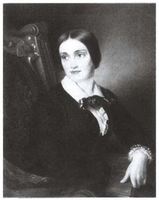

"A lady not born to the profession, nor yet qualified by personal charms to adopt it, although her histrionic theories were clever and artistic, was Miss Charlotte Cushman. Her provenance was American, and her nationality unmistakable. After seeing her on the stage in England, I made her acquaintance socially in Rome, where, in 1866, her nephew was American Consul, and I found her a most agreeable person: they had a pleasant entourage, and the house was one which all liked to frequent. They gave one or two dramatic entertainments that winter, and these little plays were extremely well got up, the acting being much above that of average amateur-displays ; the performers, who were evidently picked, were all American, and the pieces were played in English. Miss Cushman had at that time undergone an operation for a 'malignant tumour,' and was supposed to have recovered, but the insidious complaint appeared again, and I think she underwent another excision : finally, she .died of this dreadful malady, after her return to America, leaving behind her many sincere regrets. Though I had already seen her on the English stage in one or two characters, the one I remember best was at the Princess's, where she played Romeo to her sister Susan's Juliet. Susan was extremely pretty, but was not particularly gifted: in personal appearance she was altogether unlike Charlotte, who was not prepossessing either in face or figure: the latter was a large, tall, bony woman, and when she threw herself full length on the ground, an act she performed most ungracefully, her length must have represented very nearly the six-foot 'measure of a new-made grave.' I forget what was the general impression she produced on the public in Romeo, and do not know whether I shall be considered as giving proof of good or of bad taste when I say that I could not bring myself to admire the performance, though personally I liked Charlotte Cushman, and believe her to have been kindly, amiable, and excellent in every I think her friends generally must have regretted the mistake she made in rushing into public dramatic attempts, for which she was in so many ways ill-suited: she preferred men's characters, but was less fitted for Romeo than for any other: her features were most singular, and the depression of the nose gave to her countenance the appearance of having been sat upon: her face was, in fact, absolutely deformed, and it was impossible to forget it, for there was nothing in her acting either to compensate for absence of beauty, or to excuse her from placing herself in so prominent a position: she was said to be good as Julia in the Hunchback, but I did not see her in this. In private life, Miss Cushman was highly and universally esteemed, and her sad fate won for her the most cordial and universal sympathy. She was never spoken of by those who knew her but with admiration and affectionate respect, although it was pretty generally admitted that she mis-apprehended her vocation. At the same time she had excellent taste and an intelligent appreciation of art, and her counsels to stage-players were eagerly sought and respectfully considered. In her dramatic character she acquired among the profession, the sobriquet of 'Captain Charlotte.'" (Byrne et al. 429-430)

"There can be few among us who are not stirred by a feeling of sympathetic interest in the times immediately preceding ours —few who would not willingly know some thing of those whose lives, occupying part of the same century —grazed as it were our own, and whose personal acquaintance we just missed. In trying to fathom the nearer past and, so to speak, to connect ourselves with it, research seems more hopeful if we address ourselves to contemporary sources and seek our information regarding recently departed celebrities from those to whom they were personally known. The generation that can yet give us any authentic details of our immediate predecessors, is itself rapidly passing away, and as each patriarch drops out of its thinning ranks we begin to realize to ourselves the worth of our neglected chances, and to remember how much valuable testimony we have already failed to secure from those whose voice is now evermore silent, and whose knowledge is buried with them in the stillness of the tomb. The word gossip conveys prima facie, a frivolous idea; and is generally associated in our minds with what is supposed to be a congenial pastime of the more talkative if not the more reflective sex ; but all gossip is not necessarily frivolous, nor need it be malicious—though 'Méchant comme une chronique' has passed into a French proverb. History owes most of what little truth it contains, to the gossip of diarists and annotators as well as to the intimate confidences of friendly correspondence, and notwithstanding the necessarily trifling details of these private effusions and the banalités with which they often abound, the sidelights of such records have become invaluable to the groping student of past times, and of departed humanity ; nor can we possess too many such chronicles ; the value of each being proportioned to the subject of which it treats. Trifles cease to be trifles when Boswell is relating them of Johnson; besides, experience shows that while one observer collects one class of information, another applies himself to another; one will have been drawn to men of certain tastes and pursuits, another has been led to cultivate those of an altogether different type, and even where our Boswells have met in a common pursuit, we shall find they have been respectively struck by, and have dwelt upon, different characteristics in the same individual so that the notes of one form a valuable, not to say an indispensable, supplement to those of another. Contemporary memoirs will therefore always be, as they always have been, attractive, whether from their picturesque detail and often naïves descriptions, or from their unconscious revelations of private life and character, and the solution they often afford of family mysteries and historic secrets ; into these, from more or less excusable motives, we all like to plunge, and many of them can become known to us only from the traditions of the passing generation. As of celebrated persons, so also of places whose every stone has its history—and so likewise of customs already become obsolete ; the detail of such lures us back into a past that we have missed —a past which is additionally fascinating because it is past ; naturally, therefore, we welcome the living testimony which yet, but not for long, survives it. Are there any who can take a retrospective view of their past years and not experience with unavailing self-reproach a melancholy consciousness of inexplicable neglect as they recall one by one the formidable catalogue of priceless opportunities and discover for the first time how recklessly they wasted them? Full of youth and its illusions, we glanced down the lengthening perspective of the future, of which we neither saw, nor sought to see, the end ; we regarded life as a long summer's day during which the flowers that surrounded us should always be in bloom ; and we had a vague idea that we could pick them at any time. Who of those now approaching the close of life will not say with me, " What a tale I might have had to tell ! What a volume I might have been able to write, had I but taken advantage of the chances that now seem to have put themselves in my way ! " But there is a period in our lives when our eyes seem to be holden, and we must have lived, to learn the force of the exclamation, 'Si jeunesse suvait, si vieillesse pouvait !' My endeavour in the following pages,—while drawing upon family traditions to add to such personal remembrance of' of men, manners, and localities, as seem to be of broad and universal interest, —has been to exclude as much as possible in a transcript of this nature, the yet inevitable ego. If, as Pascal says, 'le moi est haïssable,' the more unobtrusive that 'moi' can be made, the better: I have therefore limited as much as possible my own part in these pages to that of a witness or giver of evidence; unfortunately, such a witness in recording his testimony as to persons and events, is compelled to manifest a certain individuality; should I therefore seem, at any time, to slide insensibly into prominence, I can only beg my readers to attribute it to the force of circumstances, and to regard the narrator simply as the harmless, necessary channel of communication." (Byrne, Wm. Pitt, Mrs., 1819-1894. v-viii)

Vol. 2: Cushman as one of the celebrities mentioned:

Remembering Cushman, touches on the process of forgetting, mentions Cushman's social circle in Rome, family members, Cushman's appearance very prominent in description, interesting nickname

"A lady not born to the profession, nor yet qualified by personal charms to adopt it, although her histrionic theories were clever and artistic, was Miss Charlotte Cushman. Her provenance was American, and her nationality unmistakable. After seeing her on the stage in England, I made her acquaintance socially in Rome, where, in 1866, her nephew was American Consul, and I found her a most agreeable person: they had a pleasant entourage, and the house was one which all liked to frequent. They gave one or two dramatic entertainments that winter, and these little plays were extremely well got up, the acting being much above that of average amateur-displays ; the performers, who were evidently picked, were all American, and the pieces were played in English. Miss Cushman had at that time undergone an operation for a 'malignant tumour,' and was supposed to have recovered, but the insidious complaint appeared again, and I think she underwent another excision : finally, she .died of this dreadful malady, after her return to America, leaving behind her many sincere regrets. Though I had already seen her on the English stage in one or two characters, the one I remember best was at the Princess's, where she played Romeo to her sister Susan's Juliet. Susan was extremely pretty, but was not particularly gifted: in personal appearance she was altogether unlike Charlotte, who was not prepossessing either in face or figure: the latter was a large, tall, bony woman, and when she threw herself full length on the ground, an act she performed most ungracefully, her length must have represented very nearly the six-foot 'measure of a new-made grave.' I forget what was the general impression she produced on the public in Romeo, and do not know whether I shall be considered as giving proof of good or of bad taste when I say that I could not bring myself to admire the performance, though personally I liked Charlotte Cushman, and believe her to have been kindly, amiable, and excellent in every I think her friends generally must have regretted the mistake she made in rushing into public dramatic attempts, for which she was in so many ways ill-suited: she preferred men's characters, but was less fitted for Romeo than for any other: her features were most singular, and the depression of the nose gave to her countenance the appearance of having been sat upon: her face was, in fact, absolutely deformed, and it was impossible to forget it, for there was nothing in her acting either to compensate for absence of beauty, or to excuse her from placing herself in so prominent a position: she was said to be good as Julia in the Hunchback, but I did not see her in this. In private life, Miss Cushman was highly and universally esteemed, and her sad fate won for her the most cordial and universal sympathy. She was never spoken of by those who knew her but with admiration and affectionate respect, although it was pretty generally admitted that she mis-apprehended her vocation. At the same time she had excellent taste and an intelligent appreciation of art, and her counsels to stage-players were eagerly sought and respectfully considered. In her dramatic character she acquired among the profession, the sobriquet of 'Captain Charlotte.'" (Byrne et al. 429-430)

Location

New York

Geocode (Latitude)

40.7127281

Geocode (Longitude)

-74.0060152

Provenance

Byrne, et al. Gossip of the Century: Personal and Traditional Memories. Vol. 2, Macmillan and Co., 1892. 2 vols., hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044036362960. Accessed 22 Jan. 2020.

Byrne, Wm. Pitt, Mrs., 1819-1894. Gossip of the Century: Personal and Traditional Memories. Vol. 1, Macmillan and Co., 1892, hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044036362952. Accessed 22 Jan. 2020.Social Bookmarking

Geolocation

Collection

Citation

Byrne, Wm. Pitt, Mrs., 1819-1894, “Byrne's Gossip of the Century: Personal and Traditional Memories (1892),” Archival Gossip Collection, accessed April 17, 2024, https://www.archivalgossip.com/collection/items/show/131.