Craik's A Woman's Thoughts on Women (1858)

Dublin Core

Title

Subject

Description

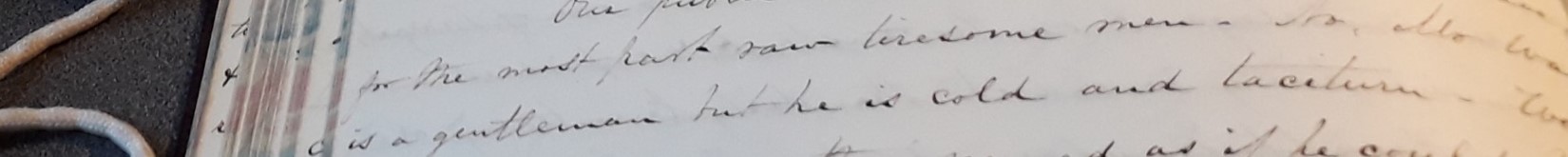

Leach indicates that Craik and Charlotte Cushman knew eacht other and met for a party.

Credit

Creator

Publisher

Date

Type

Auto/Biography Item Type Metadata

Text

Excerpts:

"Probably there are few women who have not had some first friendship, as delicious and almost as passionate as first love. It may not last— it seldom does ; but at the time it is one of the purest, most self-forgetful and self-denying attachments that the human heart can experience: with many, the nearest approximation to that feeling called love—I mean love in its highest form, apart from all selfishnesses and sensuousnesses— which in all their after-life they will ever know. This girlish friendship, however fleeting in its character, and romantic, even silly, in its manifestations, let us take heed how we make light of, lest we be mocking at things more sacred than we are aware. And yet, it is not the real thing—not friendship, but rather a kind of foreshadowing of love ; as jealous, as exacting, as unreasoning—as wildly happy and supremely miserable; ridiculously so to a looker-on, but to the parties concerned, as vivid and sincere as any after-passion into which the girl may fall; for the time being, perhaps long after, colouring all her world. Yet it is but a dream, to melt away like a dream when love appears ; or if it then wishes to keep up its vitality at all, it must change its character, temper its exactions, resign its rights : in short, be buried and come to life again in a totally different form. Afterwards, should Laura and Matilda, with a house to mind and a husband to fuss over, find themselves actually kissing the babies instead of one another—and managing to exist for a year without meeting, or a month without letter-writing, yet feel life no blank, and affection a reality still—then their attachment has taken its true shape as friendship, shown itself capable of friendship's distinguishing feature—namely, tenderness without appropriation; and the women, young or old, will love one another faithfully to the end of their lives." (Craik 168–70)

"It is the unmarried, the solitary, who are most prone to that sort of “sentimental” friendship with their own or the opposite sex, which, though often most noble, unselfish, and true, is in some forms ludicrous, in others dangerous. For two women, past earliest girlhood, to be completely absorbed in one another, and make public demonstration of the fact, by caresses or quarrels, is so repugnant to common sense, that where it ceases to be silly it becomes actually wrong. But to see two women, whom Providence has denied nearer ties, by a wise substitution making the best of fate, loving, sustaining, and comforting one another, with a tenderness often closer than that of sisters, because it has all the novelty of election which belongs to the conjugal tie itself — this, I say, is an honourable and lovely sight." (Craik 174–75)

"Yet they mean no harm ; are often under the delusion that they both mean and do a great deal of good, take a benevolent watch over their fellow-creatures, and so forth. They would not say an untrue word, or do an unkind action —not they ! The most barefaced slanderer always tells her story with a good motive, or thinks she does; begins with a harmless "bit of gossip," just to pass the time away —the time which hangs so heavy ! and ends by becoming the most arrant and mischievous tale-bearer under the sun." (Craik 190)

"Personal interests, personal attachments, personal prejudices, are, whether we own it or not, the ruling bias of us women : it is better to own it at once, govern, connect, and modify it, than to deny it in name, and betray it in every circumstance of our lives. … It is the women—always the women—who poke about with undefended farthing candles in the choke-damp passages of this dangerous world ; who put their feeble ignorant hands to the Archimedean lever that, slight as it seems, can shake society to its lowest foundations." (Craik 196–97)

"it is the lamentable fact, that whether from a superabundance of the imaginative faculty, carelessness of phrase, or a readiness to jump at conclusions, and represent facts not as they are but as they appear to the representors, very few women are absolutely and invariably veracious. Men lie wilfully, deliberately, on principle, as it were ; but women quite involuntarily. Nay, they would start with horror from the bare thought of such a thing. They love truth in their hearts, and yet—and yet—they are constantly giving to things a slight colouring cast by their own individuality; twisting facts a little, a very little, according as their tastes, affections, or convenience indicate: never perhaps telling a direct lie, but merely a deformed or prevaricated truth." (Craik 198–99)

"And this makes the fatal danger of gossip. If all people spoke the absolute truth about their neighbours, or held their tongues, which is always a possible alternative, it would not so much matter. At the worst, there would be a few periodical social thunder-storms, and then the air would be clear. But the generality of people do not speak the truth: they speak what they see, or think, or believe, or wish." (Craik 199)

"The next grand source of gossip —and this, too, curiously indicates how true must be the instinct of womanhood, even in its lowest forms so evidently a corruption from the highest—is love, and with or without that preliminary, matrimony. What on earth should we do if we had no matches to make, or mar; no "unfortunate attachments '' to shake our heads over; no flirtations to speculate about and comment upon with knowing smiles; no engagements "on” or “off” to speak our minds about, nosing out every little circumstance, and ferreting our game to their very hole, as if all their affairs, their hopes, trials, faults, or wrongs, were being transacted for our own private and peculiar entertainment ! Of all forms of gossip—I speak of mere gossip, as distinguished from the carrion-crow and dunghillfly system of scandal-mongering—this tittle-tattle about love-affairs is the most general, the most odious, and the most dangerous. Every one of us must have known within our own experience many an instance of dawning loves checked, unhappy loves made cruelly public, happy loves embittered, warm, honest loves turned cold, by this horrible system of gossiping about young or unmarried people" (Craik 206–07)

"First, let every one of us cultivate, in every word that issues from her mouth, absolute truth. I say cultivate, because to very few people—as may be noticed of most young children—does truth, this rigid, literal veracity, come by nature. To many, even who love it and prize it dearly in others, it comes only after the self-control, watchfulness, and bitter experience of years. Let no one conscious of needing this care be afraid to begin it from the very beginning ; or in her daily life and conversation fear to confess : 'Stay, I said a little more than I meant'—'I think I was not quite correct about such a thing'" (Craik 213)

"Such a revolution is, I doubt, quite hopeless on this side Paradise. But every woman has it in her power personally to withstand the spread of this great plague of tongues, since it lies within her own volition what she will do with her own" (Craik 214)