"Housekeeping in Rome," Charleston Daily News, Dec 25, 1869

Dublin Core

Title

"Housekeeping in Rome," Charleston Daily News, Dec 25, 1869

Subject

Brewster, Anne Hampton, 1818-1892

Italy--Rome

Travel Reports

Finances

Gender Norms

Social Critique

Philadelphia Bulletin

Citation of Different Periodical / Reprint

Description

Originally published in the Philadelphia Bulletin, Brewster writes about how to live comfortably in Rome, differentiating between more and less affluent people. The article gives a graphic "short sketch of life in Rome" and reads like a guide to an affordable life in the 'Eternal City.'

Brewster illustrates differences in daily routines, housing conditions, and expenses between life in the United States and life in Italy. She also advises her readers where to buy items for daily use and where to eat.

Brewster illustrates differences in daily routines, housing conditions, and expenses between life in the United States and life in Italy. She also advises her readers where to buy items for daily use and where to eat.

Credit

Creator

Brewster, Anne Hampton, 1818-1892

Source

Publisher

Cathcart, McMillan & Morton

Date

1869-12-25

Type

Reference

Article Item Type Metadata

Text

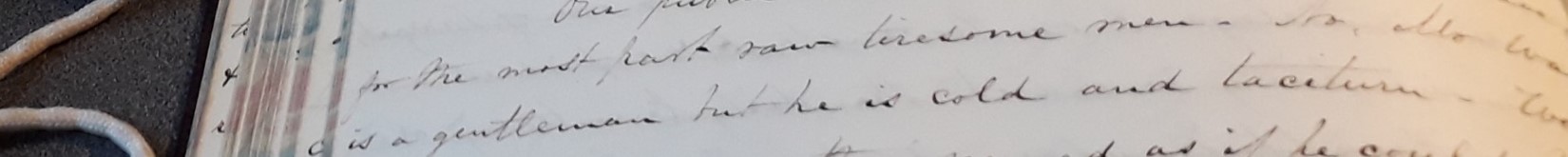

HOUSEKEEPING IN ROME

How Americans Live at a Cheap Rate in Rome.

Anne Brewster writes from Rome to the Philadelphia Bulletin: The luxurious Americans with their heavy, cumbersome machinery of housekeeping, have no idea of the true philosophy of that sort of business as it is understood by the Southern European. It is all useless for our dear country people to come to Rome and sigh after the seventeen kinds of hot bread, the delicious oysters and terrapins, the whiskey that "never hurt anybody," and declare that there is no place like an American home; then return, the men to their down-town luncheon, the women to endless spiritual scuffles with Bridget or Gretchen, Patrick or Fritz--to enormous bills for food they never eat, to all the endless perquisites of the old machine, which, like the old time family couch, ought to be broken in bits-- and expect us, "who have been there" and gone through with the whole heart-breaking business, to agree with them.

Let me give you a short sketch of life in Rome, and you will not wonder that those of our dear countrywomen who have seen und enjoyed it to perfection, pine for the "flesh-pots of Egypt." In the first place, we rent an apartment. They are of various sizes and prices, to suit all tastes and purposes. The rooms are, with few exceptions, on one floor. An apartment, for an ordinary family consists of a salon or drawing-room, parlor, dining-room, three or more bed-rooms, a kitchen and one or two servant's rooms, and sometimes a billiard-room and ball-room. There are few rented apartments in Rome where large dances are allowed, for the buildings are old and insecure. A dancing-hall is only safe on the piano nobile, which, in most palaces, is reserved for the use of the proprietor. Only carpet dances can be enjoyed, and even those are risky. I was at a matinee last spring in the Palazzo Odescalchi, when the ball-room was thrown open, and a dance for the young people started. There were but two or three quadrilles on the floor, and yet I saw the door- hangings and curtains of the adjoining salon sway to and fro quite alarmingly.

There are similar apartments to accommodate one, two or three persons. These are usually suites of rooms which are rented unfurnished of proprietors, by persons with small capital; sometimes working people, wives of petty tradesmen. They invest their little gains in furniture, divide their apartments off, and underlet them. Service is supplied, and sometimes meals. Many who rent these small apartments of these persons have their meals sent in from a trattoria, or eating-house. If you have a comfortable purse, you can order your meals from Nazzari's or Spillmann's--those delightful Roman restaurants-you may find trattoria fare palatable. But my advice is to secure an apartment where the pradona [sic]--as your landlady is called--will serve you with your three meals; that is, if you are only one or two, have moderate means, and come to Rome to study and see everything. Your landlady will render you a daily account, and you will be amused with the precision of the items.

"Filetto, eight soldi a slice"--that is, breast of turkey, which is sold in that way uncooked, and you can have as many slices as your appetite requires "+++, ten soldi"--a delicious dish made of the livers and hearts of chickens, with rice and curry sauce. Oso, ten cents, which is the bone and meat for the daily soup. Pane--bread--five cents a loaf. Butter, from three to ten cents a pat, just enough to last the day. Cream, from two to ten cents--as much as you want ; and so on--every vegetable, meat, fruit, &c., mentioned with its price. Thus you can daily order your next day's meals according to your taste and purse. If a visitor comes in suddenly to whom you wish to be hospitable, you can send to Mmes. Nazzari's or Spillmann's, for one or two fine dishes, and your table will be sumptuous. Then there are plenty of delicious little potted delicacies, pâté de foie, anchovy paste, &c., which are extremely nice to have on hand tor emergencies, or for your own occasional daintiness, when the natural depravity of your stomach makes you quarrel with your padrona's paradisaical providings. By managing in this way, four or five francs a day. (equal to eighty cents or one dollar in gold,) will give you an excellent table-three meals for one person ; while one good trattoria dinner alone, from Nazzari's or Spillmann's, costs six francs for one person ; then comes in added the expense of breakfast and luncheon.

The great charm of this Roman mode of life, when managed in the Roman fashion, is that you can regulate daily, to a penny, your expenses ; and when you dine out, or when your duties out-doors make it more convenient for you to dine at a restaurant, your expenses are not going on at home. Even if you have a kitchen and servants, their table is not yours. You pay them certain wages, and then allow them daily so much money for their own food, which they spend as they please. You have no responsibilty. It is no meanness to have a fine roast, or any nice dish set aside for your own future use. The servants here are so experienced in their science of culinary economy, also, that they seem to know to a slice how many potatoes to cook for one person, and so on with every article of food.

True, wealthy Americans come to Rome and bring with them home habits. The surveillance of house accounts has hanging around it wretched memories of home wrestlings and griefs, so the mistresses omit this very necessary duty. They order more food than is needed, or can be used at their own table, and think, according to the law and gospel, their own kitchen gods and goddesses taught them with bitter suffering, that it is a contemptible parsimony to have the cold meats kept for further use at their own meals, and send them all into the kitchen. The Italian servants, unaccustomed to this "barbaric generosity," become speedily demoralized, and a system of thieving begins which is endless.

But those of us who have small means and little leisure, live differently; we copy the natives, adding the while a few liberalities of American life, and the comfort and peace of mind that results is delightful. Everything about housekeeping in Rome can be under your own eye, and is arranged to give you the smallest amount of trouble. Wood, for example, you purchase by the charette, or load, which is a little over half a cord, and order it, strange to say, at your grocer's! To be sure, the Romans of comfortable means get their fuel in another way, from their own lands or from farmers, but the stranger will do better to go to Madame Fichelli's, on the Piazza di Spagna, or some well known shop of the kind. The wood is sent, nicely dried, cut small, up to your apartment door, and stored away, sometimes in clothes presses or in the recesses of an ante-chamber, and hidden very often by a beautiful curtain or piece of rich old tapestry ; for economy of space is also another branch of this "great virtue for women and vice for men," as old John Adams used to define economy. Poor man! What would the good old '76 square-toes say if he could come to life in these days of women's rights to all men's vices and "more too." Verily, "Nous avons changé tout cela!"

Provenance

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026994/1869-12-25/ed-2/seq-7/. Accessed 6 Oct 2021.

Length (range)

500-1500

Social Bookmarking

Geolocation

Collection

Citation

Brewster, Anne Hampton, 1818-1892, “"Housekeeping in Rome," Charleston Daily News, Dec 25, 1869,” Archival Gossip Collection, accessed April 26, 2024, https://www.archivalgossip.com/collection/items/show/869.