Conference Paper for Digital Humanities and Gender History (Feb 5, 2021) organized by Prof. Dr. Mettele, Pia Marzell, and Martin Prell

[Katrin] Introduction: Who We Are and What We Are Doing

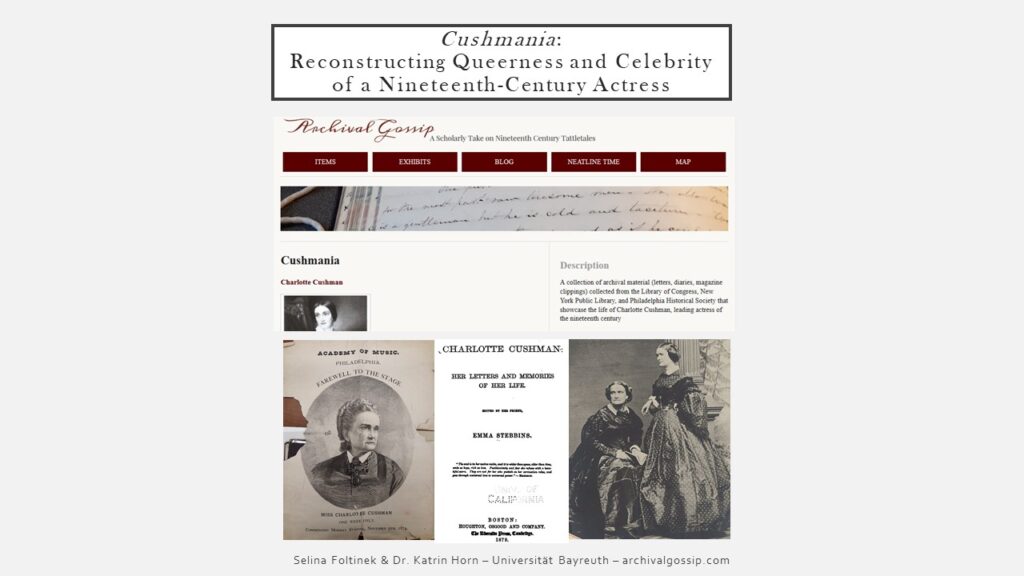

Thank you to the organizers for having us today and thank you to everyone for your interest in “Cushmania: Reconstructing Queerness and Celebrity of a Nineteenth-Century Actress.”

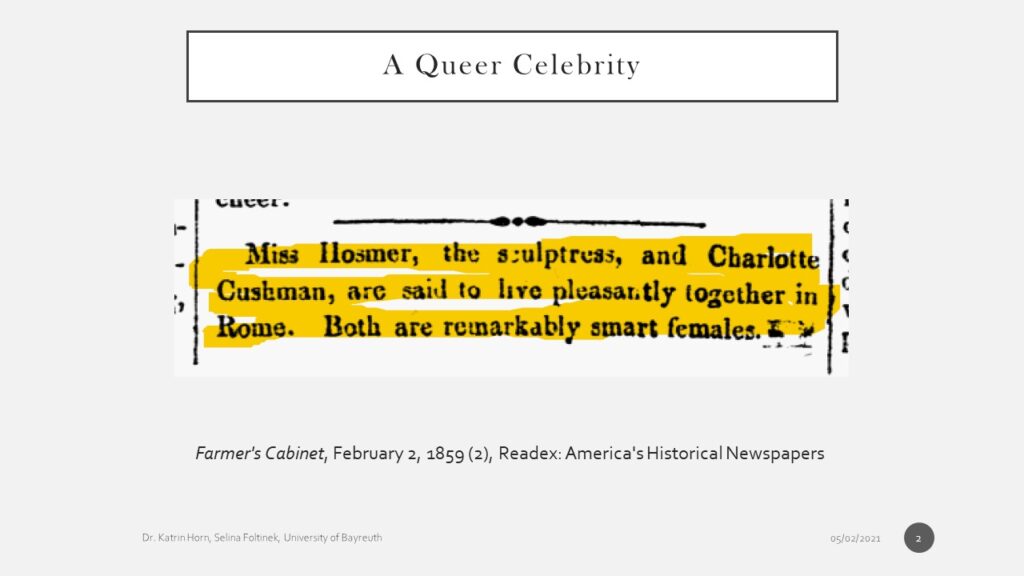

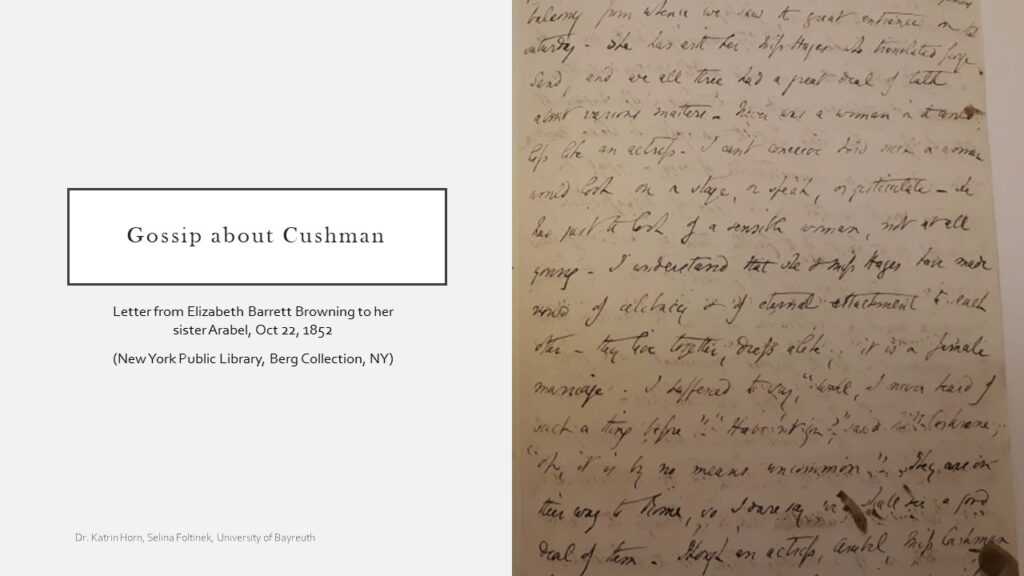

Almost exactly 162 years ago to this day, the US American public learned that Miss Hosmer and Miss Cushman lived happily together in Rome. Now you are forgiven if you don’t recognize either of these names. I guarantee you, however, had you lived back then, you would have known Charlotte Cushman. Cushman was one of the most famous, most talked about women of her time – which you probably can guess from this little snippet, the same way that you already get a hint of her queerness.

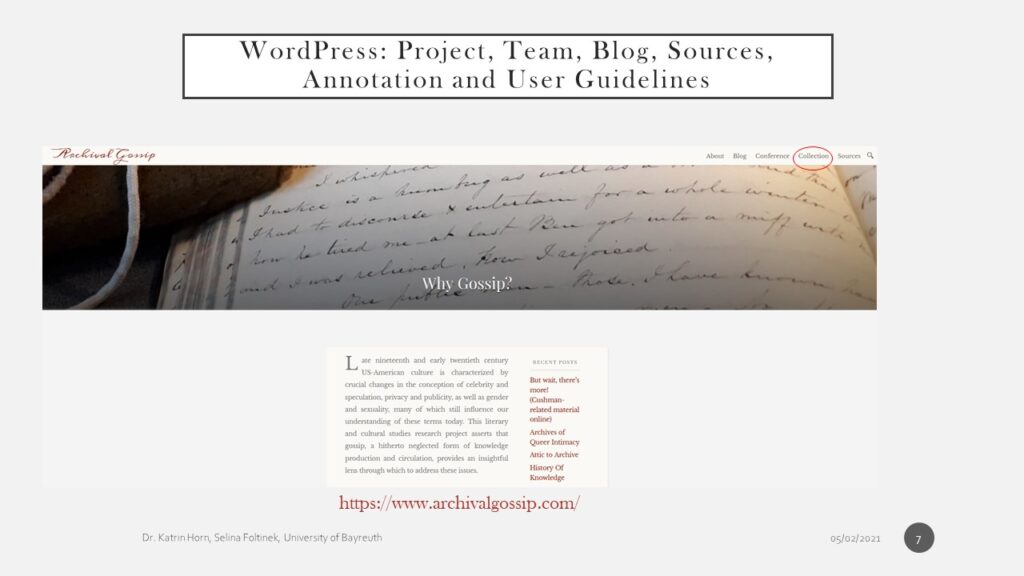

Today, we (Selina and me, who shoulder this project together) would like to present parts of our ongoing research project entitled “Economy and Epistemology of Gossip in Nineteenth-Century US-American Culture,” for which we have built the website archivalgossip.com – which includes, among others, the collection Cushmania. Cushmania is an online database documenting the public reception and private life writing of actress Charlotte Cushman (1816-1876) via material collated from various US-American libraries and archives.

Cushmania to us is several things:

- it’s a work in progress

- it is the central database for our research data – letters, diary entries, newspaper articles, book excerpts, images – for which a ‘traditional’ desktop folder structure proved simply impossible

- it’s a key visualization tool to make sense of temporary, spatial, and personal networks and developments

- and it is our offer to a public interested in the aspects (and people) of nineteenth century history not always showcased by archival institutions: Cushman was, after all, a woman, an actress, an expatriate, and queer.

To give you an idea of how Cushmania and the reconstruction of celebrity and queerness fits into our larger project on gossip, I will begin by talking about some of our core research questions. This part will contextualize the project within the fields of American Studies and Gender History.

In the second part of the presentation, Selina introduces our website and database to give you an idea of how we fit into Digital Humanities. And then, I’ll take over shortly to sum up and lead into the Q&A.

[Katrin] The Project: Content and Research Interests

Our project overall investigates the uses and value of gossip in late nineteenth century US American literature and culture. As “a discourse that negates and conflates the dialectics of inside and outside in its movement between the private and the public realms” (Bastin 24), an “alternative discourse to that of public life” (Spacks 46) and an “informational black market” (Kapferer 9), we claim that a focus on gossip offers new insights into changing understandings of privacy (e.g. the right to privacy), and public sphere (and the role of celebrities/high society). In all the material we rely on – from novels, to gossip magazines, to diaries and letters – we focus on women. We do this, because a) their often precarious public standing makes for particularly intriguing gossip scenarios, and b) we want to show how women’s public role has historically been undervalued.

Cushman quickly emerged as the perfect case study for thinking through women’s participation in the public sphere and the role of gossip (as both source of information and object of study in its own right). Despite public and private attacks on her gender expression in private and during stage performances (in breeches roles), Cushman managed to not only dominate the Anglophone theatrical scene for several decades, but also to position herself as a model American citizen and admired female artist. As such: there is a wealth of public writing about her. Thankfully, there is also a wealth of private correspondence today, only accessible because Cushman and her circle of friends and acquaintances were ‘historically important’ (as many of you will know: archival material on marginalized people, such as women and LGBTQI people, is often rare).

Archival Research to DH

This “traditional” archival research is then also the reason for why we “went digital” and ultimately why we are here: As already indicated, gossip relies on networks. Hence, we needed to take into consideration Cushman’s own writing, but also the letters addressed to her, and often also letters and diary entries about her. To this end, we’ve collected manuscripts from over ten US American archives. In addition to this “private side,” we also wanted to understand, what was publically written about the actress (and her relationships): hence, we’ve additionally collected a large number of biographies and articles.

Currently, we work with about 20GB of primary material from various sources and in various formats. To be able to actually work with that we wanted to find a solution that would allow us to store, sort, annotate, and visualize our data. A database seemed to do the trick. The database solution that eventually allowed us to include scholarly metadata and upload our data without recourse to Google, for example (which our funding institution would not have allowed) was Omeka. In the words of N. Katharine Hayles we therefore started from a “assimilative strategy” (that’d be “extend[ing] existing scholarship into the digital realm) (50).

Initally, we were mostly interested in the database as a “tool” for our “traditional research.” Now, the project has evolved quite a bit, and our digital tools have actually begun to shape the research – and we think about extending the digital aspect of our work even further. But before we get to those “lofty goals,” Selina will first explain what Cushmania actually is and does.

[Selina] The Project: CMS, Database, and Research Tool

With our digital collection, we seek to exhibit the biographical discourses surrounding Cushman during her lifetime, including her own writing, newspaper articles, diaries and letters by friends and acquaintances, as well as contemporary (auto)biographies. Our website addresses both ‘professional users’ such as researchers who are interested in our digital objects, metadata, or archival research as well as non-professional users who search for more information about Charlotte Cushman, other 19th century actors like Macready or Edwin Booth, female sculptors like Harriet Hosmer or Emma Stebbins, famous editors like James Thomas Fields, etc.

Our journey started in April 2019 and as of now we mainly work with three different tools or ‘digital spaces’

- our own WordPress website where we introduce ourselves, publish blog posts about issues related to archival research and digital humanities, provide a list of archives, Annotation and User Guidelines, etc.

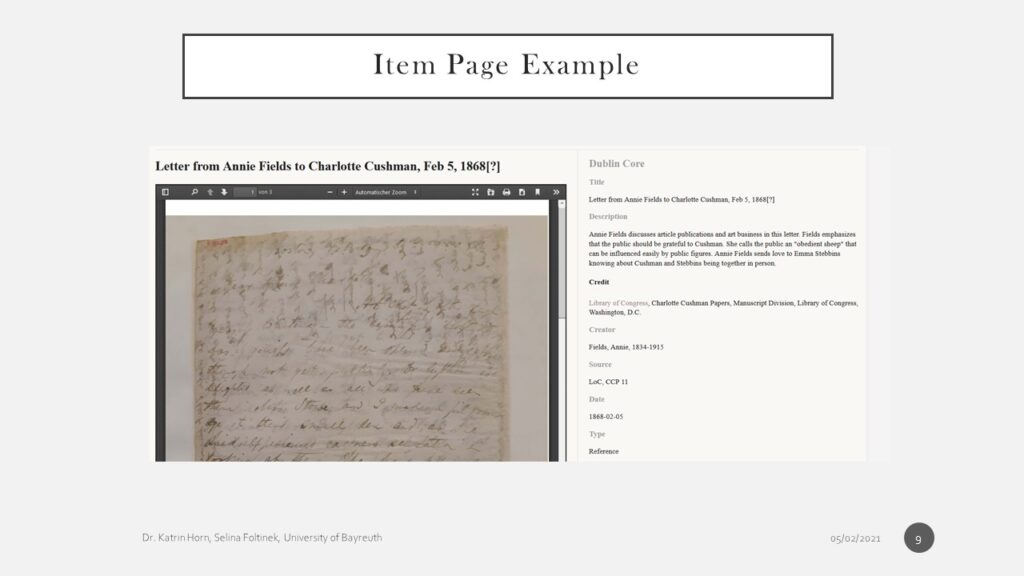

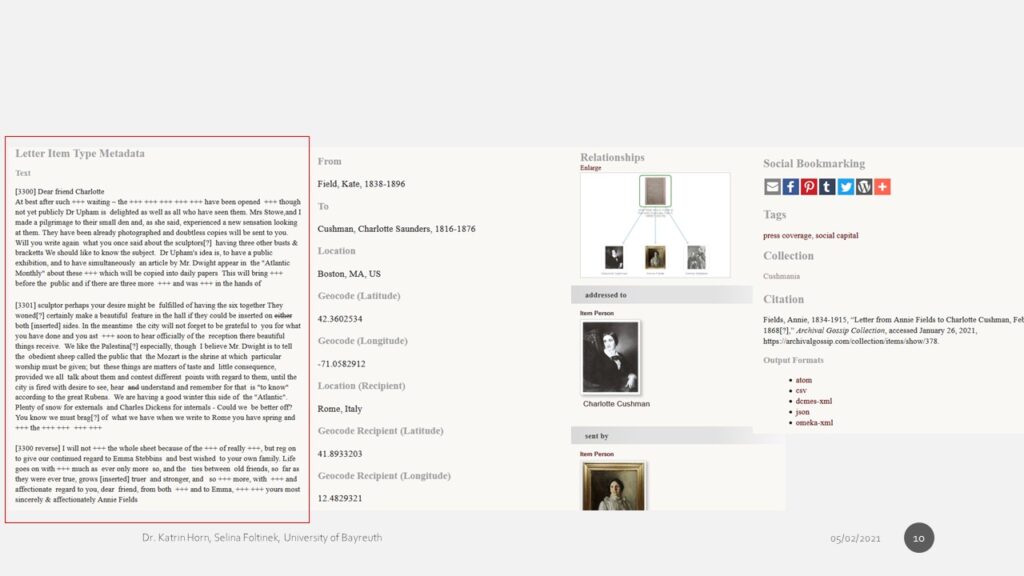

- from the WordPress website, users can access Omeka, our main tool for managing our archival documents (it is a web publishing platform which we use as our Content Management System), where we store “digital surrogates of originally analog artefacts” (Schmidt 125); I also have an item page example:

- images or pdf on the left

- Dublin Core Standard for basic metadata +

- followed by Item Type Metadata to specify metadata for specific types of documents: letters (location sender and recipient), annotation notes, provenance (the original document might be taken from LoC, but we are using transcripts from Colorado College, for instance; Seward letters from website), link related items, offer different output formats

–> for the transcriptions in the ‘text’ field

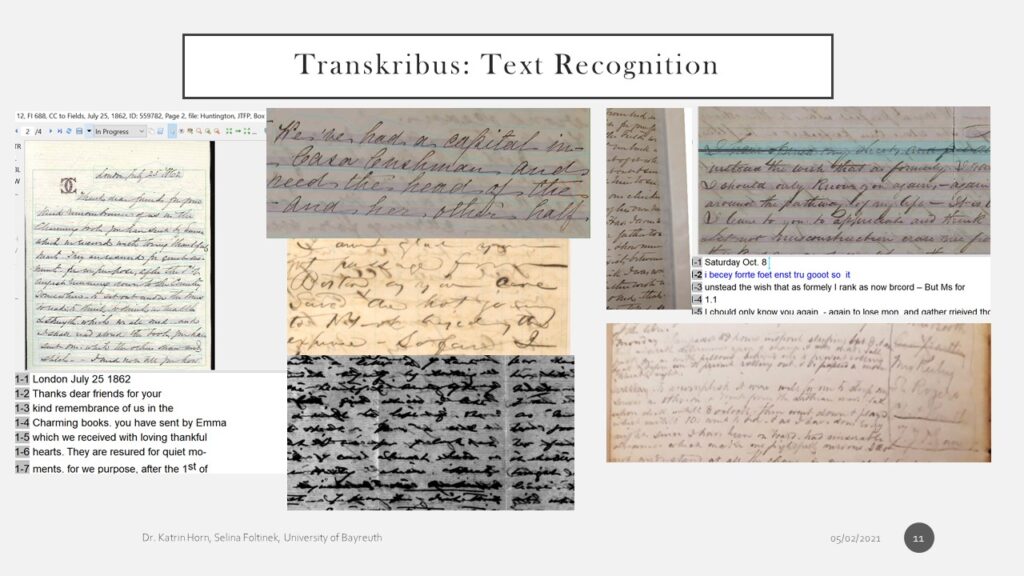

- we use Transkribus to transcribe letters and further handwritten accounts from the 19th and 20th century to include full text transcriptions for the item pages

Initially, we transcribed documents without any technical support. In April 2020, we then trained our own model based on our transcriptions of more than 180 pages. This model is constantly improved and modified. Transkribus is an excellent tool that helps with line-by-line and automatic transcriptions. Currently, the CER (Character Error Rate) for our 19th century model is slightly above 9%. The CER for our 20th century model is slightly above 4%. Why is the CER for the documents from 19th century so much higher? Well, because we have many different styles of handwriting as you can see on the slide:

left column: Cushman (with a particularly clear type of handwriting in this case; she often wrote letters when she was in distress, tired, or ill)

in the middle section: Kate Field (a journalist and friend of Cushman), Wayman Crow (the father of one of Cushman’s love interests), a microfilm of a letter by sculptor Harriet Hosmer,

in the right column: you can see one of my favorite documents where someone put tape on letters to make the letters stick to the paper page, some documents are damaged, or hard to read (even Emma Stebbins, Cushman’s life-long partner, had trouble reading Cushman’s life writing documents while preparing a Cushman memoir), you can see Cushman’s diary entry written in pencil

Our initial goals were to find tools to help us

- to collect and organize our archival material (so far: 326 letters, 544 items)

- to create and curate digital objects: i.e. build online exhibits according to research questions

- to transcribe and annotate handwritten archival documents

- to tell a story (focus on gossip-related material)

We work on what Susan Brown (2015) calls that the weaving together of narrative and database (62–63).

- the Omeka site allows for different types of visualization [Relationships, Exhibits, Item Page, Timeline, Map], which then again help us with organizing and making sense of the documents

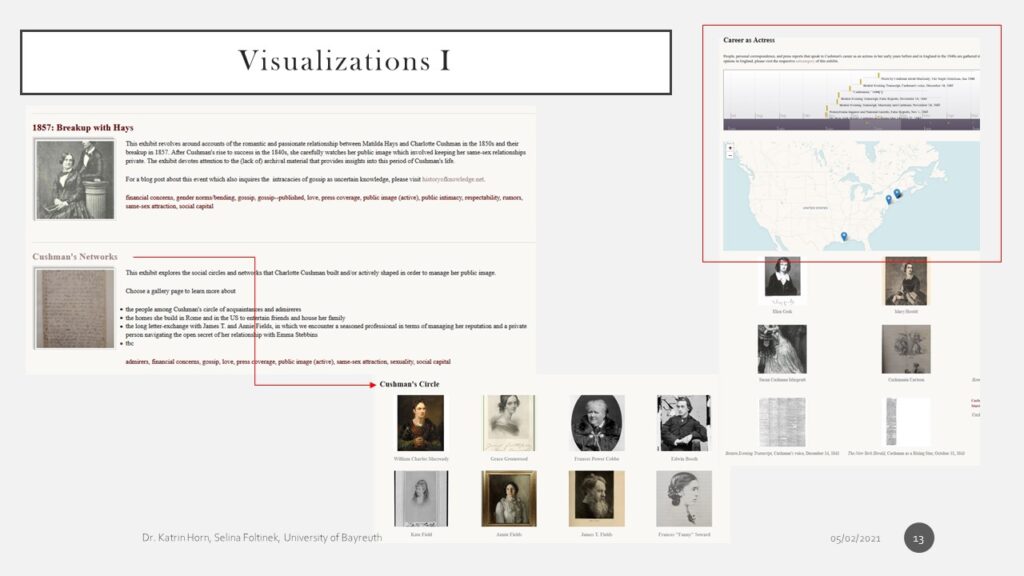

- speaking of visualization, I have three slides to illustrate this part [Visualizations I]

- we are building exhibits to assign items to different research questions: here you can see two examples, these exhibits than have subcategories or topic-specific pages: e.g. Cushman’s circles that displays all historical agents that were somehow networking with Cushman; another exhibit: Career as Actress shows further visualizations: timelines and maps that add to the gallery of items displayed below

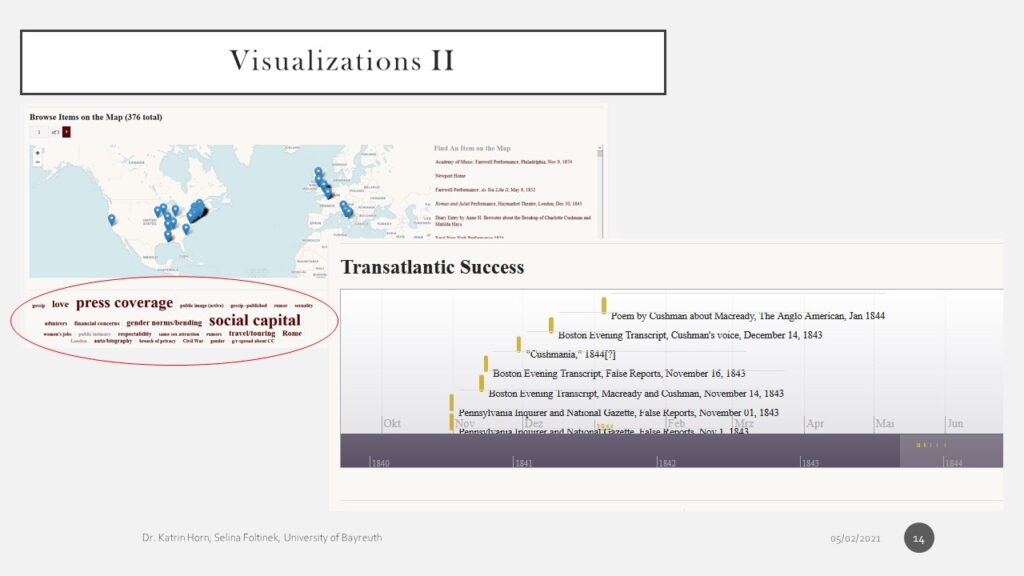

- [Visualizations II]

- mapping the origins of archival documents shows us where a letter was written or an article was published (and hence we would get an idea of where Cushman was talked about or where she was writing from)

- we are providing timelines for specific exhibits and research questions to give chronological overviews and help the users and us orientate

- we are using tags to help both users and us to navigate and search for specific topic-related items; the tags do also relate certain items with one another whose connections may not be visible in a list of documents

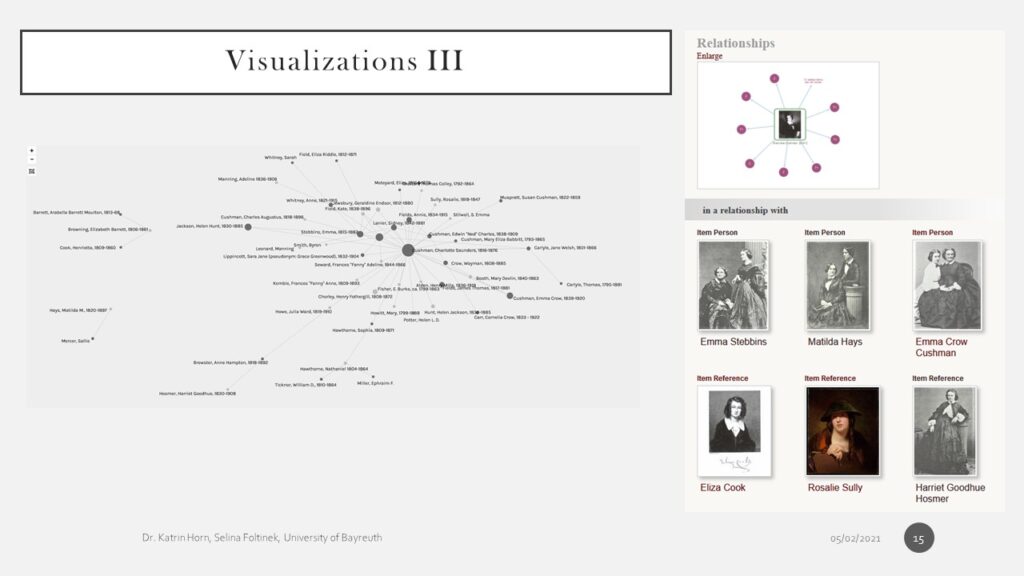

- [Visualizations III]

- the AvantRelationship plugin lets us define relationship types: Each Item is defined as Reference (documents), Person, Event (that is the item type in Dublin Core). We can define relationships between items such as a letter “is addressed to” or “Is critical of”

This plugin actually forced us “to make explicit many assumptions often left implicit in our work” in the humanities (Drucker 85)

- use our collected metadata to feed other DH tools such as Palladio to provoke new insights, ask new questions, keep track of the material we have available; the bigger the nodes the more letters (in this particular case) were sent to or received by the respective person

–> Palladio thus provides an overview of all historical agents

- BUT and this leads me to future aspirations or ideas with DH potential

- we are not doing network analysis, no nuances of nodes and edges as proportionate to tightness, duration of relationship

–> what our visualizations lack is giving an overview of large quantities of data to show how different networks of people are linked (e.g. male editors and protolesbian communities)

- we also do not have in-text mark-up yet: our current stage of digitizing is not yet completed; atm only simple html tags for deleted or italicized words, page breaks, etc.

- but no machine-based text analysis yet

- we keep thinking of digital tools/methods to explore gossip structures: for instance, certain phrases such as “it is said” or “people say” often introduce gossip: so, marking certain phrases as discourse markers of gossip could provide an overview of how and when gossip played a role in letters, articles, and diary entries; we are open to suggestions that help us identify gossip structures, compare rhetoric, mark certain passages as reputation management/public gossip/etc.

- for the time being, we use our much simpler version which is digital tagging with Omeka tags (that are however not tied to specific paragraphs, sentences, etc. but to items) = it is, however, tool to help us read closely, a method that is also called scalable reading because it combines distant and close reading

[Katrin] Conclusion: Reconstructing Queerness and Celebrity of a Nineteenth-Century Actress

To add to Selina’s thoughts on what has and hasn’t worked for us on a technological level, I would like to shortly connect all of this back to the project at large. With regard to archival research, Maryanne Dever has claimed that

The challenge […] becomes one of how to read and work with these fragments, given that, as researchers, ‘we are generally dismayed by the gaps that fragments expose, and try to fill them’.”

(Dever)

In working with and around fragments and the gaps between them our database is certainly more forgiving than any argument or narrative we would usually present as a result of scholarly research. Also, in trying to make sense of just how famous Charlotte Cushman was, the database’s ability to combine various media (from posters, to comics, to reviews, articles, and biographies) has been invaluable. We are also enjoying the opportunity of adding female and LGBTQI lives and voices to the discussion of historically important moments (in Cushman’s case: Civil War, expatriate community abroad, institutionalization of theater, etc).

There are, however, also ongoing struggles that result from our reliance on digital tools – namely when it comes to queerness rather than celebrity. The discrepancy between these two defining aspects of Cushman’s life – the public and the private, the idealized and the deviant – is what drew me to her originally. But it’s also that which causes the most friction.

DH scholars such as Bonnie Ruberg have criticized the binary logic of digital environments: male/female or married/single (Ruberg et al. 109-110). How could our database, for example, reflect the historical nuances and developments of relationship status: By today’s standard, Cushman could be considered “married” to Emma Stebbins – legally, however, there was not such status available to her. Similarly, the use of the “relationship plugin” triggered some extensive discussions about the differences between relationships, affairs, flirtations …. How do we define a relationship we only know partially and through biased accounts so that a simple plugin can make sense of it? These are, for us ongoing questions.

On the other hand, queerness has a certain affinity to our format of presenting what we know about Cushman, insofar as her private life (just like her public success) was networked to a high degree. Cushman and the women in her circle therefore resist what Susan Brown calls an “isolated biography.” And lastly, with our specific interest in the intimate knowledge of gossip, we’d consider the data collected in Cushmania an effort that reflects “the queer potential of archiving itself as a practice that challenges concise, monolithic, and often hegemonic interpretations of knowledge” (Ruberg et al. 111). Our goal is to illuminate how Cushman, her social network, and the wider public shaped and perceived her reputation in ways which reconciled the open secret of her sexuality with her international celebrity. We are, in other works, interested in how knowledge travels and is concealed, how networks – of knowledge, of intimacy, of care, of profit – have shaped and been shaped by Cushman’s queerness and celebrity. For all these questions, Cushmania is instrumental.

Thank you for your attention!

(authors: Katrin Horn, Selina Foltinek)

Works Cited

Adkins, Karen C. “The Real Dirt: Gossip and Feminist Epistemology.” Social Epistemology, vol. 16, no. 3, 2002, pp. 215–32.

Bastin, Giselle. “Pandora’s Voice-Box: How Woman Became the ‘Gossip Girl’.” Women and Language: Essays on Gendered Communication Across Media, edited by Melissa Ames and Sarah Himsel Burcon, McFarland, 2011, pp. 17–29.

Brown, Susan. “Networking Feminist Literary History: Recovering Eliza Meteyard’s Web.” Virtual Victorians: Networks, Connections, Technologies, edited by Veronica Alfano and Andrew Stauffer, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 57–82.

Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis. U of Chicago P, 2012.

Kapferer, Jean-Noël. Rumors: Uses, Interpretations, and Images. Transaction, 1990.

Ruberg, Bonnie, et al. “Toward a Queer Digital Humanities.” Bodies of Information: Intersectional Feminism and the Digital Humanities, edited by Elizabeth Losh and Jacqueline Wernimont, U of Minnesota P, 2019, pp. 108–28.

Schmidt, Desmond. “The Role of Markup in the Digital Humanities.” Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung, vol. 37, no. 3, 2012, pp. 125–46.

Spacks, Patricia Meyer. Gossip: A Celebration and Defences of the Art of ‘Idle Talk’; a Brilliant Exploration of Its Role in Literature (Novels, Memoirs, Letters, Journals) as Well as in Life. Alfred A. Knopf, 1985.

Great work archivalgossip! To added to your archive are Emma Stebbins letters from the Henry A. Clark Sr. collection.

Thanks for reading – and for the tip! I’ve browsed you website, but couldn’t find any letter by Stebbins. Is there anyway to find out more about them?