Today is the day that I finally guide you through my favorite items of our Cushmania and Gossip Columns and Columnists collections. After more than three years of transcribing and annotating archival sources, I selected a mix of items that are not necessarily related, linked, nor do they cover the same topics. Instead, they are the ones that stick with me after I shut down my laptop. They are the anecdotes I tell other people about who are not interested in a specific topic covered by our collections but who inquire more generally about what there is in ArchivalGossip.com.

Harriet Hosmer in Rome: “Such a Gem”

The one person that I mention the most in chit-chat is Harriet Hosmer. Hosmer (“Hatty”/ “Hattie”) was a nineteenth-century US-American sculptor who became widely known as part of the expatriate circle of US-American artists in Rome. Among Hosmer’s long-term female partners were Lady Ashburton and Emma Crow’s sister Cornelia Carr. She was friends with Wayman Crow, and lived with Charlotte Cushman and Emma Stebbins in the Via Gregoriana, Rome, in the 1860s. In that decade, she also had to defend herself against slander when several male artists challenged her ability to create her sculptures on her own as a woman. As a response to that sexism, Hosmer published a witty, four-pages poem, “The Doleful Ditty of the Roman Caffe Greco” (New York Evening Post 1864). Not only Charlotte Cushman (who is the center of attention in our Cushmania collection) or journalist Grace Greenwood (who features prominently in the Gossip Columns and Columnists collection) supported the sculptor, Lydia Maria Child also published the following account to defend Hosmer’s profession and gender performance:

The energy, vivaciousness and directness of this young lady’s character attracted attention even in childhood. Society, as it is called, – that is, the mass of humans, who are never alive in real earnest, but congratulate themselves, and each other, upon being mere stereotyped formulas of gentility or propriety, – looked doubtingly upon her, and said, ‘she is so peculiar!’ ‘She is so eccentric!’ Occassionally, I heard such remarks; and being thankful to God whenever a woman dares to be individual, I also observed her. I was curious to ascertain what was the nature of the pecularities that made women suspect Achilles was among them, betraying his disguise by unskilful use of his skirts; and I soon became convinced that the imputed eccentricity was merely the natural expression of a soul very much alive and earnest in its work. […] I think genuine lovers of the beautiful will henceforth never doubt that Miss Hosmer has a genius for sculpture. I rejoice that such a gem has been added to the arts. Especially do I rejoice that such a poetical conception of the subject came from a woman’s soul, and that such finished workmanship was done by a woman’s hand.

“Miss Harriet Hosmer,” Liberator, Nov 20, 1857

Other contemporary, widely distributed sources similarly reported on Hosmer’s gender-bending behavior:

Miss Hosmer is often seen in public here in Rome, at times driving a handsome carriage and span rapidly along the streets, at times on horseback, making her way (in which latter capacity she excels,) to the meet of the foxhounds on the Campagna. The pack this year is good, the sport fair and the amusement very fashionable. Miss Hosmer is an expert rider, and both she and Miss Cushman are often seen going at a furious pace over walls, fences and ditches close upon the heels of reynard. Each of these ladies has a strong and tireless energy, and a muscular physique which many men may well envy. They are gifted with wonderful endurance, which the latter has often had occasion to display upon the stage, and with which many of your readers are familiar. Both are thoroughly American and patriotic, yet of strong and impressive individuality that brings them out in striking contrast with the rest of society in Rome.

“Rome – Foreign Correspondence of the Boston Post,” Boston Post, February 23, 1867

Ever since I read this item, I picture Hosmer racing through Rome’s streets. She is the one in the riding gown, always on the run, the center of attention. Cushman described Hosmer once as a “clever selfish little monkey” (Letter from Charlotte Cushman to Emma Crow, March 13, 1862) and disapproved of Hosmer’s work-life-balance:

Miss Stebbins says Hattie is out at 3 parties of a night & not home until the small hours of the morning. This. to a person who has to rise at 7. to get to her work at which she stands for several hours. & then rides “hard, hard” for 2 1/2 hours in the afternoon is quite sufficent to give her pains in her head & cold feet[?]! She is an immense favourite in society & cannot forego the charm & excitement which it contains. next year I hope to keep her a little within bounds. but no human being has any controul [sic] over her!

Letter from Charlotte Cushman to Emma Crow, Apr 27, 1858

Such characterizations of Hosmer were quite common in public as well as more private accounts. The Liberator article above was reprinted several times, and is quoted by Grace Greenwood as well. Greenwood, the journalist, was a member of Cushman’s circle of US-American friends just like Hosmer. Together with Hosmer and Cushman, Greenwood came to Rome at the beginning of the 1850s. She comments on the Liberator article:

She had queer old ways and notions; she never played with dolls, but I’ve heard her folks tell how, on bakin’ days, she would sit in her little rockin’ chair with a plate in her lap covered with bits of dough, and out of them she’d make little figures of animals and human creaturs [sic], as natural as life […]. […] Her father […] let her run wild among the hills; he horrified all the prudent old ladies in his neighborhood by unring her to sun and storm, and teaching her to ride, drive, hunt, fish, row, skate, and swim. In all out-door exercised she became a proficient, and as a matter of course, grew up strong and vigorous. She is remarkable for her power of endurance, for steadiness of nerve and courage. She is not only the bravest woman I ever met, but I know no man more utterly fearless than she.

“The Education of Our Girls,” Vermont Chronicle, Aug 8, 1868

I was with Miss Hosmer during her first winter in Rome, and that was – ah, me! fifteen years ago. She was then small and slight, singulary vigorous and muscular, a bundle of healthy nerves, energy, and will. The strong head borne with infinite spirit, was crowned with beautiful brown hair, short and curling. The face was fresh and piquant, but of force and character. About her mouth the lines of a strong purpose were hardening already into resolution, fixed and inexorable. Out of her gray eyes shone the steady light of well-assured ambition. Her style of dress was slightly after the masculine order, but in admirable keeping with her chosen work. In manner and conversation she was the farthest possible remove from the conventional fine lady yet neither coarse nor unwomanly. I have, it is true, since heard some startling stories of her manly, independent goings-on, her “tricks and her manners.”

With its resignification of Hosmer’s gender-bending behavior, it is an exemplary piece of writing by a member of Cushman’s transnational circle of women in the public sphere that sought to defend and praise one another to add to their public acknowledgement as successful women (or even geniuses). These women used their (professional and social) networks, their joint (traveling) experiences, and their professions to foster their bonds and become even more successful and widely known. The article circulated Hosmer’s name and contextualized and ‘softened’ the masculinity of her appearance and behavior to a mid-nineteenth-century reader that was potentially critical of her gender-bending attitude. Simultaneously, Greenwood made money with such articles based on her access to these circles of professional women.

Similar to Greenwood, Elizabeth Barrett Browning was impressed by this fierce, successful woman that could take care of herself. The following excerpt is one of my favorite contemporaneous descriptions of the sculptor:

Hatty looked radiant when I saw her. She came in one evening after dining with Pantaleoni, with large sleeves, & lace, & everything pretty. She remains Hatty after all. The night before she had been with Miss Cushman, & returning home at ten was encountered by a man who extended his arms & enquired why, she walked the streets of Rome at so late an hour– It was close to her own door, & she knocked before she spoke. Then turning round she said “You ask my reason for walking so late. This is my reason–” And crash across his face she struck with her iron-pointed umbrella. He turned & fled like a man—I wont [sic] say as Miss Cushman did, like an Italian. So there’s your Hatty for you.

Letter from Elizabeth Barret Browning to Isa Blagden, Dec 12, [1858]

These bits and pieces speak to the public image of the queer women that are the major historical figures in ArchivalGossip.com. They also show how Hosmer, Cushman, and Greenwood belonged to a transnational community of women that made their way into the public sphere relying on one another, making their own money, and defending their independence.

“Electric Shocks of Passion”

In ArchivalGossip.com, you can find many such thoughtful and tender descriptions of women by other women. Repeatedly, Greenwood published letters in which she praised Charlotte Cushman, for instance:

She may exaggerate, but she never be-littles–she may over-pass the idea of the poet, or our own, but she never falls behind it. Her genius is wonderfully strong and individual–full of glowing vitality, palpitating with a rich, vigorous life. Her power in high tragedy has much of regal sway and consciousness–somewhat too much, it may be of arrogance and fierceness at times; but she grasps you, holds you, and conquers you, finally, whether you rebel, or submit at first. She compels your half-bewildered admiration, she commands your awe-struck sympathies, she gives you sudden electric shocks of passion, she storms upon you with all the fire and flood of maddened love, hate, revenge, anguish, and despair. But this is only the night side of the picture–there is another side of sunshine, of glad, golden, Italian sunshine. In scenes of playful tenderness, her voice, her look, her manner, have a most subduing sweetness and a peculiar, child-like charm.

Reprint of Greenwood Letter, Daily American Telegraph, April 12, 1852

Here, Greenwood celebrates one of Cushman’s most contested but also most successful performances, “her splendid representation of Romeo.” In case, you want to know more about this performance and its discussion in the press as well as in private correspondence, refer to our exhibits Transatlantic Success in the 1840s and Public Image of Charlotte Cushman.

What the Squirrel?!

Birds, horses, squirrels in an online archive on gossip? As you have learned above, Cushman and Hosmer were expert riders, and Cushman sometimes had her horses shipped from another country. Frequently, Cushman called her younger lover Emma Crow pet bird. The squirrel story, however, was unexpected, and is totally unrelated to gossip or any research questions around which our exhibits and collections revolve. At the time that I transcribed the respective letter, I was still in my early attempts to decipher the nineteenth-century handwriting of Cushman, her friends, and family. I was quite surprised to find a “squirrel” on the pages of a letter by Charlotte Cushman’s nephew who took care of such an animal that he wrote to his mother about:

I hope […] that you like the squirrel I sent out to Rose & Ida, you must not let them handle it, for although he will not bite, when he runs over them his claws are so sharp that he would scratch pretty hard, he has been a great comfort to me all winter

Letter from Ned Cushman to Susan Muspratt, n.d. [before April, 1857?]forhe has been quite a companionto mefor he would come and sit on my shoulder and look on when I was reading or climb up into my pocket and be up to all kinds of tricks, Henry will take care of him for me I dare say and feed him on nuts

In order to tell that this passage had nothing to do with our research interests, we had to, however, transcribe it first. This example thus also speaks to the time-consuming activity of transcribing handwritten letters that are hard to skim, in particular when I had just started reading all the different nineteenth-century styles of handwriting. Even though such letters may turn out irrelevant to our original research questions, some of them will still stick with us because we remember such unexpected findings and stories. From Ned Cushman, I learned that squirrels were apparently a popular pet in the nineteenth-century United States.

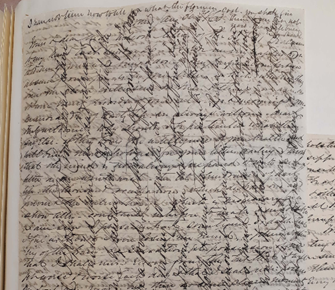

“school myself to live without such love”: Love Letters

All of those people who have ever transcribed or read (about) Cushman’s letters will now ask: Where are the love letters? No worries, I just saved them here for last. I have transcribed hundreds of pages of those lengthy but intriguing letters, most of them I could luckily transcribe with the semi-automatic text recognition tool Transkribus. Most of the letters that are preserved until this very day were sent from Charlotte Cushman to her younger partner Emma Crow, who later married Cushman’s nephew and gave birth to the children that Cushman considered to be theirs. These letters often stretch over more than four pages, and in them, Cushman shares her most intimate thoughts about her life, her work, society, gender norms, love, and her social circles. They are an excellent source for gossip-related themes as well as queer female desire and relationships in the nineteenth century. They are often hard to read because Cushman had so much to say, was stressed, tired, or ill. To give you an idea of how such a letter could look like, check out this one:

Despite her job, social duties, and her health, Cushman always took the time to sit down and write to her lover whom she called “pet bird,” “darling daughter,” and “sweetheart.” Emma Crow shared a long-term partnership with Cushman, although she never lived side-by-side in a home with the actress as did Emma Stebbins, who Cushman called her “wife.” The following letter is an early example of Emma Crow’s and Cushman’s romance. Among the many letters I could cite here, I chose this one as it offers insights into the intricacies of relationship commitments, jealousy, and same-sex love:

if the truth may be told she [Emma Stebbins] does not like me to love you too much. she is very very dependent on your darling. & if she thought or dreamed how I love you. it would go near to kill her I believe. This makes me very very unhappy at times. & I wonder whether I ought not to school myself to live without such love. But ah how hard it would be now. now that I have tasted the sweets of such communion as is given[?] to few to know. my darling love do you remember our last night in Paris. ah what delirium is in the memory & how every nerve in me thrills[?] as I look back & feel you in my arms held to my heart so closely. so entirely mine in every sense as I was yours. ah it is very sweet. very precious. full full of extasy [sic]

Letter from Charlotte Cushman to Emma Crow Cushman, July 27, 1860

The Emmas (Emma Crow and Emma Stebbins) were not the only women that fell for Charlotte, nor the only ones that the actress wrote love letters to. After all, “Miss Cushman possessed in a remarkable degree the power of attaching women to her” (Boston Daily Advertiser, Charlotte Cushman, Feb 19, 1876). I leave it up to you whether you want to know more about those romances and flirtations. Feel free to look through our collections, exhibits, and timelines. You might also be interested in items tagged with “same-sex attraction,” “public intimacy,” or “love.”

Obviously, your experience and interests may be very different from mine, which is why I invite you to browse the items, exhibits, timelines, and maps on your own after reading this piece. Go and find your own treasures. You can start here.

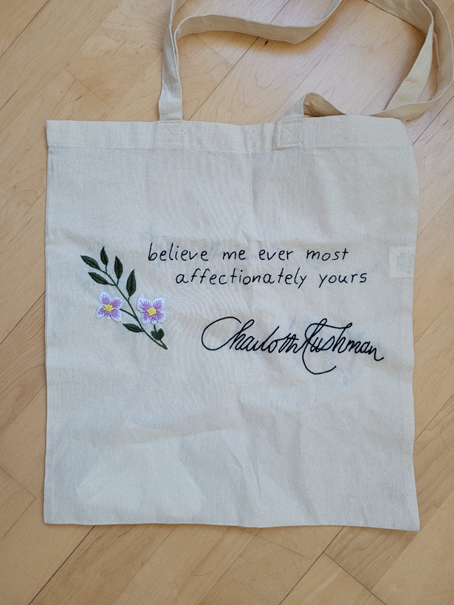

And I will end this blog post now with the only appropriate greeting after having transcribed hundreds and hundreds of Cushman letters:

Yours ever affectionately (aw, I waited so long to sign with this for one of my blog posts)

Selina

For visual input: