Concluding Remarks

The Archive as a Space that Actively Shapes Narratives

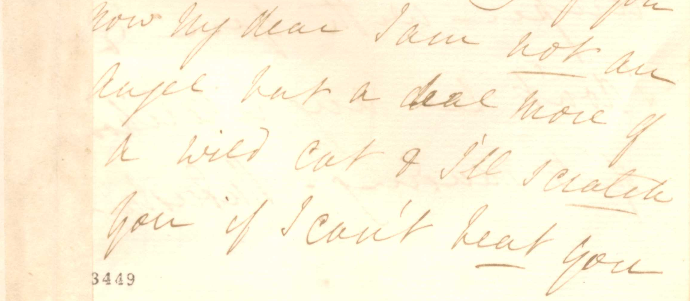

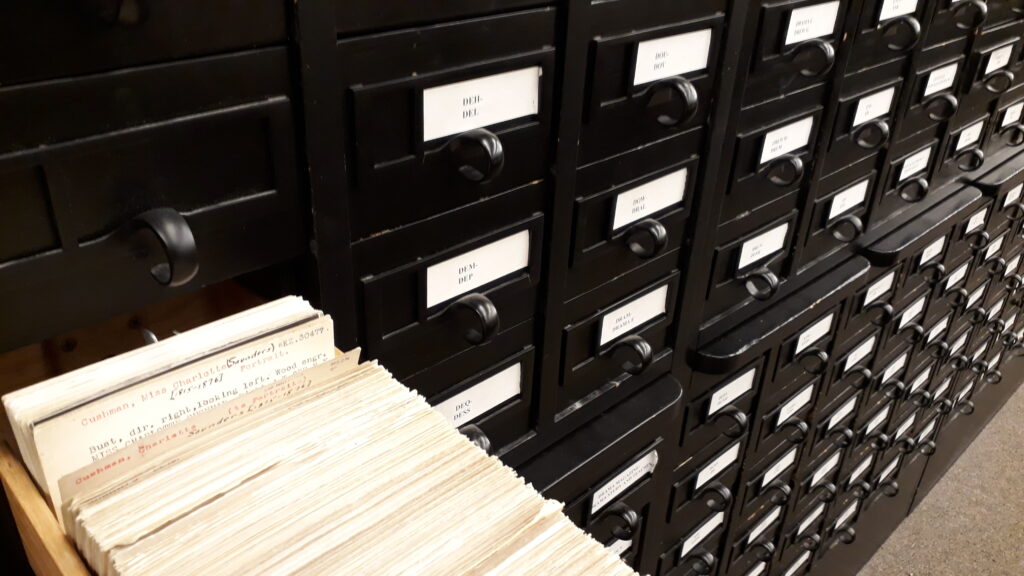

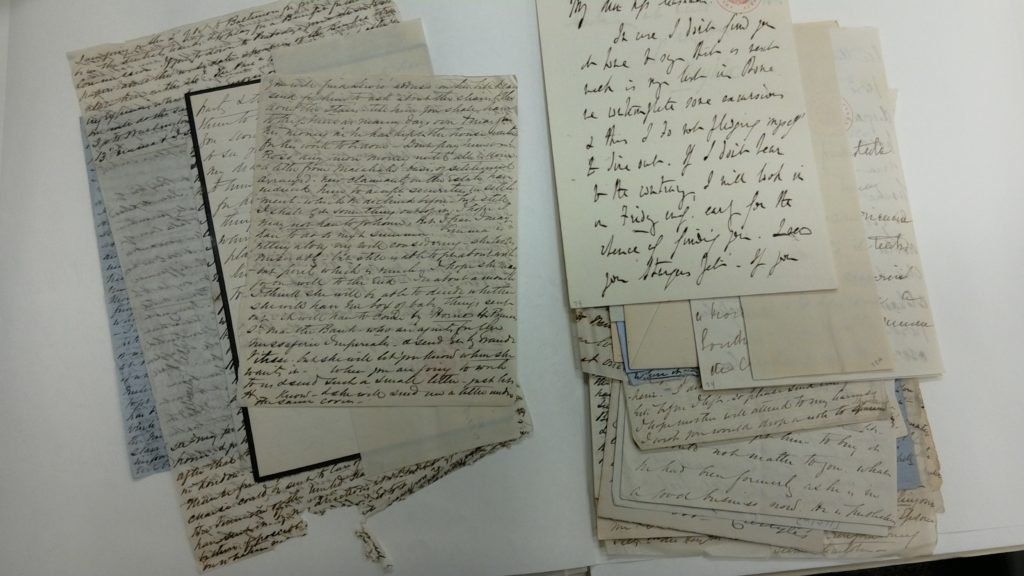

Further problems that we have encountered were that parts of letters may be missing, letter pages may be assembled in the wrong order or they were assigned to the wrong historical agent (LoC, CCP 10: 3004-3007). Transcribing the documents, we noticed from time to time that a folder contains other senders or addressees as those indicated on the compiled folders. In such cases, it is important to question the arrangement of historical documents by the archives/archivists. Dever et al. remind us that the archive is a space that constructs narratives based on the knowledge that archivists have about the collections and their comprised documents:

[A]ny contemporary discussion of archival research must begin by acknowledging the epistemological pressure placed upon the concept of ‘the archive’ in recent years. This pressure has marked a turn away from the positivist understanding of archival repositories as being mere storehouses of records, toward considering the status of the archive as a significant element in our investigations. Ann Laura Stoler characterises this shift as the ‘move from archive-as-source to archive-as-subject’. […] [Jane Taylor’s] conclusion–that the archive is ‘at once a system of objects, a system of knowledge and a system of exclusion’–points to the profoundly constructed and deeply political nature of the archive, challenging many hitherto basic assumptions about ‘archival fixity and materiality’.

(Dever et al. 105, 118-119)

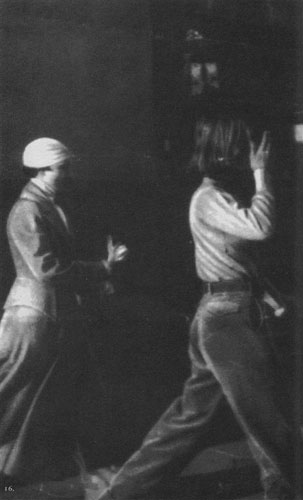

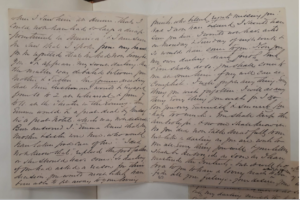

Critiquing her own use of private documents and tacit knowledge in archival documents, Sally Newman challenges her own position as a researcher to discuss her initial research focus and the assumptions with which she worked on the material at first, oscillating between nostalgia and fantasy. She researched in the Smith College archive to investigate same-sex desire:

I was drawn by their colour and materiality, even as it seemed there was something other-worldly about the splashes of brilliant blue that lit up the dour grey pages of the thick leather-bound books in which students immortalised their college experiences. This paradoxical presence/absence only heightened my desire for these objects and allowed me to indulge in the fantasy of seeing through these miniature portals into another time and place. I enjoyed the delight that was obvious on students’ faces in their playful mugging for the camera at ‘Mock Weddings’, which seemed to capture the spirit of this progressive ‘Adamless Eden’ that I was experiencing vicariously as I worked my way through the archive.

(Newman 153)

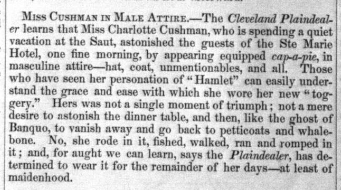

Newman concludes that her “desire (for these objects, for what they represented for my project) had prevented … [her] from seeing that these artefacts were linked by something more obvious: the desire to memorialise experiences and culture” (Newman 157). She calls for using the term ‘archive’ in the pural since what researchers make of the material they encounter is exposed to interpreting skills coming from all sorts of different angles: “There is no single archive because readers will construct their own ‘archive’ from the artefacts they choose to highlight, ignore or pass over” (Newman 155). Hence, our online archive and exhibits are a particular way of storytelling. The Omeka collection is constantly evolving in terms of size and specificity. In the DFG project, we trace gossip as a form of knowledge production and circulation in auto/biographical writing (both published and private) to investigate women’s (individual and communal, secret and shared) strategies in dealing with socio-cultural forces of financial speculation, the re-evaluation of privacy, and new forms of participation in the public sphere. For the Omeka collection, we have focused on actress Charlotte Cushman so far. The collected and digitized material is not limited to documents that explicitly mention gossip. The collection comprises

Read more