The time has come for me to say goodbye to the archive. As a student assistant, I worked on the collection over the last six months. After sifting through hundreds of items – letters, articles, diary entries, and so much more – there were many that stuck out to me for different reasons. Charlotte Cushman lived such an interesting, eventful life that it is quite hard to narrow down my favorite items, but I will attempt to do so nonetheless.

Charlotte Cushman’s Gender-Bending Performances

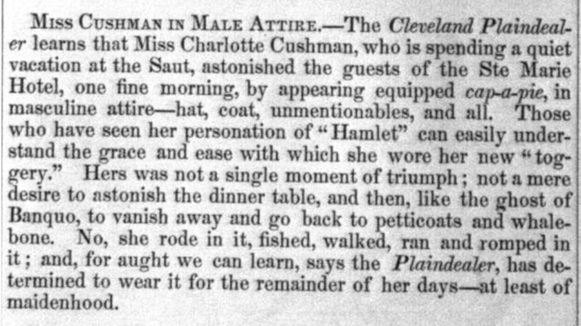

What immediately drew me to Charlotte Cushman were her famous gender-bending performances as Shakespeare’s Romeo and Hamlet. Consequently, I was thrilled to discover that even in her private life, Cushman refused to conform to the gender roles of her time, as mentioned in this article in the Illustrated American News which my fellow student assistant Arunima Kundu discusses in her blog post. In addition to her well-documented intimate relationships with women, Cushman enjoyed wearing men’s clothing while she was out and about – “hat, coat, unmentionables, and all.”

“MISS CUSHMAN IN MALE ATTIRE”, Illustrated American News, Aug 9, 1851, link.

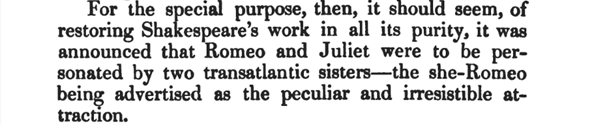

During her theatrical career, Cushman acted the Romeo to her sister’s Juliet in Shakespeare’s famous tragedy, prompting reactions from the public that were… mixed, to say the least. Let’s have a look at what some of her critics had to say:

One author states that “the Juliet of Shakespeare deserves at least a man for her lover” (380) and he „will waste no words upon demonstrating the disgustingly monstrous grossness of such a perversion“ (379), calling Cushman a „she-Romeo“ (without explicitly naming names).

The author goes on to lament that “we live in a time when there are men with so little manhood as to have almost lost all sense of the essentially different manner in which this passion, especially, manifests itself in the two sexes respectively” (380). Cushman’s Romeo really seems to have hit a nerve and I was reminded of current discourses surrounding traditional manhood – it appears as though no matter the time period, there are always voices mourning the death of ‘proper’ masculinity.

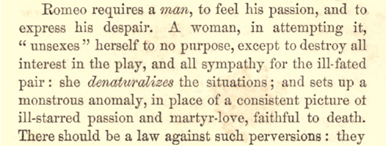

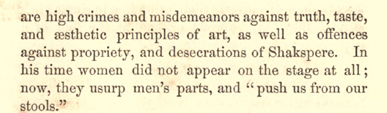

Fellow actor George Vandenhoff felt similarly about Cushman’s Romeo: In his autobiography he critiques that she “denaturalizes” (217) the situations of the play through her performance; after all, Romeo needs to be played by a man and casting him as a woman destroys “all sympathy for the ill-fated pair” (217). But even worse: He worries that male actors are losing their roles to women! Something that never would have happened in the good old Shakespearean times, when all roles were played by men.

Double standards and crises of masculinity aside, there are plenty of reactions to Cushman’s performance that brought a smile to my face – for example this review from the People’s Journal:

A dangerous young man indeed. For those curious, the French translates to “For our words are always suppressed when feeling transcends expression”. Cushman’s transcendental performance even prompted an admirer to dedicate a poem to her „personification of Romeo” that praises her beauty and presence:

I liken thy glance to the gorgeous dyes

“TO MISS CUSHMAN’S PERSONIFICATION OF ROMEO“, Liverpool Mercury, Aug 14, 1855, link.

That spread over earth’s evanishing bowers

When nature, resplendent in loveliness, sighs

Her impassioned adieu to the beautiful flowers.

Thy lip I will paint as the bright coral thorn,

That yields to the voyager its delicate bloom;

And thy smiles, as the kisses that glitter at morn,

And bathe the young roses in Eden’s perfume.

Thy voice! ‘Tis the cadence, the silvery play,

That murmurs response to the mariner’s song,

When his oars part the tresses of beauty that stray

O’er the zone of the waters the moonbeams smile on.

Brightest and dearest, thy coming resembles

The sound of a lute when it floats on the wind;

For where thou hast trodden an echo yet trembles,

Like the spirit of beauty thy presence defined.

Mansfield House.

And this is far from the only poem written about Charlotte Cushman! In this poem, for example, Eliza Cook claims that her “brain never had become such slave / To Fiction, as it did beneath [Cushman’s] power”.

I think the effect of Cushman’s Romeo on her admirers can be best described using this excerpt from Harriet Prescott Spofford’s article in which she celebrates „The New England Girl“.

„I see Charlotte Cushman, who in Romeo taught men how a woman wishes to have love made to her, in her youth with men at her feet, in her later life with all women there.”

“The New England Girl,” The Woman’s Voice, Jan 17, 1895, link.

It seems that despite all the criticism she received, Cushman’s gender-bending performances spoke to women and men alike and what prompted scorn from her critics – her voice, her features, her clothing – were the attributes that others admired. Charlotte Cushman appeared in gender-non-conforming dress both on stage and in her private life, showing that even in the 19th century, she made room for her own queer gender expression.

I am glad to have had the opportunity to work on the collection, especially because of the fascinating window it offers into queer history. Of course, this post only shows you a small selection of items and I encourage visitors to go digging through the archive themselves – you never know what gems you might stumble upon! And fun fact, if you are interested in gender norms and those who break them, there are currently about 200 items in the collection with the subject heading “gender norms” that might interest you.