On the Provenance of the Charlotte Cushman Papers at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

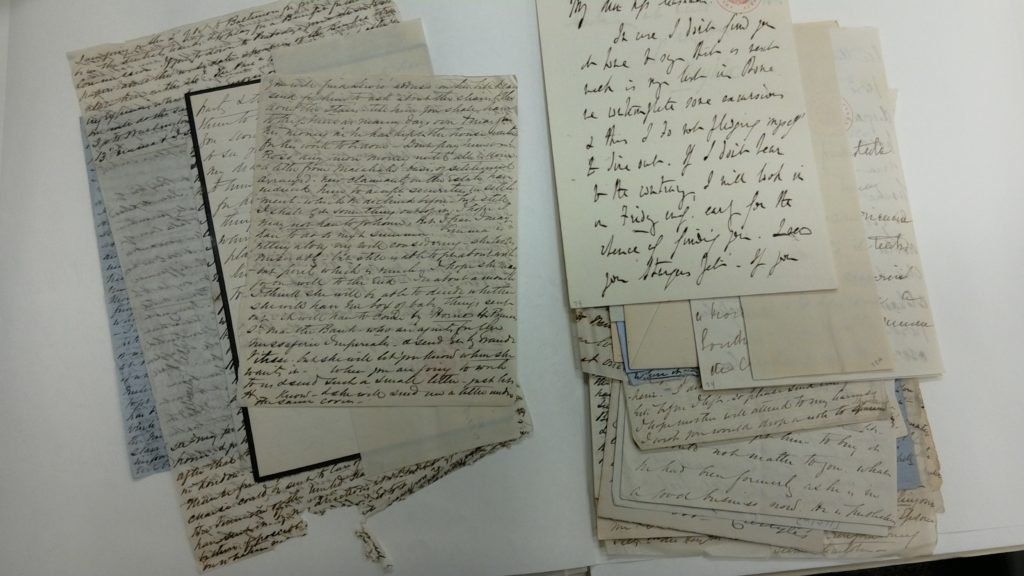

Much of the material I read for our research project (letters, diary entries) is of a very private nature. This raises ethical concerns as well as methodological issues:

But what does it mean to begin to sift the available traces of someone’s life? Where do the boundaries lie between private lives and public scrutiny? […] How do we make sense of surviving traces of their private lives that have found their way into public archives? What protocols govern scholarly attention to these particular aspects of the archival record?

Dever, Maryanne, et al. “The Intimate Archive.” Archives and Manuscripts, vol. 38, no. 1, May 2010, pp. 94–137.

It also raises very practical questions – some of which struck me immediately upon sitting down in front of one bound book of Charlotte Cushman’s personal correspondence (decyphering the handwriting, storage of data), some of which took a while to dawn on me. Most importantly:

How did these letters get here???

The finding aid gives the following (sparse) information on the provenance of the Charlotte Cushman Papers at the Library of Congress:

The papers of Charlotte Cushman, actress, were given to the Library of Congress by Victor N. and Louise Cushman in 1925 and 1927. Additional material was given by Charles V. B. Cushman and others via Lyman Beecher Stowe from 1949 to 1955 and by Ethel B. Clark in 1947. Other items were purchased by the Library from 1957 to 1990.

Charlotte Cushman died in 1876, which leaves a 50 year gap between her death and the appearance of the letters in the Library of Congress.

From the letters between Cushman’s partner and biographer, Emma Stebbins, to Sidney Lanier, one learns that Stebbins started to collect correspondence in 1876 in preparation for Charlotte Cushman: Her Letters and Memories of her Life. So far, however, I have found nothing in these letters between Stebbins and Lanier about whether Stebbins returned or kept the material requested from family and friends.

In 1941, another biographer, Lyman Beecher Stowe, left a much clearer record of his attempts to collect sources for his planned biography of Charlotte Cushman. He also noted down his plans to donate (jackpot!) his collection to the Library of Congress. His correspondence with descendents of Cushman and others who had responded to his request in several magazines to send him relevant material, is part of the Beecher-Stowe Family Digital Collection at Schlesinger Library.

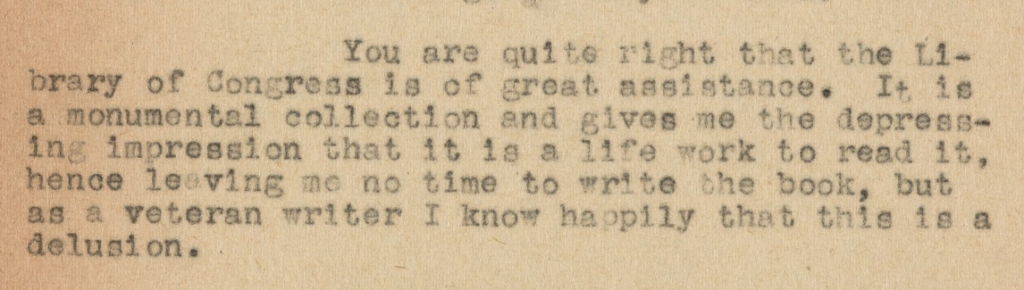

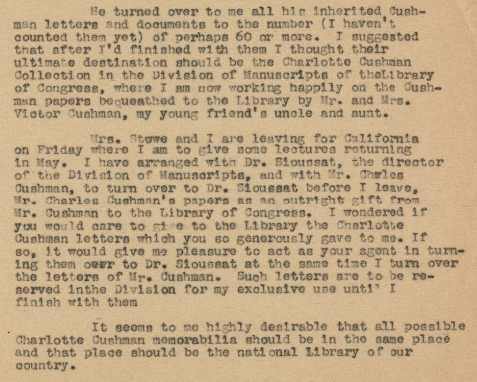

Stowe himself donated his collected material to the Library of Congress between 1949 and 1955. This decision was obviously prompted by the seemingly already sizable collection of Cushman-related material held in the Manuscript division on which he based his initial research (Stowe also mentions the Fields Collection at Huntington, see their finding aid for more details) :

Central to Stowe’s endeavour to add to this publically available collection were private letters which several family members of Cushman offered to send to him. (Before you get your hopes up about a brilliant, but forgotten Cushman biography: Stowe took a break from working on the biography to support the war effort and then got discouraged because work continued “at a snail’s pace.” Which: #HardAgree). Charles Cushman, for example, writes to Lymann Beecher Stowe on Feb 12, 1941:

I have several portraits, also a number of autographs, letters from Browning, […] Whittier etc [inserted] to Charlotte Cushman. I should be very glad to have you examine everything that I have that concerns C.C. […] My aunt Mrs Victor Cushman, and my Uncle Col. Jay [?] Cushman are the last of the older generation, who have connections and memories of the days when Charlotte Cushman was a world famous person. I have always revered her memory, and I am glad to have inherited some of her portraits and letters. A few years ago there were still many people alive who were steaped in memories of her, and I believe both my uncle and aunt can help you.

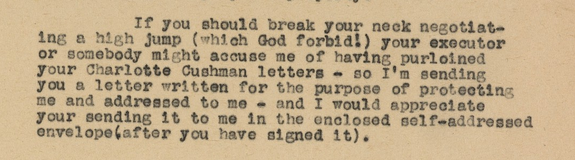

On March 12, 1941, Lyman Beecher Stowe responds to Charles Cushman apologetically that “I know you hate to write […] However […] I like a letter when I have in my custody other people’s property.” And so he ask Charles to sign a form to make the transfer of letters official:

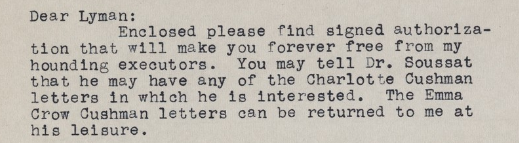

In an overlapping letter from March 13, Charles Cushman reacts to Lyman Beecher Stowe’s oral suggestion to turn over all letters to him and to later donate the material to the LoC. In his reply to Beecher Stowe’s written request, Cushman excludes the letters by Emma Crow Cushman, stating that they can should be returned to him:

On March 10, 1941, Stowe corresponds with Miss Laura Wheeler to suggest he turns her Cushman-related material over to the Library of Conress at the same time as he delivers the letters provided my Charles Cushman (follow-up from Sep 25, 1941):

On December 8, 1941, a descendent of Longfellow, Harry Dana, offers Stowe access to Charlotte Cushman’s letters to her grandfather. Stowe promises to visit. In 1942, Stowe informs Charles Cushman that he has given up on his plans to write the memoir. He asks for permission to hand over his aunt’s material together with Charles’ to the Manuscript Division.

After this, the Beecher-Stowe Family Papers offers no further insight on what happened to the material collected by or offered to Stowe. I am, hence, left with A LOT of questions, for example:

- what became of this source suggested to Stowe about a supposed Cushman love affair?

- What became of the Emma Crow-letters that Charles Cushman seemingly wanted back?

- Where are the letters from Emma Crow to Charlotte Cushman?

- Why does this random stranger (Geo.R. Spalding?!) have letters from Cushman to her mother?

So … after digging through Stowe’s notes for two days, I have more questions, than answers (or actually: a have still more questions). But at least, they are a bit more specific?

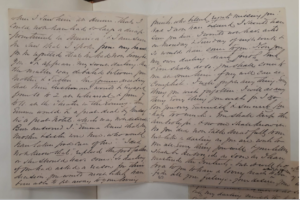

When dealing with collections of letters, we are inevitably confronted by what we might call the ‘fissured archive’. What survives of anyone’s letters will be but a fraction of the total, and their survival will be dependent, more often than not, on accident rather than design. […] we are left all too often with an archive that resembles a fishing net: the few threads (and an occasional judicious mending) held taut over pockets of nothingness.

Dever, Maryanne. “Reading Other People’s Mail.” Archives and Manuscripts, vol. 24, no. 1, 1996, pp. 116–29.

ps.: if you know the answers, talk to me!

(author: Katrin Horn)

One thought on “Attic to Archive”