incl. my Paper on:

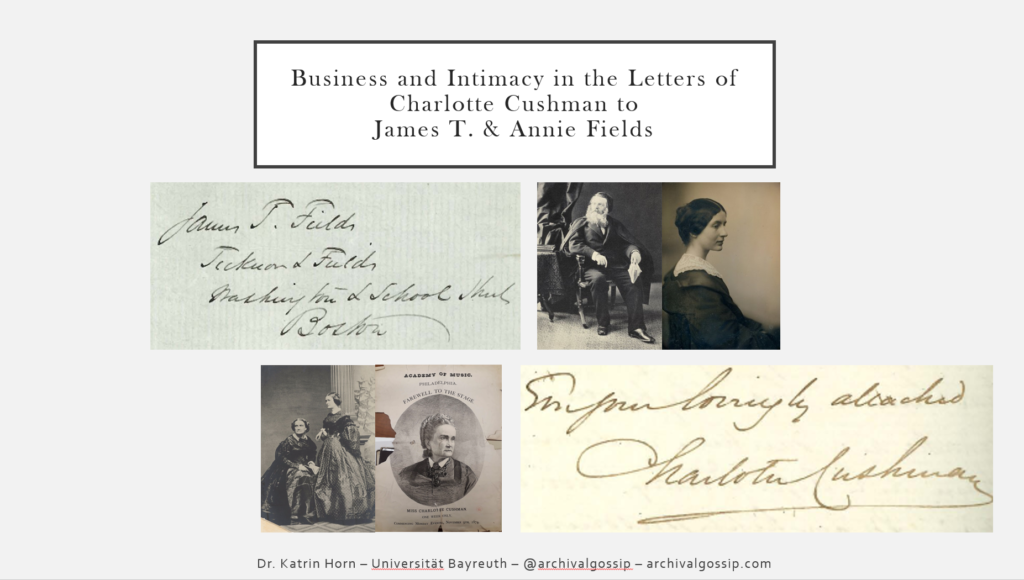

Business and Intimacy in the Correspondence of Charlotte Cushman and James T. & Annie Fields

Yesterday, I had the great pleasure to chair a panel together with the incomparable Dr. Laura Rattray at this year’s digital conference of the British Association for American Studies. And what can I say, I had an absolute blast!

Here’s a rundown of our panel on Transatlantic Women’s Letter Writing of the 19th and early 20th Century, and below that my paper in full.

The roundtable session brought together an international group of academics and archivists to reconsider transatlantic networks of correspondence specifically via women’s letter writing. The timeframe, the nineteenth and early twentieth century, seemed particularly pertinent to us, as the nineteenth century witnessed a growing public presence of women and increased (transatlantic) mobility and thus more and more transatlantic relations and communications. At the same time, the letter lost its “public nature and function,” as Maryanne Dever puts it (117). By the twentieth century, letters were no longer expected to be read to and circulated among friends and families. Instead, “a sense of assumed intimacy breathes from every line” (Spacks 70–71). Between these two extremes, letters could take on many forms, often containing parcels and books, selective passages that were meant to be read allowed or copied to additional recipients, some marked as “to be burned” after reading, with others intended to be published in print.

When Laura and I conceived of this roundtable, we were especially interested in the letters of women with public careers. For middle and upper class women in general, letter-exchange was both a daily practice and thus an everyday occurrence, as it was “an inadvertent powerful practice [that] can be read as a form of exercising female agency” (Simon-Martin 10–12) – or as Maria Tomboukou puts it, letters are “ a discursive technique of safeguarding solitude while sustaining communication, a paradox of the social self” (1).

With our focus on professional women (artist, authors, activists), we wanted to additionally explore how “private” letters contradict or complement these women’s public perception, how correspondence might have been used to support their careers and activism, and how letters might even complicate the common distinction between public and private to begin with.

Correspondences are therefore a highly insightful and fascinating object of study—but also a challenging one. Particularly those of us trained in literary studies, for example, might need to ‘un-train’ some of our methods. As Daniel Karlin, editor of the letters between Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett warns: ‘the correspondence has a plot of which the letters themselves could not be aware” (xii). While we read these letters as a continuous story, there were written and received often with long gaps of time in between, especially as they crossed the Atlantic. Additionally, different parts of letters could take on different meanings: Stationary could tell their own story, as could handwriting or modes of address – especially in correspondence among people of different status and unequal power relations.

Beside these historical and theoretical concerns, we also designed the panel to address the practical concern of working with letters, many of which only available in archives. Our participants therefore considered issues of access and digitization, transcription and preservation that illustrate the status of life writing in scholarship and the different modes of telling transatlantic stories that would otherwise be inaccessible.

Our panelists:

Etta Madden (Missouri State University) illuminated the emotional gaps between the “Letters from Rome” Anne Hampton Brewster (1819-1892) wrote for the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin and the Boston Daily Advertiser and private letters she received, which prompted outpourings in her diaries. For more than twenty years Brewster’s bolstered the professional profiles of artists such as Harriet Hosmer but also inflamed jealousy among writers such Anna Edwards, who sought her support. (Twitter, Blog)

Considering the implications of letters that Frederick Douglass sent from the U. S. to Britain, during the Civil War, Sarah Meer (University of Cambridge) argued that it was Julia Griffiths who passed these to a British newspaper, and that their printing drew, paradoxically, on the authenticating prestige bestowed by the sense that they were private testimony.

Elizabeth A. Novara (Library of Congress) reflected on the use of women’s letters in public engagement and outreach efforts, including a gallery exhibition and online crowdsourced transcription campaigns, during the United States women’s suffrage centennial. Letters discussed will document the importance of personal relationships, transatlantic connections, and political ambitions of correspondents such as Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Blackwell, Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Chapman Catt, and Nellie Quander. (If you haven’t done so yet, you should all explore the Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote online exhibit which Liz co-curated.)

Julie Olin-Ammentorp (Le Moyne College) discussed the letters of Willa Cather (1873-1947) from France, focusing on Cather’s first trip in 1902, at age twenty-eight. The lifelong Francophile wrote both public letters documenting her trip and personal letters to friends and family members. Paradoxically, while the personal letters reveal her deepening admiration for French culture, it is in the public letters that she reveals her growing ambitions as a writer.

Laura Rattray (University of Glasgow) discussed the unpublished correspondence between Edith Wharton (1862-1937) and art historian Mary Berenson (1864-1945). While Wharton’s friendship with Mary’s (in)famous husband, Bernard Berenson, has long taken centre stage, this short talk considers the writer’s complex negotiation of public gossip and private revelations, with a rare intimacy and vulnerability revealed through correspondence with her female friend.

Works Cited

Dever, Maryanne. “Reading Other People’s Mail.” Archives and Manuscripts 24.1 (1996): 116–129.

Karlin, Daniel. Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett: The Courtship Correspondence 1845-1846. Clarendon Press, 1989.

Spacks, Patricia Meyer. Gossip: A Celebration and Defences of the Art of ‘Idle Talk. Alfred A. Knopf, 1985.

Barton, David, and Nigel Hall. “Introduction.” Letter Writing as a Social Practice, edited by David Barton and Nigel Hall, John Benjamins, 2000, pp. 1–14.

Simon-Martin, Meritxell. Barbara Bodichon’s Epistolary Education: Unfolding Feminism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

Tamboukou, Maria. “Visual Silences, Nomadic Narratives.” Auto/Biography Yearbook Vol. 2. Russels Press, 2008: 1-20

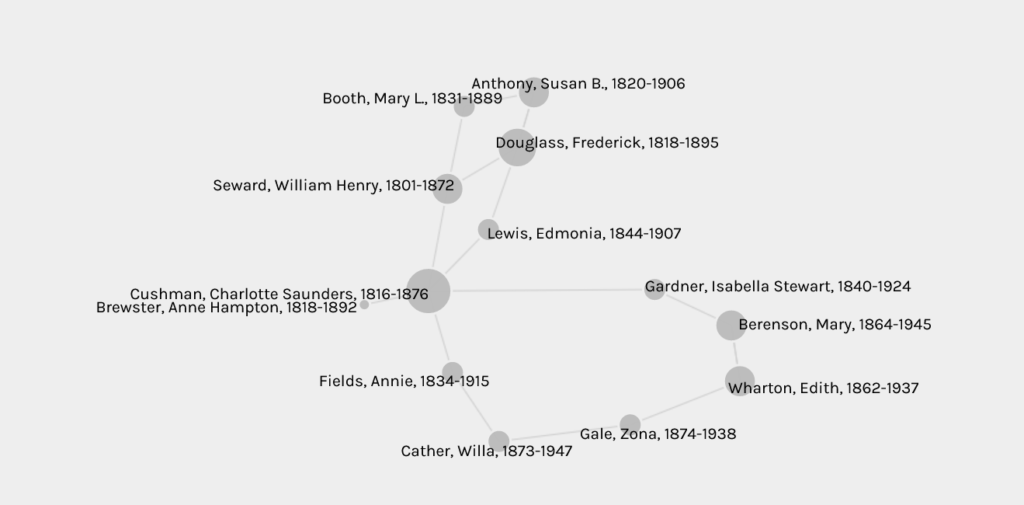

Correspondence between Charlotte Cushman and James T. / Annie Fields

My original idea for this panel was a kind of “six degress of separation”-thing where the talks are accompanied by a interactive network graph. Even as our plan for the panel developed into another direction, I couldn’t quite let of this idea. And so I (with the help of Selina, as usual) wanted to check my hypothesis of the “six degrees of separation” of basically all anglophone women in the nineteenth century.

And, lo and behold: Cushman can be connected with the central figures of the other five talks in our panel with no more than three letters!

But now for the actual talk:

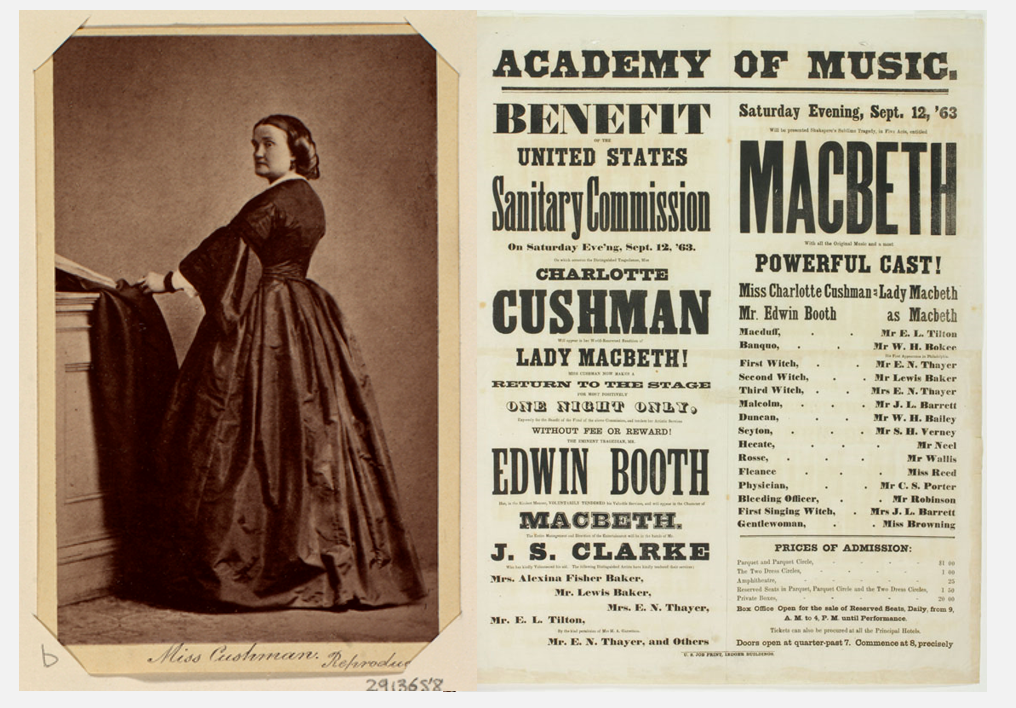

In 1863, Charlotte Cushman – the first US American actress of international renown – returns to the US to tour in support of the Sanitary Commission. Cushman had left for England in 1844, and – after a brief stay in the US – had settled (‘retired’) in 1852 in Rome.

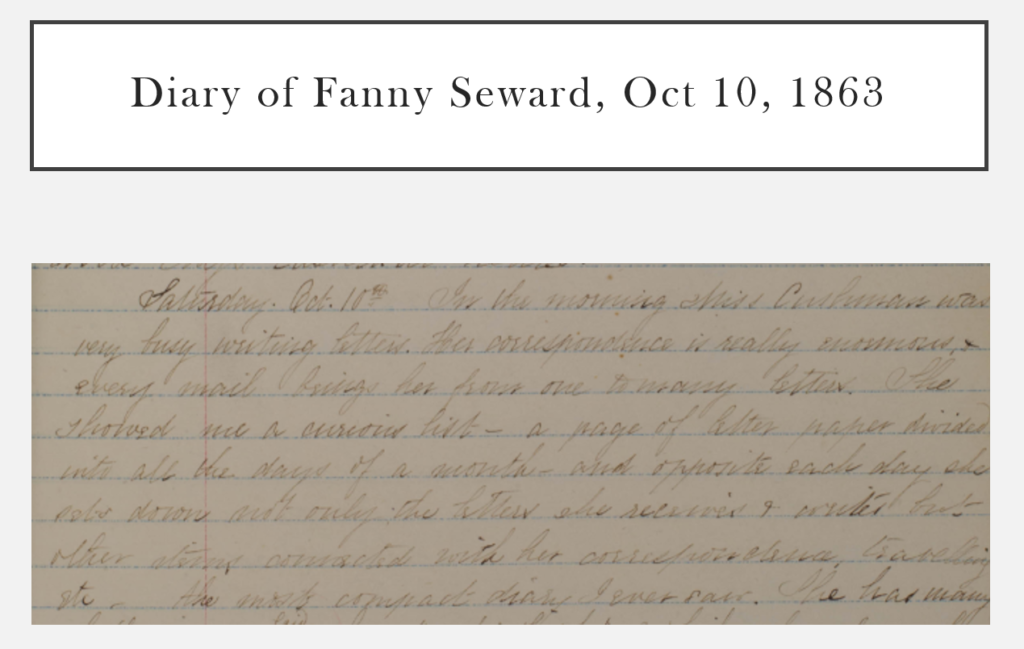

As a staunch patriot and supporter of the Union cause, Cushman decided to return to the stage once more. Well connected as she was among the cultural and political elite, she stays at the home of US Secretary of State William Henry Seward. His daughter Fanny, smitten with Cushman from day one, notes in her diary on October 10, 1863:

In the morning Miss Cushman was very busy writing letters. Her correspondence is really enormous, & every mail brings her from one to many letters. She showed me a curious list – a page of letter paper divided into all the days of a month – and opposite each day she sets down not only the letters she receives & writes but other items connected with her correspondence, travelling, etc. The most compact diary I ever saw.

I’d give a lot for that diary!

Thankfully, much of Cushman’s voluminous transatlantic correspondence is still preserved. Most of her written legacy is held at the Library of Congress, whose “Charlotte Cushman Papers” boasts 10,000 items. Today, however, I want to focus on a large collections of her letters held at Huntington rather than the Library of Congress, namely her letters from Italy, England, and the US to publisher power-couple James Thomas and Annie Fields. These contain some of the most overt interweaving of business concerns and interference with public perception on the one hand, and exchange of quotidian and intimate information on the other.

(All letters quoted below – and lots of others! – can be found in our exhibit “The Fields and Cushman”)

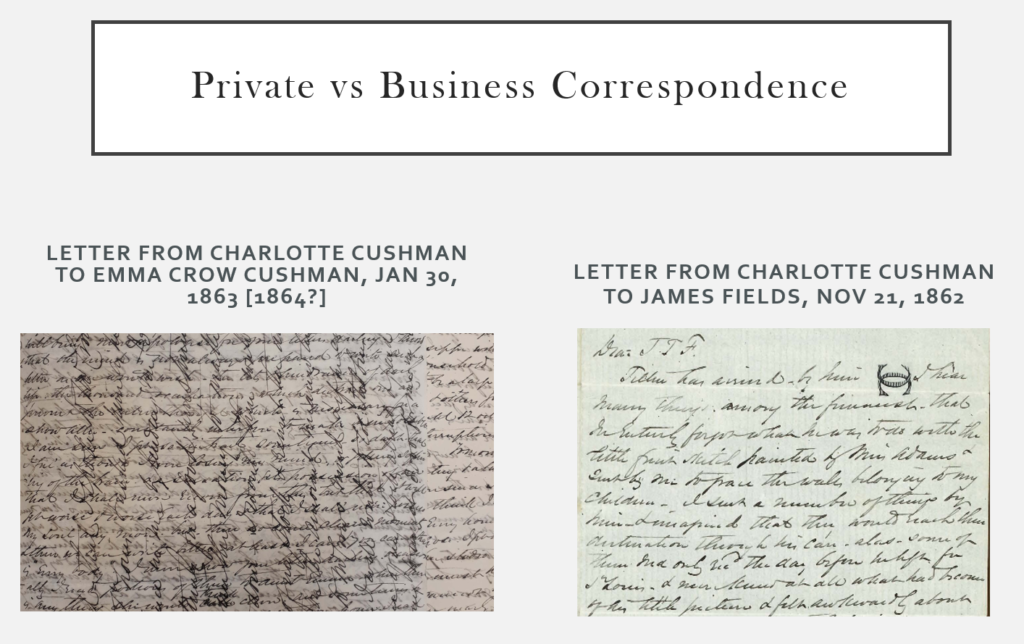

There’s quite a few things we can tell just by looking at (rather than reading) leeters.

-

- Visual contrast between letters addressed to “intimate friends” (such as ECC / maybe the earlier to Greenwood, too?) and the more “formal letters” to the Fields

- impression of her mobility as addresses and letter heads constantly change; letters are, after all, the “genre par excellence of mobility” (Sarah Pearson)

My main interest in Charlotte Cushman as an object of study is her approach to managing her public reputation. She was the US most celebrated actress – yet she defied nineteenth century gender norms, and remained unmarried her entire life. That is: she was never legally married. Her diary and her letters confirm that she considered herself married at least twice in her life, both times to women: to painter Rosalie Sully before her breakthrough in the 1840s, and then to sculptor Emma Stebbins for the last decades of her life. As such, Cushman was – to borrow from historian Victoria Harris – “marginally normal,” that is: if we look to history, especially the history of sexuality, we can’t only focus on the deviant, those clearly outside the margins of what was considered acceptable. Instead, “the margins …. must also be understood as the space just on the ‘good’ side as well” (1099). And that’s where we would find these respectable, white, middle-class women with unusual professions and have same-sex relationships. That fine line between normal (even idealized) and deviant is also found in their correspondence with the Fields.

Emma Stebbins would later also publish Cushman’s biography (fittingly called: Her Letters and Memories of her Life), in which she – characteristically for the genre – and only acknowledged that “it was in the winter of 1856-57 that the compiler of these memoirs first made Miss Cushman’s acquaintance, and from that time the current of their two lives ran, with rare exceptions, side by side” (Stebbins 100). Their lives thus also ran “side by side” during the time that Cushman cultivated her friendship with the Fields, beginning in 1860. Thanks to James’ position as the publisher of the Atlantic Monthly and Annie’s own writing and networking, the couple were clearly valuable friends for someone depended for their success on public opinion. Cushman was, to cite Stebbins once more, “as all the world knows, a clever woman of business” (98). As such, much of the transatlantic correspondence with the Fields is dedicated to business matters, in which she tries to influence events in the US from abroad by proxy. In her biography of James, Annie Fields writes: “It is amusing to see how full [Cushman’s] letters are of suggestions for forwarding her own plans or those of others in whom she was interested” (74).

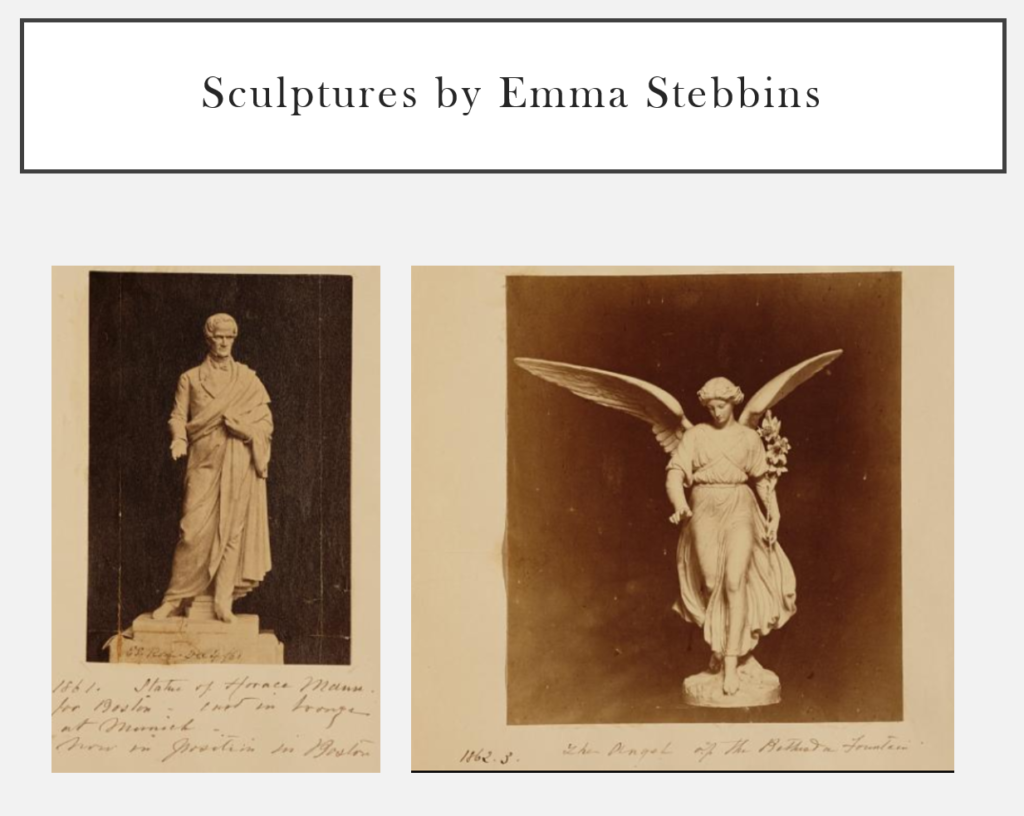

Key among those others “in whom she was interested” was Emma Stebbins. Her support for Emma Stebbins’s career is among her most sustained efforts in the letters still available to us – which is in and of itself telling. Her first project: ensure payment for Stebbins’ sculpture of Horace Mann. Her second: the commission of what is now known as Bethesda Fountain in Central Park, and afterwards: good press for the sculpture (rumored to be modelled after Cushman herself).

Given this “business interest,” the correspondence oscillates between and often combines Cushman’s blunt management of her and Stebbins’ public perception and intimate communication of the relationship with Stebbins, whose exact nature seemingly remains an open secret.

Some letters, for example, imply Cushman’s and Stebbins’ status as a couple (even a married couple) equally in how the Fields write to them and interact with them, and in how Cushman mentions Stebbins and their shared life in her letters. Some stress this in how they are signed, such as

-

- “Charlotte & Emma” – in the letter in which CC asks James to intervene on Stebbins behalf and get Howe to pay for the Horace Mann statue (which is waiting to be cast in Munich) (Dec 31, 1864)

- “with love from Emma” (1860)

- “with kindest love from the Duo” (Sep 5, 1868)

Others acknowledge that they both received shared book packages (July 25, 1869) or discuss shared vacation plans and invitations to join them (Aug 25, 1860) / (July 30, 1868).

Some letters are even relatively explicit in “naming” the relationship between Stebbins und Cushman, such as the one from Christmas, 1860, in which Cushman laments “I feel so lonely without my other, & much very better half” (Dec 25, 1860).

Such terms of endearment make way for more neutral expressions, when Stebbins’ sculptures are discussed. In 1868, Cushman writes to Annie Fields: “& when [Emma Stebbins’ angel) is set up in New York. it will be without exception the most magnificent Thing in our country & you & I will then be proud of our friend” (Feb 26, 1868). “Our friend” might seem to us like a step back from “much better half,” but strategically it makes sense at this point to stress Stebbins’ relation to all of them, and thus pave the way for The Atlantic to do its part in influencing “the obedient sheep”, as Annie Fields calls the US American Public in another letter to Cushman (AF to CC Feb 5, 1868).

Lisa Merrill, in her superb study When Romeo was a Woman, argues that “with Emma Stebbins, Charlotte enacted an ‘idealized view’ of women’s loving relationships, which, paradoxically, appeared to many people to exemplify conventional societal values rather than challenge them” (196). For the most part, I would agree with this assessment. Yet, given the ideal of passionlessness for women in general, for “intimate friendships” in particular, and for Cushman herself especially, the occasions when Cushman deviates from this ideal are all the more noteworthy. One striking example occurs, when Cushman steps in to defend Stebbins and her work.

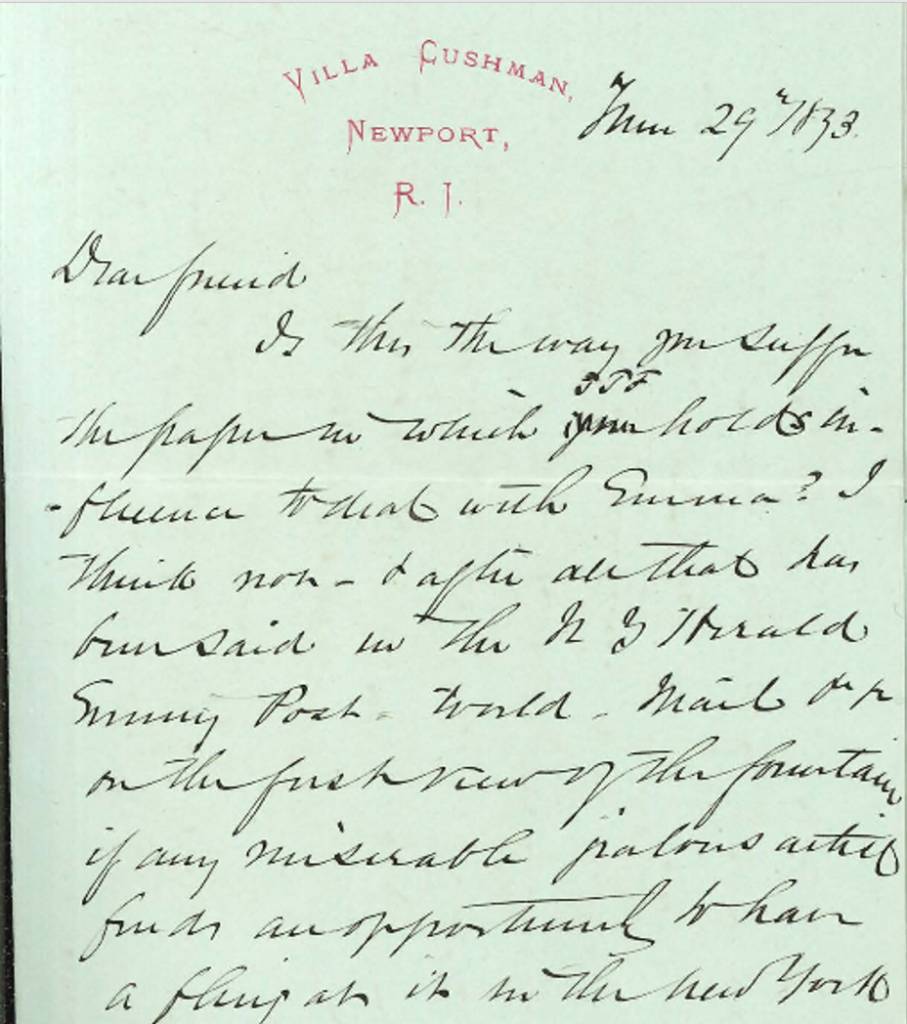

This letter addressed to Annie Fields, on June 29, 1873, I can’t help but adore its righteous indignation and rage:

Is this the way you suffer the paper in which you JTF [inserted] holds influence to deal with Emma? I think not — …. it ill becomes a Boston paper which once had a reputation for decency & honesty to print such a libellous thing as this which I enclose. I wish you would have some thing said in The Transcript which shall stultify the effect of the enclosed vileness — which +++ has a personal sting

It is one of the rare occasions, in which Cushman starts without the usual pleasantries, and in which she speaks simply of “Emma” (not Emma Stebbins, Emma S., or “our Emma”) – repeatedly, in fact, as her protectiveness is stressed later in the letter again, when she states that “I would not have Emma see this for the world.”

In distingiushing among forms of life writing, Patricia Mayer Spacks argues that “Letters differ from autobiographies partly in exerting less continuous control over the construction of a life-myth” (69). This letter would certainly be such a loss of control over Cushman’s life-myth of portraying herself as passionless. And as such, it becomes – as does much of the correspondence – despite its business-focus, intimate in its own way.

Works Cited:

Harris, Victoria. “Sex on the Margins: New Directions in the Historiography of Sexuality and Gender.” The Historical Journal 53.4 (2010): 1085–1104.

Fields, Annie. James T. Fields. Biographical Notes and Personal Sketches, with Unpublished Fragments and Tributes from Men and Women of Letters. 1882.

Merrill, Lisa. When Romeo Was a Woman: Charlotte Cushman and Her Circle of Female Spectators. University of Michigan Press, 2000.

Pearsall, Sarah M. S. “Letters and Letter Writing.” Oxford Bibliographies Online Datasets, 1 Jan. 2012 Atlantic History.

Spacks, Patricia Meyer. Gossip: A Celebration and Defences of the Art of ‘Idle Talk’; a Brilliant Exploration of Its Role in Literature (Novels, Memoirs, Letters, Journals) as Well as in Life. Alfred A. Knopf, 1985.

Stebbins, Emma. Charlotte Cushman: Her Letters and Memories of Her Life. 1878.