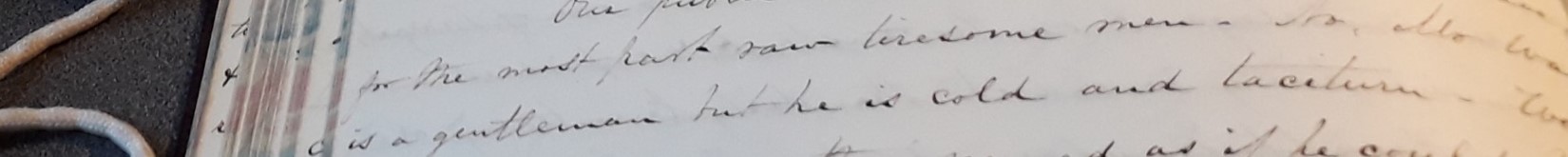

Athenaeum, Cushman Mentions, Jan-June 1845 (Vol. 1)

Dublin Core

Title

Athenaeum, Cushman Mentions, Jan-June 1845 (Vol. 1)

Subject

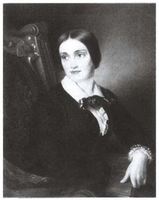

Cushman, Charlotte Saunders, 1816-1876

Forrest, Edwin, 1806-1872

Actors and Actresses

Actors and Actresses--US American

Actors and Actresses--English

Athenaeum

Fame

Praise

Gender Norms

England--London

Description

Excerpts from the Athenaeum issues from the first half of 1845, which mention Charlotte Cushman;

The passage praise Cushman as a versatile genius on stage despite at times gender-bending practices. The first volume of 1845 shows how the British press is growing increasingly attached to Cushman as an actress performing on the English stage.

The passage praise Cushman as a versatile genius on stage despite at times gender-bending practices. The first volume of 1845 shows how the British press is growing increasingly attached to Cushman as an actress performing on the English stage.

Credit

Source

Athenaeum

Date

1845-02-15

Type

Reference

Article Item Type Metadata

Text

Feb 15, 1845:

The Americans seem to be paying off, by some what liberal instalments, the dramatic debt which they have incurred to England, for the visits of her actors to the cities of the Union. Last week, we spoke of the appearance of Mr. Hackett at Covent Garden;–on Thursday in this week, Miss Cushman, an actress of Transatlantic celebrity, new to the English boards, made her début at the Princess's Theatre;—and Mr. Forrest, an old acquaintance, will renew his intercourse with the English public on the same boards, in the course of next week. The character which introduced Miss Cushman was Bianca, in Milman's poetical tragedy of 'Fazio.'

The Americans seem to be paying off, by some what liberal instalments, the dramatic debt which they have incurred to England, for the visits of her actors to the cities of the Union. Last week, we spoke of the appearance of Mr. Hackett at Covent Garden;–on Thursday in this week, Miss Cushman, an actress of Transatlantic celebrity, new to the English boards, made her début at the Princess's Theatre;—and Mr. Forrest, an old acquaintance, will renew his intercourse with the English public on the same boards, in the course of next week. The character which introduced Miss Cushman was Bianca, in Milman's poetical tragedy of 'Fazio.'

March 1, 1845:

PRINCESS'S THEATRE.—Among the desiderata of the modern stage, the most urgent has long been a great actress—one capable of sustaining the gorgeous majesty of the tragic muse. Coarseness or feebleness of execution has marred the efforts, with one or two exceptions, of the best candidates for the vacant throne; and even if they be admitted as proficients in the last graces of histrionic art, the increasing number of theatres, and the consequent distribution of talent, demands additional competitors. It was, therefore, with much gratification that we heard that Mr. Macready had discovered, in America, a lady qualified for occupying the high places of the drama. Miss Cushman's appearance in the character of Bianca, we have already announced. We have now to do with her performance of Lady Macbeth. Here the powers of the actress are tested, as already those of the poet had been, to the utmost. A heroine so sublime and terrible, that the highest intellect and quickest imagination are blended in her character—a character simply but graphically suggested by Holin shed's Chronicle—a woman "very ambitious, burning in unquenchable desire to bear the name of queen;"— but elevated, by poetic genius, into a grandeur not to be excelled. Shakspeare [sic] starts in his tragedy from a high point—all is mountain land from the beginning. The regal ambition, the unquenchable desire, is a "foregone conclusion." Long before the action of the play, the lady had proposed to her husband that "suggestion whose horrid image" should afterwards "unfix his hair, and make his seated heart knock at his ribs against the use of nature;" the "thought, whose murder yet was but fantastical," was familiar to them both, long ere the Weird Sisters had hailed the successful warrior as "king hereafter;" else would it not have so readily occurred to his mind as the only means by which the crown was to be obtained; else upon the receipt of his letter had his "dearest partner of greatness" not at once conceived the design and plan of assassination. From the moment that Miss Cushman entered, we were convinced that she had grasped this leading idea: her reading of the letter was the finest thing we have lately seen upon the stage. No living actress has approached it. The scene with the attendant and her husband, together with the intervening soliloquies, were sustained with equal power: the lines—

Her interview with the king was managed with dignity; nor did her temptation of her husband lack proper emphasis. The greatness of these scenes makes it difficult to rise above them. Shakspeare however, has piled alps on alps, and in the mountainous region which he travels, every step we take is an ascending one. 'Tis weary climbing, but the mighty business of the time compels the labour. Miss Cushman sustained it vigorously: she is greater after the murder than before; every word breathed with a separate life; every sentence glowed with accumulated expression; every gesture added to the signification of the text; not only her hand and fingers pointed, but her entire arms were instinct with the meaning of every pas sage. Perhaps in all this there was an exuberance of power, a plenitude of New-World energy, much of which must be subdued—some of it utterly de stroyed—before the actress is consummated. All this is true. Taste may have much to object—may ultimately rescind and repeal much of this abundant action. Let it be so: let all such abatements be made, let all excesses be corrected—what then remains? Power, both mental and physical; that without which there is no art, nor possibility of any; power to conceive and to embody conception; the matériel which must precede cultivation, and alone gives it value. From not sufficiently considering this, critics fall into many errors. Mr. Edwin Forrest's acting is consequently liable to much misappreciation. We remember well when this gentleman first appeared, a distinguished actor expressed high expectations from what he had previously witnessed of Mr. Forrest in the United States: "He has," said he, "all the materials of a great actor about him." This was the generous tribute of praise bestowed by a rival artist. What, however, was the decision of the public arbiters of taste? They convicted the new actor of possessing "physical power:" they took him "in the manner." Undoubtedly, Mr. Forrest has great physical power; but does it therefore follow that he has not also mental power & At first, or at last, in all great sensible operations, physical force is needful; without it, execution must fall short of desire—with it, may exceed. Nothing less than the last exponent of mental power: it may, sometimes, appear more like a principal than an agent; but even then, it is a gift which makes him who possesses it a giant among men. We confess that we can admire an exhibition of physical force even for its own sake; but we are not prepared to assert that, in the instance of the actor before us, such force is not an exponent of mental power. The attempt to prove any such negative were simply ridiculous. Many of the objections we might take to Mr. Forrest's assumption of the character of Macbeth prove, indeed, the contrary. The business, for example, is in great part different from that usually adopted on the English stage; but always has an obvious reason, even when, from its novelty or other cause, it may awhile offend a taste which has been otherwise instructed. Much of the charge has, however, now fallen to the ground; for the actor's former manner has received considerable modification, and become mellowed with experience. He has learned that repose is the final grace of art, and has subdued all natural tendencies to violence, repressing his voice and action, except in the startling crises of the play, where both, without effort, spring forth with crushing effect; not because he is an actor who chooses thus to manifest strength, but because he is a strong man, and has simply liberated his energies. All this is merely a natural advantage—but it is an advantage, and must be reckoned among the natural qualifications of an actor, unless we hold that he is best fitted for the stage for whom nature has done least. There is no art which requires a greater combination of rare qualities, both of mind and person, than the histrionic, when truly; that is, ideally, considered. Except upon the occasions already stated, Mr. Forrest's Macbeth, as he now performs it, is a calm and stately, almost sculpturesque, piece of acting. In more level and rapid intonations, it is occasionally displeasing—that is, to English ears—from an Americanism of tone and accent, which, from their natural delivery, become distinguishable in such passages. But we must learn to pardon this, as a provincialism; and the actor will meantime learn to correct it, by a longer residence among us. Of the new business at which we have hinted, there are two pieces of physical effect one of which pleased and the other displeased us. On returning from the murder of Duncan, Macbeth stumbles, as it were, upon his lady unaware, and lifts his dagger to stab her, as if she were a stranger, or a spy upon his conduct. The situation was appalling, and admirably executed by both performers. It is natural, as well as effective. But in the instance against which we are about to remonstrate, thcre is a want of taste and discrimination. In the banquet scene, Mr. Forrest approaches the chair where the ghost of Banquo sits, blindly, and as if thinking of anything but "the graced person" of his invited guest; and then starts away in horror, as if the natural flesh and blood body were actually present. Now this is a false attempt at objectivity— an aim which perhaps the poet has already carried too far, by permitting the ghost to be visible at all, and deprives the scene of its right moral. The ghost of Banquo is but an incarnation of the terrors of Macbeth's conscience; because Fleance has fled, his "fit has come again." His mind once disturbed, loses self-control; the slightest trouble affects it, and destroys its balance. The actor should show this, and should intimate the subjective feeling of which the outward action is merely an index; and should prepare such action by previous intimation. We commend this to Mr. Forrest's consideration; and we hope that, as he must see that from our remarks we mean kindly towards him, he will accept the suggestion in good part, and attempt its adoption. In conclusion, we must not omit Lady Macbeth's somnolent scene. Some critics, affecting nicety where they wanted wisdom, have complained that Shakspeare has introduced this terrible catastrophe too abruptly; that he has neglected to mark the degrees by which Lady Macbeth’s mind fell into such an abject state. Such persons have never rightly apprehended the symbolic nature of the drama generally. They ought, to be consistent, to require that Macbeth should, in a set speech, tell his lady of "the air drawn dagger," in order to justify her allusion to it in the banquet scene. Great poets trust their readers' imagination; only little ones dream of exhausting their argument. The amount of action in this tra gedy necessitated a typical treatment of the subject. During the whole of the fourth act Lady Macbeth never appears—an interval which the reader or spectator readily fills up; and when the guilty woman's actual condition is related by her attendant, it is at once recognized for what might naturally, under the circumstances, have been expected. Miss Cushman acted this incident of horror with fearful energy. We should counsel her to a still slower movement: the impression it is calculated to produce, will be found to correspond to the time which it may reasonably be made to fill.

PRINCESS'S THEATRE.—Among the desiderata of the modern stage, the most urgent has long been a great actress—one capable of sustaining the gorgeous majesty of the tragic muse. Coarseness or feebleness of execution has marred the efforts, with one or two exceptions, of the best candidates for the vacant throne; and even if they be admitted as proficients in the last graces of histrionic art, the increasing number of theatres, and the consequent distribution of talent, demands additional competitors. It was, therefore, with much gratification that we heard that Mr. Macready had discovered, in America, a lady qualified for occupying the high places of the drama. Miss Cushman's appearance in the character of Bianca, we have already announced. We have now to do with her performance of Lady Macbeth. Here the powers of the actress are tested, as already those of the poet had been, to the utmost. A heroine so sublime and terrible, that the highest intellect and quickest imagination are blended in her character—a character simply but graphically suggested by Holin shed's Chronicle—a woman "very ambitious, burning in unquenchable desire to bear the name of queen;"— but elevated, by poetic genius, into a grandeur not to be excelled. Shakspeare [sic] starts in his tragedy from a high point—all is mountain land from the beginning. The regal ambition, the unquenchable desire, is a "foregone conclusion." Long before the action of the play, the lady had proposed to her husband that "suggestion whose horrid image" should afterwards "unfix his hair, and make his seated heart knock at his ribs against the use of nature;" the "thought, whose murder yet was but fantastical," was familiar to them both, long ere the Weird Sisters had hailed the successful warrior as "king hereafter;" else would it not have so readily occurred to his mind as the only means by which the crown was to be obtained; else upon the receipt of his letter had his "dearest partner of greatness" not at once conceived the design and plan of assassination. From the moment that Miss Cushman entered, we were convinced that she had grasped this leading idea: her reading of the letter was the finest thing we have lately seen upon the stage. No living actress has approached it. The scene with the attendant and her husband, together with the intervening soliloquies, were sustained with equal power: the lines—

Nor Heaven peep through the blanket of the dark, To cry, Hold! hold!

were given with terrific effect.Her interview with the king was managed with dignity; nor did her temptation of her husband lack proper emphasis. The greatness of these scenes makes it difficult to rise above them. Shakspeare however, has piled alps on alps, and in the mountainous region which he travels, every step we take is an ascending one. 'Tis weary climbing, but the mighty business of the time compels the labour. Miss Cushman sustained it vigorously: she is greater after the murder than before; every word breathed with a separate life; every sentence glowed with accumulated expression; every gesture added to the signification of the text; not only her hand and fingers pointed, but her entire arms were instinct with the meaning of every pas sage. Perhaps in all this there was an exuberance of power, a plenitude of New-World energy, much of which must be subdued—some of it utterly de stroyed—before the actress is consummated. All this is true. Taste may have much to object—may ultimately rescind and repeal much of this abundant action. Let it be so: let all such abatements be made, let all excesses be corrected—what then remains? Power, both mental and physical; that without which there is no art, nor possibility of any; power to conceive and to embody conception; the matériel which must precede cultivation, and alone gives it value. From not sufficiently considering this, critics fall into many errors. Mr. Edwin Forrest's acting is consequently liable to much misappreciation. We remember well when this gentleman first appeared, a distinguished actor expressed high expectations from what he had previously witnessed of Mr. Forrest in the United States: "He has," said he, "all the materials of a great actor about him." This was the generous tribute of praise bestowed by a rival artist. What, however, was the decision of the public arbiters of taste? They convicted the new actor of possessing "physical power:" they took him "in the manner." Undoubtedly, Mr. Forrest has great physical power; but does it therefore follow that he has not also mental power & At first, or at last, in all great sensible operations, physical force is needful; without it, execution must fall short of desire—with it, may exceed. Nothing less than the last exponent of mental power: it may, sometimes, appear more like a principal than an agent; but even then, it is a gift which makes him who possesses it a giant among men. We confess that we can admire an exhibition of physical force even for its own sake; but we are not prepared to assert that, in the instance of the actor before us, such force is not an exponent of mental power. The attempt to prove any such negative were simply ridiculous. Many of the objections we might take to Mr. Forrest's assumption of the character of Macbeth prove, indeed, the contrary. The business, for example, is in great part different from that usually adopted on the English stage; but always has an obvious reason, even when, from its novelty or other cause, it may awhile offend a taste which has been otherwise instructed. Much of the charge has, however, now fallen to the ground; for the actor's former manner has received considerable modification, and become mellowed with experience. He has learned that repose is the final grace of art, and has subdued all natural tendencies to violence, repressing his voice and action, except in the startling crises of the play, where both, without effort, spring forth with crushing effect; not because he is an actor who chooses thus to manifest strength, but because he is a strong man, and has simply liberated his energies. All this is merely a natural advantage—but it is an advantage, and must be reckoned among the natural qualifications of an actor, unless we hold that he is best fitted for the stage for whom nature has done least. There is no art which requires a greater combination of rare qualities, both of mind and person, than the histrionic, when truly; that is, ideally, considered. Except upon the occasions already stated, Mr. Forrest's Macbeth, as he now performs it, is a calm and stately, almost sculpturesque, piece of acting. In more level and rapid intonations, it is occasionally displeasing—that is, to English ears—from an Americanism of tone and accent, which, from their natural delivery, become distinguishable in such passages. But we must learn to pardon this, as a provincialism; and the actor will meantime learn to correct it, by a longer residence among us. Of the new business at which we have hinted, there are two pieces of physical effect one of which pleased and the other displeased us. On returning from the murder of Duncan, Macbeth stumbles, as it were, upon his lady unaware, and lifts his dagger to stab her, as if she were a stranger, or a spy upon his conduct. The situation was appalling, and admirably executed by both performers. It is natural, as well as effective. But in the instance against which we are about to remonstrate, thcre is a want of taste and discrimination. In the banquet scene, Mr. Forrest approaches the chair where the ghost of Banquo sits, blindly, and as if thinking of anything but "the graced person" of his invited guest; and then starts away in horror, as if the natural flesh and blood body were actually present. Now this is a false attempt at objectivity— an aim which perhaps the poet has already carried too far, by permitting the ghost to be visible at all, and deprives the scene of its right moral. The ghost of Banquo is but an incarnation of the terrors of Macbeth's conscience; because Fleance has fled, his "fit has come again." His mind once disturbed, loses self-control; the slightest trouble affects it, and destroys its balance. The actor should show this, and should intimate the subjective feeling of which the outward action is merely an index; and should prepare such action by previous intimation. We commend this to Mr. Forrest's consideration; and we hope that, as he must see that from our remarks we mean kindly towards him, he will accept the suggestion in good part, and attempt its adoption. In conclusion, we must not omit Lady Macbeth's somnolent scene. Some critics, affecting nicety where they wanted wisdom, have complained that Shakspeare has introduced this terrible catastrophe too abruptly; that he has neglected to mark the degrees by which Lady Macbeth’s mind fell into such an abject state. Such persons have never rightly apprehended the symbolic nature of the drama generally. They ought, to be consistent, to require that Macbeth should, in a set speech, tell his lady of "the air drawn dagger," in order to justify her allusion to it in the banquet scene. Great poets trust their readers' imagination; only little ones dream of exhausting their argument. The amount of action in this tra gedy necessitated a typical treatment of the subject. During the whole of the fourth act Lady Macbeth never appears—an interval which the reader or spectator readily fills up; and when the guilty woman's actual condition is related by her attendant, it is at once recognized for what might naturally, under the circumstances, have been expected. Miss Cushman acted this incident of horror with fearful energy. We should counsel her to a still slower movement: the impression it is calculated to produce, will be found to correspond to the time which it may reasonably be made to fill.

March 8, 1845:

PRINCESS'S THEATRE.–For the same actress to succeed eminently in Lady Macbeth and in Rosalind, is a test of diversity of power which few could endure uninjured. The play of “As You Like It," ranks as one of a class, the peculiar growth of an age. Lodge's Rosalynd was pedantic and prolix, and inflated with those conceits which beset the romances of the period. Nothing better shows Shakspeare's [sic] genius than the skill with which in his dramatic adaptations he preserved the spirit of such novels, and yet to a remark able degree avoided their turgidity and tediousness. His taste and judgment were equal to his genius– this, which was sometime a paradox, is now an ad mitted truism. It applies, however, not only to Shakspeare [sic] but to every great poet. It is a principle. For the euphuism of Lodge, Shakspeare [sic] wisely substituted an idealism of his own. The ideal quality of this entire play has been heretofore demon strated [see Athen., Nos. 872,873,874];—the writer, moreover, animadverted on the mistaken custom of the stage in casting its heroine to the comic actress, as if mirth and volatile wit, not passion and imagination, were the basis of the character. The mere assumption of such a part therefore by a tragic performer like Miss Cushman, is an improvement which, though evidently accidental, may tell advantageously for the cause of the drama. There is of necessity a severity in this lady's treatment of the character which preserves the classic outline, and the mirth is naturally of that enforced kind which the poet doubtless intended. Earnest, unfortunate, exiled; a princess beautiful and dignified of person, rich in mental endowments, inspired by love, but relieved from restraint, and made free of forest life; Rosalind is placed in a position to display, without reserve or disguise, whatever might be in her heart and mind, and manifests a benevolence of disposition, and a superiority of intellectual power, above suspicion and equal to all occasions. We regret, in such instances as the present, that histrionic talent should be compelled by theatrical management to drudge through the commonstage-version of such dramas, and thereby induced to adopt the ordinary stage-conception of such a part; and we impatiently await a better period when the regulation of the stage shall be under more intelligent guidance. Making allowance for the present evil state of matters, nothing could be more complete than Miss Cushman's execution. The decision, sharpness, and brilliancy of her style are admirable, and altogether unlike the doubtful manner of most performers. Her perception is clear and certain, and of her meaning, accordingly, no mistake is possible; hence her acting is, at all times, full of significance, force, and effect. Sometimes, perhaps, there is a tendency to masculine energy and vehemence; nevertheless, we were not unfrequently touched with a tenderness which seemed truly Shakspearian [sic]; and all through met with more vivacity and spiritual buoyancy than we had hoped for. Against the bar barous introduction of the cuckoo song we have already protested [see No. 874], and therefore can not consistently approve of it now; but as indicating the range of expression of which the new actress is capable, it merits mention. By the aid of gesture, expression, and management, Miss Cushman contrived to make a very limited vocal organ exceedingly effective. Soon it is to be wished that her manifest genius will put her into a position, where her own judgment will be permitted to decide in favour of dramatic purity. We cannot demand it at present —that is, of her—though of the manager we do—and that immediately. Suffice it now to say, that while in variety, delicacy, and sensibility, Miss Cushman's Rosalind is inferior to none, in force and depth it is perhaps without a rival. We venture, however, to recommend to her, a re-study of the character, in order to bring out its ideal, "heavenly," purity, which the general stage-conception not only omits but con troverts. And not only in this, but in all instances, she will act wisely by elevating her aim so as to grasp the moral and the ideal of Shakspearian [sic] characters, which in nearly every case is opposed to theatrical convention. In this manner Miss Cushman will deservedly win a reputation for originality, and confirm the expectations which from her natural power and evident talent, we are justified in entertaining of her future excellence. She has at least daring, determination, and purpose, to begin with, and these properly governed will lead to permanent success. On Tuesday Miss Cushman appeared in the character of Mrs. Haller, and showed originality of conception in the preservation of quiet penitence throughout, which touched in the audience "the source of sympathetic tears." But we cannot afford to dwell long on any part in such a play as "The Stranger." It is by the use of the Shakspearian [sic] bow that histrionic vigour must be tested. On Thursday 'Lear' was produced,—not Shakspeare's [sic], but that alteration of Tate's alteration, which the stage, since Edmund Kean's time, has presented as a miserable compromise—so little influence have even the reforms of Mr. Macready retained on theatrical practice. After the representation of the restored 'Lear' at Covent Garden, no manager of any respectability should have insulted public taste with a corrupted version. The audience, however, came to see the actor, not the play. Whatever doubts we might have entertained as to Mr. Forrest's powers in Macbeth, they are all dissipated by his performance of Lear. Every natural advantage, in this character, comes to the actor's aid. His person is regal; his countenance, full of grandeur, looks like a cast from the antique ; he moves, as it were, the image of Paternal Majesty. In all this, however, it is not the actor's conception, but nature's own magnificent work in his personal conforma tion, which awes and impresses the spectator. The actor himself is more solicitous about the huma nities of his assumption; he takes on the trembling appearance of age from the beginning, and manifests it, to our thinking, in excess. The artist should rather suggest than exhaust. But with this one, all objections vanish. From the moment that the king descends from his throne and addresses Cordelia, Mr. Forrest engaged and retained the sympathies of the house. The impetuosity, resentment, rage, wender, disappointment, spleen, indignation, despair, madness, recovery, and death of the injured monarch were successfully pourtrayed with a breadth and depth of effect which,while they electrified thegeneralaudience, were calculated to satisfy the judgment of the more critical. What particularly distinguishes Mr. Forrest's performance of this sublime impersonation is, the equability with which he sustains it through the whole series of developements. There were no fits, nor starts, nor spasmodic convulsions ; no violent heavings, no mannerisms, no affectations to mar the uniform grandeur of the scene. The fearful male diction on Goneril lost nothing of its fearfulness by Mr. Forrest's delivery; it was, in fact, overwhelming.

PRINCESS'S THEATRE.–For the same actress to succeed eminently in Lady Macbeth and in Rosalind, is a test of diversity of power which few could endure uninjured. The play of “As You Like It," ranks as one of a class, the peculiar growth of an age. Lodge's Rosalynd was pedantic and prolix, and inflated with those conceits which beset the romances of the period. Nothing better shows Shakspeare's [sic] genius than the skill with which in his dramatic adaptations he preserved the spirit of such novels, and yet to a remark able degree avoided their turgidity and tediousness. His taste and judgment were equal to his genius– this, which was sometime a paradox, is now an ad mitted truism. It applies, however, not only to Shakspeare [sic] but to every great poet. It is a principle. For the euphuism of Lodge, Shakspeare [sic] wisely substituted an idealism of his own. The ideal quality of this entire play has been heretofore demon strated [see Athen., Nos. 872,873,874];—the writer, moreover, animadverted on the mistaken custom of the stage in casting its heroine to the comic actress, as if mirth and volatile wit, not passion and imagination, were the basis of the character. The mere assumption of such a part therefore by a tragic performer like Miss Cushman, is an improvement which, though evidently accidental, may tell advantageously for the cause of the drama. There is of necessity a severity in this lady's treatment of the character which preserves the classic outline, and the mirth is naturally of that enforced kind which the poet doubtless intended. Earnest, unfortunate, exiled; a princess beautiful and dignified of person, rich in mental endowments, inspired by love, but relieved from restraint, and made free of forest life; Rosalind is placed in a position to display, without reserve or disguise, whatever might be in her heart and mind, and manifests a benevolence of disposition, and a superiority of intellectual power, above suspicion and equal to all occasions. We regret, in such instances as the present, that histrionic talent should be compelled by theatrical management to drudge through the commonstage-version of such dramas, and thereby induced to adopt the ordinary stage-conception of such a part; and we impatiently await a better period when the regulation of the stage shall be under more intelligent guidance. Making allowance for the present evil state of matters, nothing could be more complete than Miss Cushman's execution. The decision, sharpness, and brilliancy of her style are admirable, and altogether unlike the doubtful manner of most performers. Her perception is clear and certain, and of her meaning, accordingly, no mistake is possible; hence her acting is, at all times, full of significance, force, and effect. Sometimes, perhaps, there is a tendency to masculine energy and vehemence; nevertheless, we were not unfrequently touched with a tenderness which seemed truly Shakspearian [sic]; and all through met with more vivacity and spiritual buoyancy than we had hoped for. Against the bar barous introduction of the cuckoo song we have already protested [see No. 874], and therefore can not consistently approve of it now; but as indicating the range of expression of which the new actress is capable, it merits mention. By the aid of gesture, expression, and management, Miss Cushman contrived to make a very limited vocal organ exceedingly effective. Soon it is to be wished that her manifest genius will put her into a position, where her own judgment will be permitted to decide in favour of dramatic purity. We cannot demand it at present —that is, of her—though of the manager we do—and that immediately. Suffice it now to say, that while in variety, delicacy, and sensibility, Miss Cushman's Rosalind is inferior to none, in force and depth it is perhaps without a rival. We venture, however, to recommend to her, a re-study of the character, in order to bring out its ideal, "heavenly," purity, which the general stage-conception not only omits but con troverts. And not only in this, but in all instances, she will act wisely by elevating her aim so as to grasp the moral and the ideal of Shakspearian [sic] characters, which in nearly every case is opposed to theatrical convention. In this manner Miss Cushman will deservedly win a reputation for originality, and confirm the expectations which from her natural power and evident talent, we are justified in entertaining of her future excellence. She has at least daring, determination, and purpose, to begin with, and these properly governed will lead to permanent success. On Tuesday Miss Cushman appeared in the character of Mrs. Haller, and showed originality of conception in the preservation of quiet penitence throughout, which touched in the audience "the source of sympathetic tears." But we cannot afford to dwell long on any part in such a play as "The Stranger." It is by the use of the Shakspearian [sic] bow that histrionic vigour must be tested. On Thursday 'Lear' was produced,—not Shakspeare's [sic], but that alteration of Tate's alteration, which the stage, since Edmund Kean's time, has presented as a miserable compromise—so little influence have even the reforms of Mr. Macready retained on theatrical practice. After the representation of the restored 'Lear' at Covent Garden, no manager of any respectability should have insulted public taste with a corrupted version. The audience, however, came to see the actor, not the play. Whatever doubts we might have entertained as to Mr. Forrest's powers in Macbeth, they are all dissipated by his performance of Lear. Every natural advantage, in this character, comes to the actor's aid. His person is regal; his countenance, full of grandeur, looks like a cast from the antique ; he moves, as it were, the image of Paternal Majesty. In all this, however, it is not the actor's conception, but nature's own magnificent work in his personal conforma tion, which awes and impresses the spectator. The actor himself is more solicitous about the huma nities of his assumption; he takes on the trembling appearance of age from the beginning, and manifests it, to our thinking, in excess. The artist should rather suggest than exhaust. But with this one, all objections vanish. From the moment that the king descends from his throne and addresses Cordelia, Mr. Forrest engaged and retained the sympathies of the house. The impetuosity, resentment, rage, wender, disappointment, spleen, indignation, despair, madness, recovery, and death of the injured monarch were successfully pourtrayed with a breadth and depth of effect which,while they electrified thegeneralaudience, were calculated to satisfy the judgment of the more critical. What particularly distinguishes Mr. Forrest's performance of this sublime impersonation is, the equability with which he sustains it through the whole series of developements. There were no fits, nor starts, nor spasmodic convulsions ; no violent heavings, no mannerisms, no affectations to mar the uniform grandeur of the scene. The fearful male diction on Goneril lost nothing of its fearfulness by Mr. Forrest's delivery; it was, in fact, overwhelming.

April 5, 1845:

The most elegant and witty of Shakspeare's come dies, 'Much Ado About Nothing,' was produced on Thursday evening, to give Miss Cushman an opportunity of appearing as the representative of Beatrice. Little indebted to the Spanish romance from which he derived the serious part of his plot, the poet mainly depended on the original comic characters with which his unaided genus has enriched and varied the scenes in its dramatic developement. Failing or not caring to excite strongly our interest for Hero and her lover, Shakspeare succeeded to ad miration in so depicting the creatures of his own fancy, Benedick and Beatrice, Dogberry and Verges, as to charm us with the vivacity and raillery, the humour and absurdity of the dialogues and incidents in which they partake, and of which we know not whether to prefer the brilliancy and ingenuity, or the kindliness and bonhomie. Benedick and Beatrice are in particular beautiful creations; imaginary haters of marriage, because the theme has become the ordinary topic of their satire ; their similarity is made most philosophically the ground of an apparent antagonism, and thus opportunity given for a wit-combat between the friendly litigants, equally remarkable for its inveteracy and good humour. The absence of all bitterness prepares us for the final reconciliation of the parties; and we should be, indeed, disappointed if two amiable, though somewhat perverse beings, so well matched in disposition and feeling, were not at last made happy in that union, which it is from the first evident they only affect to despise. Accomplished, generous, brave, and virtuous, both enlist from the beginning the best sympathies in their favour; we wish them well throughout their merry trial—the dash of earnestness that at length comes over it, serves but to deepen and confirm the interest already excited—and we cannot help rejoicing in their ultimate triumph, as that of two eccentric companions who have made themselves unexpectedly agreeable, on a short excursion in which there has been more of sunshine than of shade—some few minutes of cloud only to as many hours of delightful enjoyment. The manner in which this play, like others, has been revived at this theatre, does no credit to the management; the scenery and appointments being execrable, and the performers turned loose on the stage without sufficient rehearsal. Only the four pure Shaksperian [sic] characters, Benedick (Mr. Wallack), Beatrice (Miss Cushman), Dogberry (Mr. Compton), and Verges (Mr. Oxberry), have escaped without serious injury; but these could not be now better performed anywhere. Mr. Wallack is the only actor left on the metropolitan boards who has the slightest pretension to enact the gentleman of comedy; and Miss Cushman showed her usual decision and purpose in the assumption of the character of Beatrice—qualities in which, at present, she has not only no rival, but no competitor. Her acting, notwithstanding some too obvious mannerism, was spirited, overflowing with mirth, yet chaste, marked with maidenly reserve, and even in the very riot of wit or humour not overstepping the limits of good manners. These merits are rare, and indicate so much judgment in the actress, that, with her talents, we have no doubt of the continuance, and even increase, of her popularity. It would be superfluous to praise either Mr. Compton or Mr. Oxberry: the former gentleman is the most classic of low comedians, and must be seen to be appreciated. For the rest, as we have intimated, silence is mercy; but the want of control and regulation—nay, even of ordinary care—in the production of the legitimate drama at this sometime operatic theatre is an experi ment on the patience of an English audience, which almost deserves laudation for its hardy audacity and reckless daring.

The most elegant and witty of Shakspeare's come dies, 'Much Ado About Nothing,' was produced on Thursday evening, to give Miss Cushman an opportunity of appearing as the representative of Beatrice. Little indebted to the Spanish romance from which he derived the serious part of his plot, the poet mainly depended on the original comic characters with which his unaided genus has enriched and varied the scenes in its dramatic developement. Failing or not caring to excite strongly our interest for Hero and her lover, Shakspeare succeeded to ad miration in so depicting the creatures of his own fancy, Benedick and Beatrice, Dogberry and Verges, as to charm us with the vivacity and raillery, the humour and absurdity of the dialogues and incidents in which they partake, and of which we know not whether to prefer the brilliancy and ingenuity, or the kindliness and bonhomie. Benedick and Beatrice are in particular beautiful creations; imaginary haters of marriage, because the theme has become the ordinary topic of their satire ; their similarity is made most philosophically the ground of an apparent antagonism, and thus opportunity given for a wit-combat between the friendly litigants, equally remarkable for its inveteracy and good humour. The absence of all bitterness prepares us for the final reconciliation of the parties; and we should be, indeed, disappointed if two amiable, though somewhat perverse beings, so well matched in disposition and feeling, were not at last made happy in that union, which it is from the first evident they only affect to despise. Accomplished, generous, brave, and virtuous, both enlist from the beginning the best sympathies in their favour; we wish them well throughout their merry trial—the dash of earnestness that at length comes over it, serves but to deepen and confirm the interest already excited—and we cannot help rejoicing in their ultimate triumph, as that of two eccentric companions who have made themselves unexpectedly agreeable, on a short excursion in which there has been more of sunshine than of shade—some few minutes of cloud only to as many hours of delightful enjoyment. The manner in which this play, like others, has been revived at this theatre, does no credit to the management; the scenery and appointments being execrable, and the performers turned loose on the stage without sufficient rehearsal. Only the four pure Shaksperian [sic] characters, Benedick (Mr. Wallack), Beatrice (Miss Cushman), Dogberry (Mr. Compton), and Verges (Mr. Oxberry), have escaped without serious injury; but these could not be now better performed anywhere. Mr. Wallack is the only actor left on the metropolitan boards who has the slightest pretension to enact the gentleman of comedy; and Miss Cushman showed her usual decision and purpose in the assumption of the character of Beatrice—qualities in which, at present, she has not only no rival, but no competitor. Her acting, notwithstanding some too obvious mannerism, was spirited, overflowing with mirth, yet chaste, marked with maidenly reserve, and even in the very riot of wit or humour not overstepping the limits of good manners. These merits are rare, and indicate so much judgment in the actress, that, with her talents, we have no doubt of the continuance, and even increase, of her popularity. It would be superfluous to praise either Mr. Compton or Mr. Oxberry: the former gentleman is the most classic of low comedians, and must be seen to be appreciated. For the rest, as we have intimated, silence is mercy; but the want of control and regulation—nay, even of ordinary care—in the production of the legitimate drama at this sometime operatic theatre is an experi ment on the patience of an English audience, which almost deserves laudation for its hardy audacity and reckless daring.

May 3, 1845:

PRINCESS'S.-A new five-act play has, also, been produced here. It is the production of Mr. James Kenney, now a veteran member of the dramatic guild; and is called 'Infatuation.' [...] The “"nfatuated" lady was performed by Miss Cushman, who verily laboured hard to give animation and interest to a part void of every quality for conciliating the sympathies of a British audience. The performance was, as might have been expected, barely tolerated, and the applause, on its re-announcement, was exceedingly limited and partial.

PRINCESS'S.-A new five-act play has, also, been produced here. It is the production of Mr. James Kenney, now a veteran member of the dramatic guild; and is called 'Infatuation.' [...] The “"nfatuated" lady was performed by Miss Cushman, who verily laboured hard to give animation and interest to a part void of every quality for conciliating the sympathies of a British audience. The performance was, as might have been expected, barely tolerated, and the applause, on its re-announcement, was exceedingly limited and partial.

May 31, 1845:

PRINCESS'S THEATRE –Tobin's comedy of 'The Honeymoon' has been produced at this theatre for the purpose of trying Miss Cushman in Juliana. This play is one of many illustrating the kind of management to which theatres are ordinarily subject. Suppressed until after the author's death, this elegant drama was originally produced under the direction of the performers alone, and received from them the present arrangement of the stage-business. In order ing this important matter, it seems to have been taken for granted, that the characters are all copies of well-known originals in Shakspeare’s 'Taming of the Shrew' and 'Twelfth Night'; and, therefore, that the part of Duke Aranza was the double, though in a tamer mood, of plain Petruchio. A slight examination, however, of Tobin's comedy will satisfy any critic that there are designed differences in every apparent copy; none, however, so great as in Duke Aranza himself, who is evidently intended by the poet to be, not the duplicate, but the very opposite of Petruchio-polite where he was boisterous, refined and gentle where he was rude and violent. The players, however, thought otherwise, and accordingly, when introducing the bride to the humble cottage which was to be her home, directed that the Duke should "bring a chair forward and sit down"—leaving the lady to stand, and look around her. Now, the dia logue of the sceneshows the precise contrary intention in the poet's mind. It is evident that with more than courtesy—even with yeoman humility—the Duke should, in the most respectful manner, hand the chair to his wife, and that she should remain seated,until urged to exclaim—"I will go home." Not until necessity arises should the Duke assume any vehemence of authority, and then no more than befits his station. Not by violence, but by kindness, should he subdue the fantastic lady's proud and stubborn disposition. This is the spirit of the character, and indeed breaks through, notwithstanding the conventional error made by every actor in the part. Speedily, then, should the stagedirections be reformed, to prevent the further continuance of a mistake, which, though it does not ruin, mars the consistency of one of the finest per sonations. The correction, too, would much improve the effect of Juliana's performance in the second act, and for the lady's sake should be at once adopted. The manner in which Miss Cushman went through the character increased our esteem for her. She was more intent on subduing what was bizarre in the situations, than in exaggerating any point; and showed her capacity to be quiet and natural—nay, studiously so—in parts requiring rather comic vivacity than tragic force. Never wanting in discrimination, she nevertheless was throughout animated and spirited —and it gives us much pleasure to record that this lady's attractions show yet no signs of diminution. The housestill fills, though the management perseveres in paying the smallest possible attention to the mise en scène,and so distributing the inferior characters as justly to excite public ridicule. This is not only putting the actress to an unfair test, but scarcely making a proper return for the patronage which has been so liberally awarded.

PRINCESS'S THEATRE –Tobin's comedy of 'The Honeymoon' has been produced at this theatre for the purpose of trying Miss Cushman in Juliana. This play is one of many illustrating the kind of management to which theatres are ordinarily subject. Suppressed until after the author's death, this elegant drama was originally produced under the direction of the performers alone, and received from them the present arrangement of the stage-business. In order ing this important matter, it seems to have been taken for granted, that the characters are all copies of well-known originals in Shakspeare’s 'Taming of the Shrew' and 'Twelfth Night'; and, therefore, that the part of Duke Aranza was the double, though in a tamer mood, of plain Petruchio. A slight examination, however, of Tobin's comedy will satisfy any critic that there are designed differences in every apparent copy; none, however, so great as in Duke Aranza himself, who is evidently intended by the poet to be, not the duplicate, but the very opposite of Petruchio-polite where he was boisterous, refined and gentle where he was rude and violent. The players, however, thought otherwise, and accordingly, when introducing the bride to the humble cottage which was to be her home, directed that the Duke should "bring a chair forward and sit down"—leaving the lady to stand, and look around her. Now, the dia logue of the sceneshows the precise contrary intention in the poet's mind. It is evident that with more than courtesy—even with yeoman humility—the Duke should, in the most respectful manner, hand the chair to his wife, and that she should remain seated,until urged to exclaim—"I will go home." Not until necessity arises should the Duke assume any vehemence of authority, and then no more than befits his station. Not by violence, but by kindness, should he subdue the fantastic lady's proud and stubborn disposition. This is the spirit of the character, and indeed breaks through, notwithstanding the conventional error made by every actor in the part. Speedily, then, should the stagedirections be reformed, to prevent the further continuance of a mistake, which, though it does not ruin, mars the consistency of one of the finest per sonations. The correction, too, would much improve the effect of Juliana's performance in the second act, and for the lady's sake should be at once adopted. The manner in which Miss Cushman went through the character increased our esteem for her. She was more intent on subduing what was bizarre in the situations, than in exaggerating any point; and showed her capacity to be quiet and natural—nay, studiously so—in parts requiring rather comic vivacity than tragic force. Never wanting in discrimination, she nevertheless was throughout animated and spirited —and it gives us much pleasure to record that this lady's attractions show yet no signs of diminution. The housestill fills, though the management perseveres in paying the smallest possible attention to the mise en scène,and so distributing the inferior characters as justly to excite public ridicule. This is not only putting the actress to an unfair test, but scarcely making a proper return for the patronage which has been so liberally awarded.

June 1, 1845:

PRINCESS'S.—'The Merchant of Venice' and 'Guy Mannering' have been revived at this theatre, to exhibit Miss Cushman in Portia and Meg Merrilies. The first is a fine performance; the last, one of fearful and picturesque energy, which must make a great impression. Let this lady, however, beware of melo dramatic characters. The manner in which plays are put on the stage and the minor characters filled at this theatre continues to be disgraceful.

PRINCESS'S.—'The Merchant of Venice' and 'Guy Mannering' have been revived at this theatre, to exhibit Miss Cushman in Portia and Meg Merrilies. The first is a fine performance; the last, one of fearful and picturesque energy, which must make a great impression. Let this lady, however, beware of melo dramatic characters. The manner in which plays are put on the stage and the minor characters filled at this theatre continues to be disgraceful.

June 21, 1845:

PRINCESS'S.—The revival at this theatre of Mr. Knowles's touching play of 'The Wife,' has tested Miss Cushman in another new character, that of the much tried, but at last triumphant, Mariana. With all her usual discrimination and force, Miss Cushman exhibited more pathos and tenderness than we have yet witnessed in the part. Mr. Wallack's St. Pierre, also, was of great merit, having a dash and vigour seldom equalled. Were more care and judgment shown in regard to the mise en scène at this theatre, it might, with such performers, command extraordinary success. The manager seems to have no faith in the proverb, "There is that which scat tereth and yet gathereth." But there are few the atrical directors who have the wisdom of Solomon.

PRINCESS'S.—The revival at this theatre of Mr. Knowles's touching play of 'The Wife,' has tested Miss Cushman in another new character, that of the much tried, but at last triumphant, Mariana. With all her usual discrimination and force, Miss Cushman exhibited more pathos and tenderness than we have yet witnessed in the part. Mr. Wallack's St. Pierre, also, was of great merit, having a dash and vigour seldom equalled. Were more care and judgment shown in regard to the mise en scène at this theatre, it might, with such performers, command extraordinary success. The manager seems to have no faith in the proverb, "There is that which scat tereth and yet gathereth." But there are few the atrical directors who have the wisdom of Solomon.

Provenance

Hathi Trust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.50182593

Location

London, UK

Geocode (Latitude)

51.5073219

Geocode (Longitude)

-0.1276474

Social Bookmarking

Geolocation

Collection

Citation

“Athenaeum, Cushman Mentions, Jan-June 1845 (Vol. 1),” Archival Gossip Collection, accessed April 19, 2024, https://www.archivalgossip.com/collection/items/show/473.