Working with or Deciphering Archival Documents

Dever et al. point out that the demonizing of gaps in archival research nurtures the illusion of some kind of coherent history that can be discovered:

The challenge […] becomes one of how to read and work with these fragments, given that, as researchers, ‘we are generally dismayed by the gaps that fragments expose, and try to fill them’. We often harbour an insistent (deeply suppressed and often denied) desire to find in our archival sources a whole where there can only ever be random parts, to perform acts of reconstitution in the service of producing a coherent and seamless account of our subject. […] How, then, do we live with – and work with – the patterns of knowing and not knowing thrown up by these sources … .

(Dever et al. 100–01)

It is tough to cast this urge to find the ‘truth’ (the ‘full historical truth’) aside, since it is difficult to accept that we may never know it or, in fact, that there was never such a truth. What researchers can achieve, however, is a process of sense-making of fragments in the archives, which gives a voice to often forgotten historical agents and presents new perspectives on historical events, lives, and constellations. This being said, do not let me deceive you, it is an ongoing struggle to happily coexist with the fragments. How often have we desperately hoped for a historical document that explains it all to magically pop up? Too many times. How often will that happen again in the next months? Way too often. Sometimes, we were successful and it is those times that stick with us. They keep us going to dig deeper. In doing so, we were facing several issues of working with and deciphering archival documents.

Readability and Transcription Issues

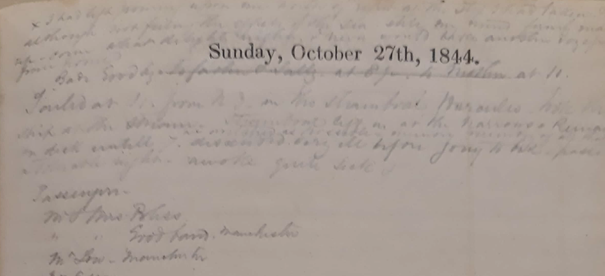

A prime example would be Cushman’s sole (known) diary (currently held at Columbia University in NYC.Cushman wrote these entries in in the 1840s with pencil and often in great distress as she sailed from the US to England. The archival documents are often stored in folders and researchers are not required to wear gloves, which has likely contributed to the fading of her writing over time.

Emma Stebbins, Charlotte Cushman’s longtime partner and ‘wife’ (Cushman called drew attention to the illegibility of Cushman’s diary entries in 1876.

Mrs. Cushman brought me some materials to look over – among them a diary of C.C.’s own[?] – written before and after her arrival in England in 1845 – not extending much over a year – and so finely written in pencil that I could only decipher it with a magnifying class! – no letters yet – Mrs. C. must first go over them herself, and each one of them is so long and so finely written that it would take an hour to go over it –

(Letter from Emma Stebbins to Sidney Lanier, June 6, 1876)

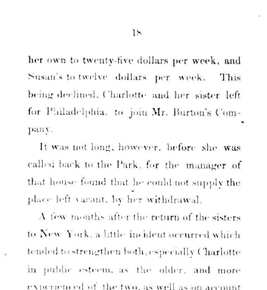

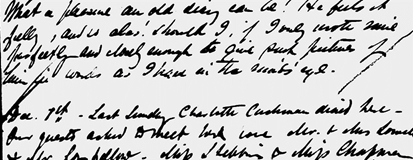

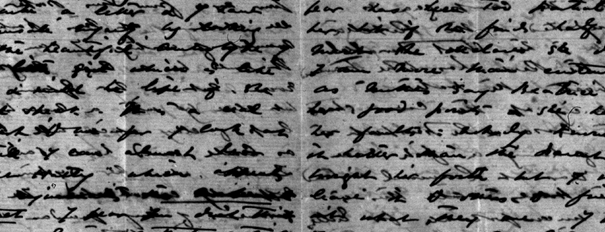

In the 21st century, additional problems occur: deciphering historical forms of handwriting, a lack of preservation practices, incomplete or wrongly linked document pages, etc. Low-quality microfilm editions of 19th century letters or monographs also impede OCR. Below, you can find a page from Walker’s Reminiscences (1876), a screenshot of Annie Fields diary from 1871, and a screenshot of a letter from Schlesinger collection of Harriet Hosmer correspondence (microfilm, Schlesinger Library, A-162, box 94):

Additionally, preservation and knowledge management practices can interfere with transcription attempts. For several CCP letters, the archive used non-transparent tape to secure the letter pages in the folders. For some instances, the tape might be unproblematic because the missing letters or words can be inferred from the context; however, for names or whole passage that are hard to read, the tape may inhibit understanding.

Historical Agents Concealing and Destructing Information

Indeed, the notion that coherent and legible revelations of feelings will inevitably emerge from sifting through the archival remains of intimate attachments is questionable, not least because more telling documents have often failed to survive. We must contend with ellipsis, code and impenetrable innuendo in a context where, unlike the original recipients, as readers we lack the shared context that would guarantee comprehension of so many details in the documents we examine.

(Dever et al. 122–23)

Many hours, we spent wondering where and why the documents had been archived in those bundles the way that they can be found nowadays. The lack of information regarding provenance is remarkable and intriguing since the letters explicitly state the desire to keep certain parts of Cushman’s private life a secret to protect her public image and maintain her respectability (Please visit Dr. Katrin Horn’s blog entry on the provenance of the Charlotte Cushman Papers in the Library of Congress for more information).

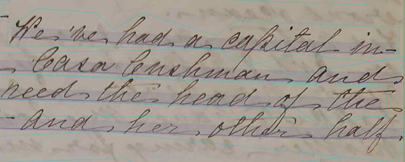

Even though the documents speak to delicate issues of jealousy, for instance, the above-mentioned quote from Emma Stebbins’s letter indicates that Mrs. C. (Emma Crow Cushman, married to Cushman’s nephew and longtime love of Cushman herself) had apparently still kept many letters among which can be found very intimate accounts. Cushman repeatedly advised Emma to be careful with the letters. Cushman was concerned about her public image and and tried to prevent her relationship and intimate details from being exposed publicly (e.g. Letter from Charlotte Cushman to Emma Crow, Sep 12, 1860). From Cushman’s perspective, her romantic relationships to women interfered with the public image that she aspired to. To avoid the exposure of her romantic relationships to women, Charlotte Cushman advised her correspondents to destroy letters or emphasized that she would do it herself, such as was the case in a letter to Emma Crow, June 30, [1858]. In another letter from Charlotte Cushman to Emma Crow, March 31, 1858, Charlotte writes

Bless you my child for all your love for me. which you express so naively. […] For coming to the Hotel to sleep with me. darling. I think if I were your Papa or Mama. I should be sorry to refuse you – but I should be sorry to have you do such a thing. I need not assure you of the true pleasure it would be to me. your own heart which tells you that you are dear to me. will speak for me. if you doubt that I want you [both words underlined]. and if I were on a visit to your house [inserted] I would open my arms gladly to such a visitee. & you should talk to me & keep me awake all nights if you would. but I dont like my “pretty white bird” coming to the Hotel to sleep. […] & when I come. if I do sleep with you. I will cut off one of your curls as you lay sleeping by my side. I will kiss you further pretty thought of getting me a little picture of you.

(LoC, CCP, 1:60-61)

This paragraph is solely an excerpt from a bulk of letters that were luckily preserved. Other correspondents included in the Omeka collection on our website also used to destroy letters revolving around or addressing Charlotte Cushman, such as Byron Smith.

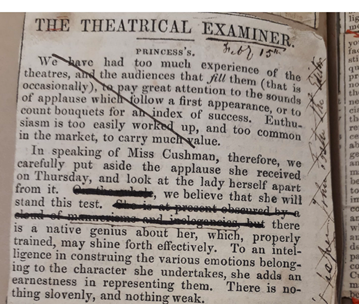

Other examples of ‘redacted information’ give us an idea of what Charlotte Cushman would have liked to conceal but was not successful in keeping from the public. She (assuming that the one adding notes in black ink to the article below was Cushman) repeatedly crossed out all the negative aspects of the review of her performance, e.g.: “She is at present obscured by a cloud of mannerisms and inelegancies, but” and “But the actress has much to learn and unlearn?.” These instances give us an idea of what Cushman approved of and which comments she would have preferred to hide from the public. The annotations suggest that she was invested in actively tracing and shaping her public image, and they help researchers fill the gaps. These kind of sources stress the invaluable significance of archival access since the articles may be accessible online via databases but the handwritten annotations are not.

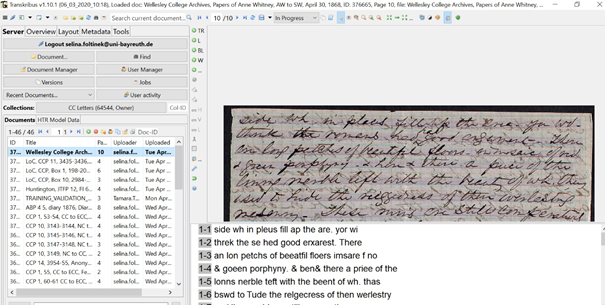

Transkribus: Technical Restraints

As indicated in the Annotation and User Guidelines, the project is working with Transkribus to transcribe the handwritten archival documents of various archives. Transkribus is a software developed by the READ project (Recognition and Enrichment of Archival Documents) to automatically recognize and transcribe archival documents.[1] Different styles of handwriting (Charlotte Cushman, Wayman Crow, Kate Field, Emma Stebbins, etc.) present a challenge to our ambition of being able to transcribe the archival documents automatically. We have to train our transcription model with more data than expected before getting reliable results that do not require too many corrections. Below, I have attached an example of Kate Field letters. In contrast to other authors that we use letters of for our research purposes, Field added some peculiar ‘tails’ to the final letters of a word. Our trained Transkribus’s model identifies the ‘tails’ as letters which then requires us to interfere and delete single letters at the end of almost all words.

Ink bleeding through the pages is another major obstacle in the transcription process since words of the reverse page show. In general, the quality of scans is of utmost importance as indicated above. Below, you can see a screenshot to visualize an instance for which the program failed to transcribe the relevant letter page.

Further problems arise when the document is partly damaged, artificially held together, or when words are written above/across other words.

Transcribing names is especially challenging if they have not surfaced beforehand. A google search of different spelling options in combination with Charlotte Cushman does the job most of the time.

The quality of the handwriting differs from document to document and depends on paper quality as well as on the time and (physical and mental) constitution that the letter was written in. For instance, Cushman’s letters to her mother are most often very symmetrical, whereas letters to Emma Crow were often hastily written, as Cushman wrote to her very often and told her about the busy life of an actress. She mirrors her distress and anxiety in irregular handwriting, confusing punctuation, e.g. the random use of full stops/dots (sometimes instead of commas but not always), or misspelt, erased, and missing words.[2] It proves to be particularly difficult to differentiate between a/A, c/C, r/e, en/e. Martin Prell explains that CERs (Character Error Rates) between 3% (gothic book scripts from the 13th and 14th century) and 5% (handwriting of Jeremy Bentham’s secretaries, 18th century, English) can be reached (2). However, given the nature of our project we cannot reach a CER below 10% at the moment, since we have documents from a wide range of people with different types of handwriting.[3] Additionally, private letters and diary entries often do not show a clear handwriting and differ from handwriting addressed to a wider public. Hence, even the handwriting of a single person can look dramatically different across multiple documents.

(author: Selina Foltinek)

[1] There is also a lite version available that is browser-based.

[2] Prell lists similar issues for his project about handwriting from the 18th century (2).

[3] Prell explains that the CER is significantly affected when more than five different types of handwriting are used for the analysis (8).

Works Cited

Dever, Maryanne, et al. “The Intimate Archive.” Archives and Manuscripts, vol. 38, no. 1, May 2010, pp. 94–137.

Horn, Katrin. “An Intimate Knowledge of the Past? Gossip in the Archives,” History of Knowledge, February 12, 2020, https://historyofknowledge.net/2020/02/12/gossip-in-the-archives/. Accessed 2 June 2020.

Leach, Joseph. Bright Particular Star: The Life and Times of Charlotte Cushman. Yale UP, 1970. ISBN: 0-300-01205-5

Markus, Julia. Across an Untried Sea: Discovering Lives Hidden in the Shadow of Convention and Time. Alfred A. Knopf, 2000. ISBN: 0-679-44599-4

Merrill, Lisa. When Romeo Was a Woman: Charlotte Cushman and Her Circle of Female Spectators. University of Michigan Press, 2000. ISBN: 0-472-10799-2

Newman, Sally. “Sites of Desire.” Australian Feminist Studies, vol. 25, no. 64, 2010, pp. 147–62. doi:10.1080/08164641003763014 .

Prell, Martin. “ps: ich bitt noch mahl umb ver gebung meines confusen und üblen schreibens wegen”: Frühneuzeitliche Briefe als Herausforderung automatisierter Handschriftenerkennung. Ein Transkribus-Projektbericht. 1 May 2018. https://www.db-thueringen.de/receive/dbt_mods_00034849. Accessed 13 Jan. 2021. doi:10.22032/dbt.34849

Wolf, Alexis. “Introduction: Reading Silence in the Long Nineteenth-Century Women’s Life Writing Archive.” 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, vol. 27, 2018, pp. 1–10.