Geraldine Jewsbury’s Passionate Rebuke of Charlotte Cushman

As the project is slowly drawing to a close (we’ll wrap up by September, *sad face*), we want to use some of our remaining time to highlight items in our collection that have stood out to us for various reasons – be that they were particularly challenging to read, fun to explore, romantic, sad, eye-opening …. . In a way, this will be a way for Selina and myself to reminisce about what we’ve done these past three years. Hopefully, for others it will be an additional tool to navigate the collection which has grown to almost 1000 items.

So, without further ado: my first highlight among our items is a letter written by Geraldine Jewsbury, presumably from 1846, addressed to Charlotte Cushman, in which she offers a stern rebuke of the actress:

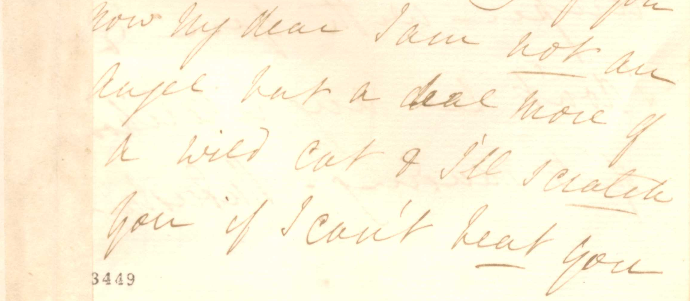

I am not an angel but a deal more of a wild cat & I’ll scratch you if I can’t beat you

Geraldine Jewsbury to Charlotte Cushman, Charlotte Cushman Papers, Library of Congress, 3449–3450, here: 3449

Jewsbury was a British author whom Charlotte met during her first tour of England. The occasion for this strongly worded letter? Jewsbury had heard from someone else (gossip!) that they had met with Cushman and she therefore knows that Cushman is travelling near her, but has neglected to let Jewsbury know that. The author demands that Cushman “will pass a day with [her] on [Cushman’s] way to Leeds.” I don’t know, if that ever happened. I do know, however, that Jewsbury was aware of Cushman’s romantic attachments at the time, since she mentions Eliza Cook – the poet, who was writing public poems as additional PR for Cushman’s tour (for more on how that played out, see Alexis Easley’s detailed analysis “Eliza Cook, Charlotte Cushman, and transatlantic celebrity, 1845–54″ (Easley et al.) – listed also in our secondary reading-recs). The letter ends with Jewsbury’s lament that

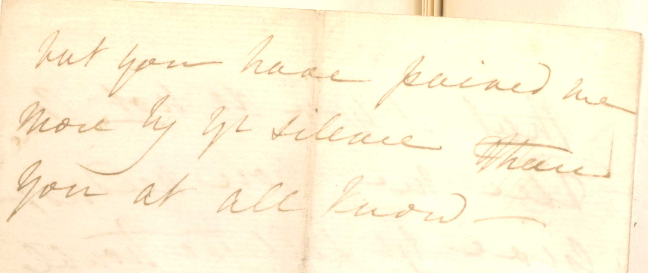

you have pained me more by yr silence than you at all know

Geraldine Jewsbury to Charlotte Cushman, Charlotte Cushman Papers, Library of Congress, Box 11: 3449–3450, here: 3450 reverse

The later letter reflects Jewsbury passionate attachment to Cushman and her rather “no filter”-attitude to writing – which also explains why Jewsbury was later hesitant to grant authorization to a request for her correspondence with Cushman to be quoted in the late actress’ biography. This we learn from a letter of which I like to think as a “companion piece” to the 1846-one, namely Jewsbury’s reply to Emma Stebbins from 1877. Stebbins had started working on the Cushman-biography immediately after the actress’s death in 1876 by asking various people for letters and for information (I’ve addressed Stebbins’ research process and her concern about a ‘lack of facts’ in my article on “Intimacy in the Archive” [Open Access](Horn).) That Jewsbury is among those referenced is noticed by reviewers, when Charlotte Cushman: Letters and Memories of her Life is finally published in 1878:

it is mainly for the story of her domestic life that the volume will be valued; for the correspondence with clever people, with Miss Jewsbury, Mr. Carlyle, Henry Chorley, &c., for the delightful journals of old times in Rome, still in those days a genuine old-world city, for the pretty pictures of her simple household, her quite “receptions,” her untiring energy to the very end. Memories pleasanter to read we have not encountered for some little time.”

The Graphic, Review of Stebbins’s Cushman Biography, Sept. 28, 1878 (link)

What reviewers might not have know, but what is clear both from Stebbins’ correspondence with people like Jewsbury as well as from the comparison between excerpt published in Charlotte Cushman: Letters and Memories of her Life and the surviving full letters, is the extent to which Stebbins ‘censored’ the more passionate passages in her sources so as not to jeopardize Cushman’s carefully build-up image of respectability posthumously. Jewsbury ends her response by reminding Stebbins that

“I trust to you that no names or +++ references of a personal nature shall be introduced – one writes carelessy & on the impulse of the moment one writes many things wh. one wd wish very much “to blot”!

Letter from Geraldine Jewsbury to Emma Stebbins, Feb 6, 1877, Charlotte Cushman Papers, Library of Congress, Box 11: 3462-3471, here: 3471 (link)

We can therefore assume that this is a letter written with more ‘care’ (read: self-restraint) than earlier correspondence, and yet, Jewsbury’s feelings about Cushman are rather out in the open:

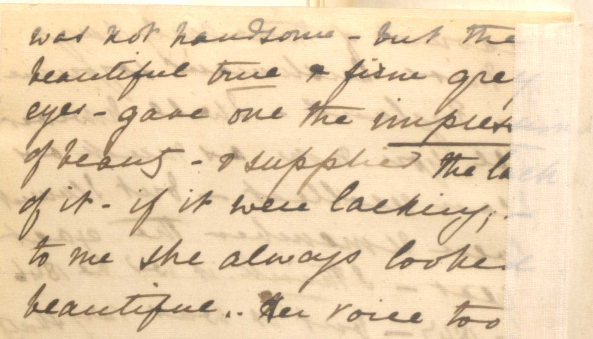

I suppose Miss Cushman was not handsome – but the beautiful true & firm grey eyes – gave one the impression of beauty. & supplied the lack of it. if it were lacking, to me she always looked beautiful.

Letter from Geraldine Jewsbury to Emma Stebbins, Feb 6, 1877 (link)

To return to the “wild cat”-letter: it is one of my highlights because it was one of my first “aha”-moments as I began working with the Charlotte Cushman Papers at the Library of Congress (like: wow, the level of palpable anger when writing a letter while hurt by your crush = absolutely on par with the level of palpable anger when texting while hurt by your crush). It was also one of my first attempts at transcribing nineteenth-century handwriting – and thus now stands as a throwback to before we starting working with Transkribus (though the full transcript was eventually produced by Selina with the help of Transkribus). Jewsbury’s letters is also a source that I’ve returned to for a number of papers (and now once more, as I sit down to write my monograph) for the way it highlights the web of relations among several women in Cushman’s life, how it gives us glimpes into how information travels in the 1840s (Jewsbury’s awareness of Cushman’s travel routes and of her private relationships), but also for how it can be connected to later letters and thus how it can be used to stress the interconnectivity not only of people, but of sources. Its glimpses into Jewsbury temper and into the often overlapping relationships in Cushman’s life connect it not only to other letters by Jewsbury herself (such as the one addressed to Stebbins), but also to correspondence by Jewsbury’s and Cushman’s mutual friend Jane Carlyle. Carlyle, for example, describes her “row” with Geraldine Jewsbury, whom she describes as “that sort of emotional woman,” in a letter to Cushman from 1862. The rather complicated beginnings of their three-way-friendship are hinted at in this letter from 1846, in which she Carlyle shows signs of jealousy over Jewsbury infatuation with Cushman: “Geraldine by the way is all in a blaze of enthusiasm about Miss Cushman the Actress—with whom she swore everlasting friendship at Manchester just when she had got jealous of me and Mrs Paulet—Ever since her letters have been filled with lyrics about this woman—till I could stand it no longer—and have written her such a screed of my mind as she never got before.” Compare this to Jewsbury’s insistence to Cushman that “I am in the devils own temper with you & I don’t see any likelihood of its mending.”

For those intrigued by these letter exchanges and looking for more context, I recommend Julia Marcus’ Across an Untried Sea. Discovering Lives Hidden in the Shadow of Convention and Time – and, of course, further letters by these three women collected in our collection and elsewhere). For those intrigued by the spotlight on some highlights from our collection, I recommend checking back again next month, when it will be Selina’s turn to pick favorites.

Reference List

- Easley, Alexis, et al., editors. Researching the Nineteenth-Century Periodical Press. Routledge, 14 July 2017. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315605616.

- Horn, Katrin. “Of Gaps and Gossip: Intimacy in the Archive.” Anglia, Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 15 Sept. 2020, pp. 428–48. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1515/ang-2020-0037.