"Queen's Theatre.— Miss Cushman. 'The Scornful Lady.'", Manchester Examiner and Times, Jan 2, 1849

Dublin Core

Title

Subject

Description

Credit

The British Library Newspapers, Gale Digital Collections

Source

Publisher

Date

Type

Article Item Type Metadata

Text

QUEEN'S THEATRE. —MISS CUSHMAN.

"THE SCORNFUL LADY."

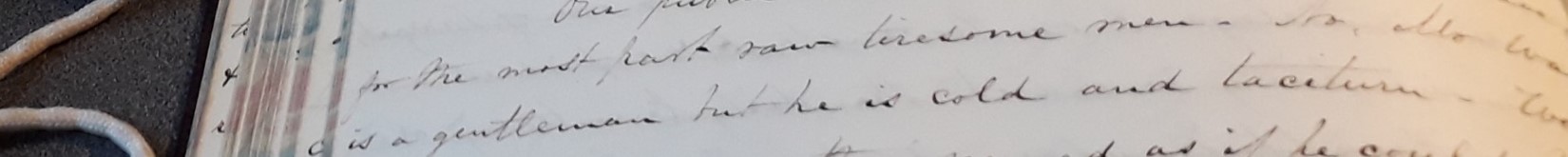

If the "legitimate drama" be dead, it revives again upon occasion. Beaumont and Fletcher's play of the Scornful Lady, which, as the papers tell us, "has not been acted for a hundred years," has woke up like the sleeping beauty, and opened its eyes on a very changed order of things. Whether it will feel sufficiently at home to live another natural life out before it sleeps again, the event must determine. It has been curtailed and refined to meet our notions of "common decency", and there is nothing left us to complain of, except a certain vagueness, which prevents our comprehending the plot, or knowing for some time what the piece is about. The dialogue is solid and sparkling, and the texture of it so close, that the incidents are not marked nor emphatic enough in proportion. There are too many secondary characters introduced, and the subordinate plot is almost as prominent as the principle one, so that unless very strict attention be paid to each scene, it presents a somewhat rambling and confused aspect to the audience. The shades of character and the wit of them, are too delicate and subdued to arrest the idle or wandering attention. Still there is a great charm about it. It has a smack of reality. It is redolent of the manners and feelings of the day in which it was written; it has that indescribable impress which the present gives to every work that is done in it, and which no amount of reading, or learning, or cleverness can imitate in another age. It is saturated, at every pore, with a mode of life now passed away, and replaced by another spirit, which, in like manner, interpenetrates every work, and stamps it with the individuality of to-day. There is all the difference between a book written in times of which it treats, and a play or a novel cast in that period, that there is between the real aspect of a country and its inhabitants, and the most correctly appointed bal costumé. The most remarkable point about the old dramatists is the wonderful profusion of their characters and incidents, which are not in the least rounded off nor interfered with by the wooden horizon of the "five nets," which circumscribes our view. We feel that they began to live long before we saw them, and that those who escaped the casualties of the piece, will go on doing the same long after we lose sight of them. The play ends, but they do not end with it, and except for the convenience of time the play might be continued, and fresh scenes be constantly unveiled till death came to close their history.

The story of the piece (for the benefit of such of our readers as are ignorant of the original and have not seen Mr. Serle's version of it) is briefly thus :—A lady of good birth and great possessions quarrels with her accepted lover when she is on the point of marrying, because he has been too forward in his behaviour in public, and boasted of the favour she had shown to him. Albeit that she is in love with him, she breaks off the engagement, enjoins him to go and look on "Dover's dreadful cliff," travel and learn manners, for the space of a twelve month, and then permits him to return and begin his suit afresh. That is no help for it. The poor man sets his house in order, leaving his younger brother three hundred pounds to support the credit of the family for the twelve months. This younger brother, a true descendant of the prodigal son of the parable, brings dissolute company into the house, and drives the old steward, who had been enjoined to keep order, first to distraction, and then to drink. This is a curious picture of the "bad company" of the days of Beaumont and Fletcher. The elder brother returns disguised, and announces his own death, as having perished at sea, to his obdurate mistress, who is cut to the heart with remorse for her cruelty. Miss Cushman, as the Scornful Lady, gave this scene most admirably; her genuine burst of grief when she believes his death, was most touching, and a sudden transition for one moment to intense happiness, when she sees the trick that is being put upon her, followed like lightning by the devil of coquetry, which possesses her with seven-fold strength, for her momentary relenting was given with a heartfelt mischievous glee, which made one quite forgive any freak she might choose to play; and the air with which she wipes her eyes and puts up her pocket handkerchief, declaring herself resigned, as weeping could not bring back "her lost and lovely Loveless"— the comic function with which she declares her intention to lead a new life, and show her reformation by proving how well she would love his successor, was a charming piece of comedy and genuine fun, which it did one's heart good to see. During the absence of Loveless, another suitor has come to try his fortune, and has been well and hospitably received, though without any chance of success, for with all her coquetting and scornfulness the lady has a lofty and loyal soul, and the thought of inconstancy never occurs to her. But for now, the new suitor is sent for, and treated, before the eyes of the disguised a Loveless, in a way to drive any man mad. He incontinently reveals himself, and gets jeered and tormented, and sent about his business in return. The new suitor, however, derives no advantage from it; he is rigorously reduced to the sternest discretion. It requires nice acting to make the Scornful Lady interesting; but Miss Cushman made her a most womanly and charming creature, and furnished an apology both for her own perverseness and the fascination of her lover. There were little touches in her bye-play which revealed a whole world of sterling good-heartedness. Loveless and despair, obtains another interview with his mistress for the sake of easing his outrage sensibilities, by giving her a good scolding! Nothing but the "extenuating circumstances" can excuse the ungentle and uncourteous mode in which he rails at her, until she swoons with fear that she has lost him forever; then he is, of course, very sorry for his violence, which, she perceiving, and reassured of her empire, the devil of perverseness enters into her again, and she make one sorry for the poor man exposed to the pitiless hailstorm of her sarcasm; but, as in all quarrels between lovers, where the woman is really in love, the woman suffers most. She drives him from her, indeed—but she feels she has gone too far—he will not listen to her recal, and leaves her regretful and relenting. Miss Cushman gave all the shades of temper and changes of mood in the scene admirably, and with a dignity that must have secured sympathy from all the women, at least all who were present.

Poor Loveless has other chagrins also; he comes to life again only to see how well people could do without him; and he is just in time to rescue his estate from the hands of an usurer, who was buying it for next to nothing, ready money. We need not pursue all the subordinate plots and characters. The ladies chaplain shows us the melancholy state of contempt in which the inferior clergy were held, especially those attached to great households, to say nothing of the disgusting laxity of morals indicated. The theology and divinity of that age might be Orthodox, and scepticism on those points, was not tolerated as we know; but cruel and ribald jesting on the utterer of sacred mysteries has always been the precursor of the dissolution of the "Ages of Faith."

The Luckless Lady, in her repentance, sends to Loveless, but he refuses to hear, though his own heart is nearly broken, and, in spite of his rage, he would give his hand to be reconciled. He hits on a new and somewhat clumsy device. He persuades her rejected suitor to disguise as a woman, and go with him as his bride, and so moved the lady behind her power to recal what she may say. In spite of the most palpable appearances, the Scornful Lady is deceived. She humbles herself, coaxes, entreats, to lure back the "tasselled gentle" she had so heedlessly let go. This scene also was well given; though all the parties concerned were too violent for our taste, still it was spiritedly done. The Lady is cozened and fairly married, to her great delight, safe from her fancied rival. Her anger struggling with her deep affection, when she is told the snare she has fallen into, is very natural, and Miss Cushman gave it with great delicacy. The concluding scene, where her sister and the disguised Welwood agree to be secretly married, tells very well and is a great improvement on the original. It makes a very pleasant and effective ending. The prodigal brother reforms and marries a rich widow, to whom the userer who has cozened him was paying his addresses. So political retribution is effected in that quarter,—the unlawful companions are turned out,—the discarded steward pardoned, and the curtain drops on a very promising outlook for all the parties. Almost we credit the nursery legend if they "all happily lived ever after."

Of the other actors in the piece, we can only say that they acted with spirit and intelligence, though occasionally too boisterously. The elder Loveless ought not to forget that he's a gentleman, and that, even in his rage, he must remember courtesy. The characters were, on the whole, dressed well; the costume is of the time of James I. and some of the scenes were pretty, although not new.

Saturday evening was the close of Miss Cushman's engagement, the play being Bulwer's Lady of Lyons, in which we have always discovered much artistic cleverness of writing, along with the usual absence of that higher moral tone—that stern quality of truth do conspicuous in the writings of our elder dramatists, however the latter may be occasionally disfigured by grossness of form or manner. In the character of Claude, for instance, and in the development of that part of the plot on which the whole moral of the play rests, we find the gilded glory, after all, more prominent than the reality; —the epaulets and the colonelcy redeem the previous trick played upon by the Lady; the worldly-minded Madame Deschappelles, who sticks to the tinsel throughout, appearing about the only consistent character in the piece. The part of Claude is well adapted to Miss Cushman's peculiar powers—there is a romantic energy about it, in the expression of which she is always successful. We liked her the best in the earlier scenes, as the young artist, where the feelings are so fresh and warm, now gushing forth like a clear well-spring, anon dashing like an intercepted torrent through its torturous and rugged confines. Whatever the critics may say as to the manner of doing these things, there is a poetry and passion about them, rarely to be met with the commonplace of modern acting.

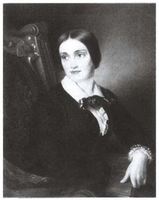

The character of Pauline introduced to us Miss Matilda M. Hays, a lady whose name will be familiar to many of our readers, as the editor and principle translator of the recent edition of the works of George Sand (Madame Dudevant). Miss Hays, we learn, has taken to the stage as a profession, within a few weeks only, under the direction of her friend, Miss Cushman. Her performance of Pauline, after so limited a noviciate, gives much promise for the future. Tall, with fine features, good figure, and graceful carriage, there is a total absence of all those stage mannerisms to which we are accustomed; a novelty of style which gave great reality to the quieter passages of the play, throwing an interest over them that a more studied manner—mere acting—seldom attains. Her title of the Lady of Lyons was fairly worn and won; it was not the lady of the stage, but that of the drawing room,—a character much wanted in the theatrical world, and one which Miss Hays would do well to cultivate. We should much like to see her in some of our higher class of comedy, where we doubt not that, along with the advantage of a little more stage practice and study, she would very soon take a position far above what we are accustomed to see in the representatives of the accomplished lady. There is no lack of feeling either on the present occasion, but it was sometimes marred—if we may be allowed to be critical where all was so pleasant and promising—by deficiency of physical power. Her voice is "soft gentle and low: an excellent thing in woman"—and by an elocution too monotonous in tone, too brief in marking, we missed the occasional rolling periods, so important in the delivery of dramatic poetry. These are points which the practical knowledge and the poetic spirit of her instructor and friend will soon discover and as easily amend, for there is evidently the important groundwork for intelligence and feeling. Many of her scenes appeared greatly to interest her audience and to call forth their sympathies, which were finally evinced towards both ladies by the usual compliment of "a call" at the fall of the curtain.