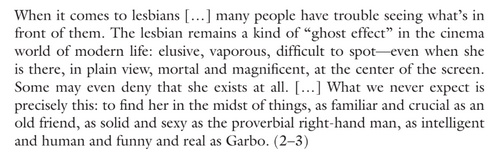

In letters, scraps of notes or a diary entry, we are offered some of the most fragmented and ephemeral textual traces of a life and the intimate connections that structured it. But while we sometimes conflate the private and the confessional, there is no guarantee that what we will find preserved within someone’s personal papers will necessarily offer clarity of insight or confirmation of intent.

(Dever et al. 122)

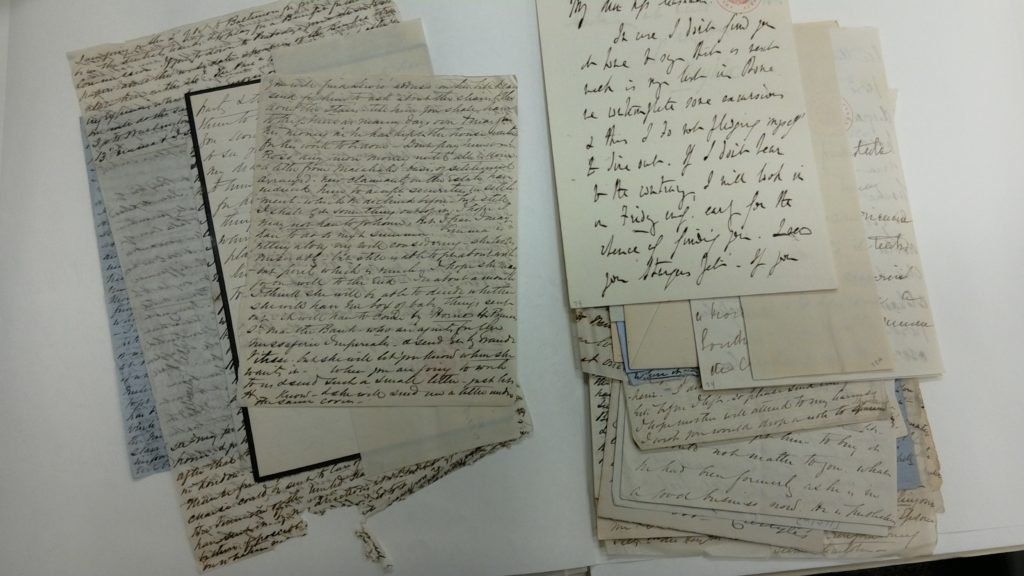

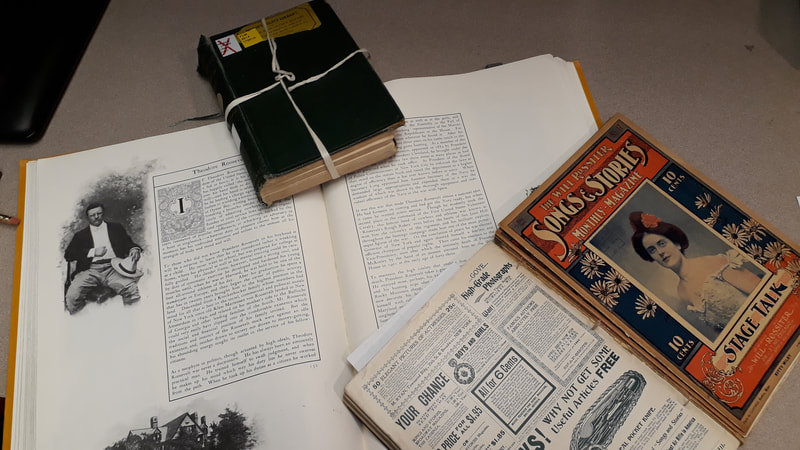

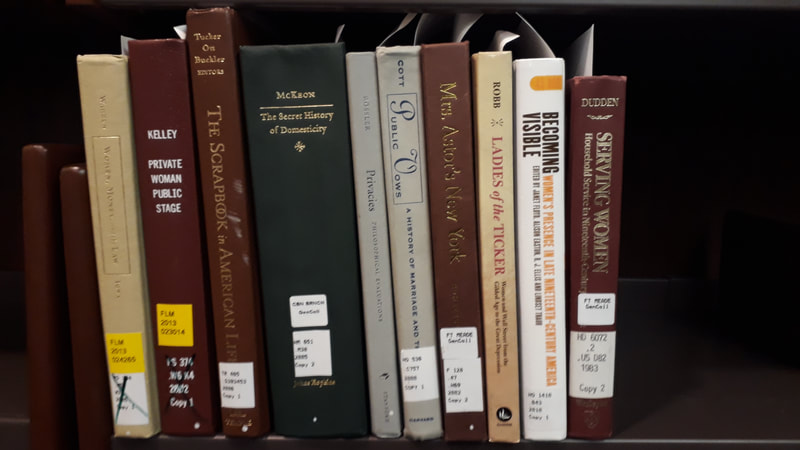

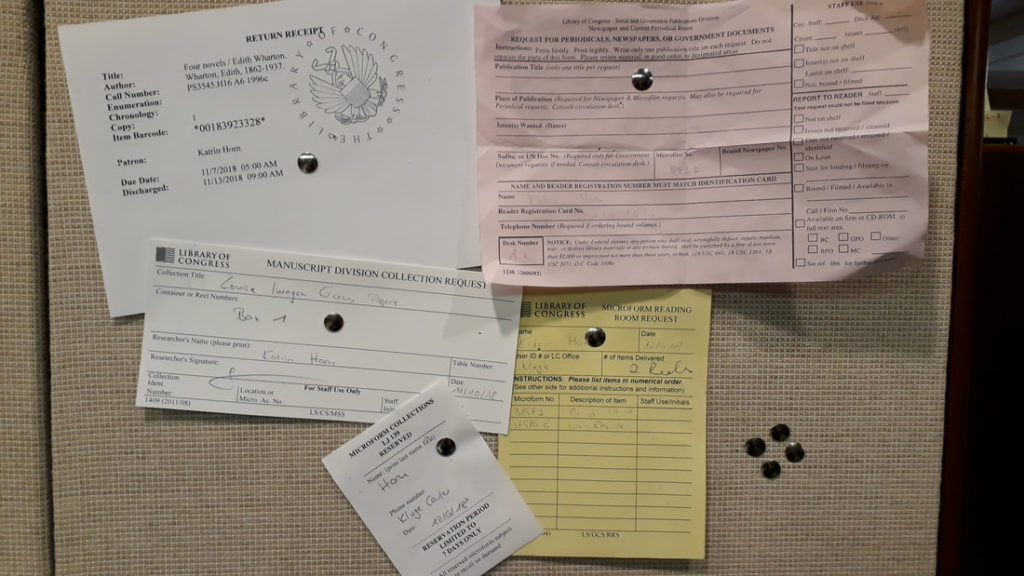

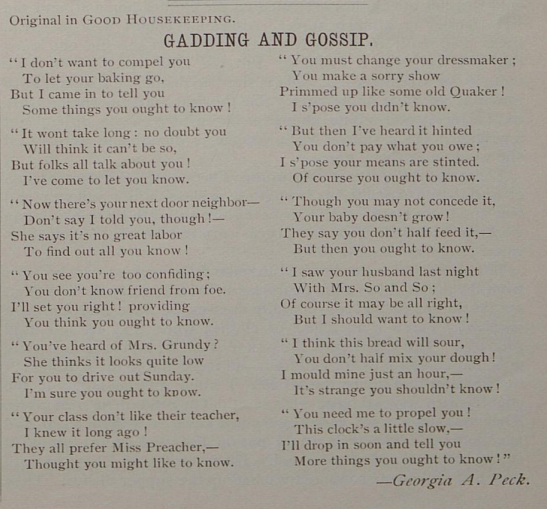

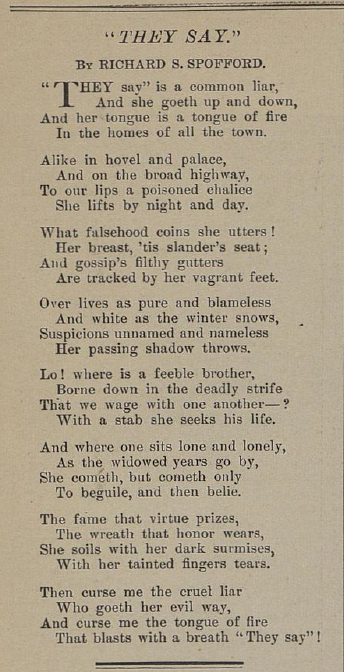

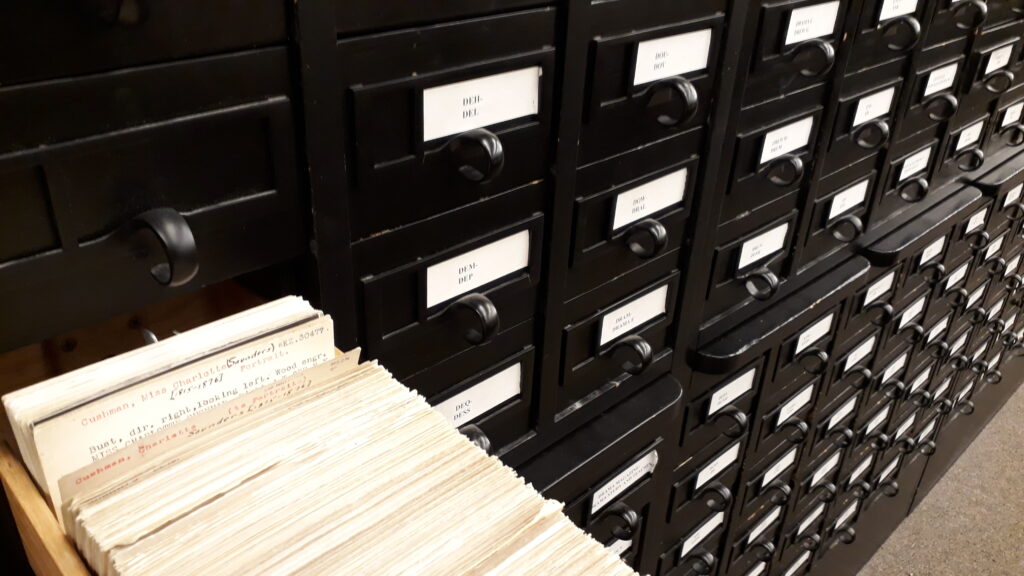

In our research on Charlotte Cushman in terms of gossip and reputation management, we mainly work with archival documents with intimate knowledge. They do not necessarily “offer clarity of insight or confirmation of intent” (Dever et al. 122). but implicitly touch upon Cushman’s ambition to construct a most favorable public image of herself as a respectable and successful actress. For instance, Cushman wrote to or received long letters from her romantic partners that inform the correspondent about press reports, attempts to conceal certain parts of her private life or build a network in foreign countries such as England and Italy between the 1840s and 1860s. Additionally, many of the biographies and articles we deal with often build on intimate knowledge. Today, I introduce a blog series that revolves around the perks and intricacies of archival research, and takes into consideration the form of intimate knowledge that is constitutive of gossip. We will post a small series of entries covering the topics of accessing archival documents, deciphering them, and working with/creating intimate, archival narratives.

While Katrin Horn’s blog post to the GHI blog ‘History of Knowledge’ discusses the significance of gossip as a form of knowledge, this blog entry engages with practical questions and implications for our archival research, which address tacit knowledge and a woman who polarized her audiences transatlantically both on and off the stage. Issues range from accessing and deciphering archival documents to making use of intimate knowledge accounts.

Read more