Dublin Core

Title

Subject

Description

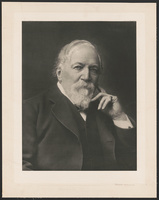

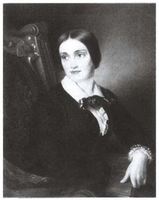

Besides her art, she is most well known for masculine attire and activities. Both her father, "Dr." Hiram Hosmer, and Harriet do not conform to gender norms. Hosmer moves to St. Louis (Missouri Medical College) in 1850 and is friends with Wayman Crow who supports her social standing. In October 1851, Harriet visits Charlotte Cushman in Boston, after Cushman's first farewell tour in the US. She is close to Charlotte around 1852. In that year, she is part of the group including Charlotte who moves to Rome. Hosmer stays in Rome until the summer of 1857. Harriet Hosmer and Charlotte Cushman live together again in Via Gregoriana in Rome from 1860 to 1865. In 1865, Hosmer moves to 26 Via delle Quattro Fontane. In April 1862, her father dies which eventually brings her closer to Wayman Crow on a professional base, although they have been close friends for a longer time.

She is supported by William Wetmore Story, the Brownings, and Charlotte Cushman. Elizabeth Barret Browning is particularly taken with her. In a letter to English author Mary Russel Mitford, she described Hosmer as "a great pet of mine and Robert's [...] who emancipates the eccentric life of a perfectly 'emancipated female' from all shadow of blame by the purity of her's. She lives here all alone (at twenty two) as Gibson's pupil, (while her father lives in America), – dines and breakfasts at the caffés precisely as a young would, – works from six oclock in the morning till night, as a great artist must" (May 10, 1854; qut. in Meredith B. Raymond and Mary Rose Sullivan (ed. and introd.), The Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Mary Russell Mitford, 1836-1854, vol III: 409)

In the 1860s, she is exposed to slander about her Zenobia statue. Rumors are spread, especially by The Art Journal and The Queen, that she has not been the statue's creator. Hosmer defends herself publically in the Atlantic Monthly (Dec 1864) with her article "‘The Process of Sculpture," in which she aims to "correct the false but very general impression, that the artist beginning with the crude block, and guided by his imagination only, hews out his statue with his own hands."

Hosmer is romantically linked to a number of women, among them Lady Ashburton and, most importantly, Emma Crow's sister Cornelia Carr. Carr publishes Harriet Hosmer: Letters and Memories (1912). Despite Hosmer's long presence in their shared household, Stebbins refers only once to Hosmer in Charlotte Cushman: Her Letters and Memories of Her Life (1878).

To nineteenth-century readers, Hosmer also appears to be the real-life model for Hilda in Hawthorne's The Marble Faun. In this preface, Hawthorne notes: "Where [the author] capable of stealing from a lady, he would certainly have made free with MISS HOSMER'S admirable statue of Zenobia" (Riverside, 1903: xxv).

Type

Person Item Type Metadata

Birth Date

Birthplace

Death Date

Nationality

Occupation

Secondary Texts: Comments

'In 1869 the friendship between the artist and Charlotte Cushman suffered irreparable damage. The faults in the foundation had been there for years, probably since Emma Stebbins first moved into the Cushman household, and the distance between the two women had grown after Harriet established her own home. It must certainly have been hard for Harriet, who loved to be - and expected to be - the center of attention, to see the actress shower another with her affection and influence. The final break, however, did not explicitly come from a fight over patronage. As so often happens in personal relationships, the underlying tensions were exposed by a seemingly trivial, even ridiculous, matter. Harriet and Ned Cushman joined together to protest the fact that in the foxhunts that were held regularly outside of Rome, Americans never won the highest honors, and the two withdrew from the events. But when Prince Bandini asked Harriet to return in 1869, she accepted, even though the invitation was not extended to Ned as well. Charlotte Cushman, who was suffering from breast cancer at the time, was livid. The fight escalated when Harriet, insulted by the actress when visiting her, refused to invite Cushman to a dinner she gave for the Longfellow family. When the Cushman household left Rome in the summer of 1869, none said goodbye to Harriet. Eventually a partial reconciliation came about, but the friendship never fully recovered. Still, even at her moment of greatest anger Harriet acknowledged that she was 'always ready and willing to testify to my great indebtedness' to Cushman." (Culkin 116)

In Hosmer's biography, Culkin comments on Hosmer's relationships with other women: "Throughout her life, Harriet had had flirtations with females, but the woman she seemed closest to had always had another partner. Charlotte Cushman was involved with Matilda Hays and then Emma Stebbins; Cornelia, despite the intensity of her friendship with Harriet, married Lucien Carr. Harriet's relationship with Marion Alford hay have started as a flirtation, but quickly evolved into a friendship. With Asburton, Harriet had the longest-lasting romance of her life, with a woman she could claim as hers. The relationship had enormous consequences for the artist - emotionally, professionally, financially, and geographically." (Culkin 117)

In her monograph on Charlotte Cushman, Merrill states that "Charlotte and Matilda together embodied a degree of female independence and an alternative style of living that Hatty had never seen before" (169).

Controversy about the Hosmer and Cushman relationship among scholars:

- Krisher writes that Hosmer's and Cushman's relationship lasted from 1858 to 1865 (154).

- In contrast, Culkin, Hosmer's latest biographer, does not believe in a romantic relationship between Hosmer and Cushman: “A spark of attraction between Cushman and Harriet most likely helped spur the friendship so quickly, but both often cast their relationship as that of mother and daughter. Cushman was deeply involved with Hays, and the draw for Harriet may have been to the promise represented by Cushman's life with Hays as much as to the woman herself. The great actress allowed her to see as a real possibility a life that included professinal success and a devoted, passionate relationship with another woman.” (Culkin 23)

Sherwood claims that Hosmer was greatly indebted to Charlotte Cushman (300). Culkin describes Harriet's father, Greenwood, and Cushman as Harriett's most important advocates in Italy: "Greenwood represented the writers who promoted the young artist in the American press, another critical part of Harriet's quick rise to fame. Greenwood had achieved popular success with a regular column published in the Saturday Evening Post and the National Era had hired her to document her trip abroad through "a series of Letters form the Old World"; thus Harriet's debut in Italy was chronicled in a national publication. From the second she entered Rome, then, the people of the United States were following the sculptor's progress. … Harriet's network made her first days in Rome much easier. Cushman established a house for her party at 28 Via del Corso, giving the sculptor a base near the Spanish Steps, the heart of the expatriate community." (Culkin 29)

Culkin repeatedly writes about Cushman's decisive and planned contribution to Hosmer's career: “Charlotte Cushman was especially adept at using an active social life in Rome to spread the word about the young artist. The actress hosted weekly salons at her house, introducing Harriet to the most notable names in Rome, and Cushman and her housemates were also invited to other social events. Cushman did not simply introduce Harriet to expatriate society at these occasions; she also actively solicited support for her friend.” (Culkin 31).

The Stebbins and Hosmer relationship is presented as ambivalent. Additionally, the secondary texts seem contradictory about how to categorize their relationship, as is exemplified by two excerpts from Culkin and Merrill.

- “When Harriet returned from her trip to the United States, she joined the household, which included Sallie Mercer (Cushman's longtime maid) and a series of Cushman's friends. The home was not without tensions. In a letter to Wayman Crow, Harriet declared she had "taken unto myself a wife in the form of Miss Stebbins, another sculptrice & we are very happy together." [HH to Wayman Crow, December 9, 1857, HGH Papers, folder 94, reel 3] As with Hays, Harriet and Cushman once again seemed to compete for the attentions of another woman, even as they primarily cast themselves as mother and daughter. The friendship survived, although Stebbins clearly chose Cushman as her partner. Beyond a romantic rivalry with Cushman, Harriet must have also felt a professional competition with Stebbins. For five years Harriet had been the sculptor of the house and had enjoyed Cushman's powerful endorsement, which had helped her conquer the expatriate social scene and develop her career. Cushman, for the time being, would continue to endorse and promote Harriet, but her energies and influence would also go toward Stebbins.” (Culkin 61)

-

"The affinities and contradictions present in a house full of women who love other women were more complex than a mere replica of a heterosexual and nuclear family, even if that was the only language available to describe their ties. Witness, for example, some of the ways Hays used the word wife. When Hattie first came to live with the more stereotypically feminine Emma Stebbins, she wrote t Wayman Crow that she had "taken unto myself a wife in the form of Emma Stebbins, another sculptrice and we are very happy together." But Emma Stebbins was living with both Hatty and Charlotte. While Hatty's depiction of Charlotte's partner as her own "wife may have been a reflection of Hatty's (unconscious) feelings of competition with Charlotte, it may have also afforded Hatty a way to differentiate her own professional aspirations with their household from those of Emma Stebbins. Hatty never used the feminine diminutive "sculptrice" to describe herself, and her playful invoking of gender in this letter may imply as much about Hatty's perception of herself as a serious (male), professional sculptor, when compared with the feminine, domestic "wifely" Emma, as it does the closeness of any relationship between them. Although women in their era might unabashedly liken their relationship with other women - whether as friends or as lovers - to heterosexual marriages, secure in the belief that to most readers this allusion would be read as a signal of affectionate friendship rather than sexual passion, still the terms also contained the possibility of invoking "wifely" or "husbandly" sensual and sexual bonds as well as the strictly sentimental." (Merrill 189)

- While Emma and Charlotte shared "Charlotte's quarters, ... Hatty's rooms were her own." (Merrill 189).

- "The female artists were friendly with one another; and many lived on Via Gregoriana. Harriet had a flirtation with Florence Freeman; although Cushman claimed Harriet threw her over for Mary Crow, the end of the romance did not signify the end of the friendship […]. […] Despite their bonds, however, the women also competed for patrons, commissions, and publicity. Lewis, in addition, faced racism and condescension even from those in the community who puported to support her. […] Between Harriet and Stebbins the tension was personal as well as professional. Cushman's devotion to another sculptor surely hurt Harriet, who had grown used to Cushman's attention and support. The rivalry intensified after the Massachusetts legislature passed a resolution in the fall of 1859 to install a statue of Horace Mann in front of the State House in Boston. A competition was held to award the commission, and Harriet lobbied hard to win it, writing to Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, Mann's sister-in-law, to ask for her endorsement. The professional ramifications of Harriet's changing personal relationships became clear when Cushman backed Stebbins in the competition and courted Mann's widow, Mary Peabody Mann, by promising to help raise money fr the work through a dramatic reading of a euology of Horace Mann. In the summer of 1861 Stebbins emerged victorious. By the end of the year, Stebbins also received the commission for a statue of Commodore Perry for New York's Central Park, which was never completed, and was in negotiations to create Betheseda Fountain for the same park. Cushman wrote of Stebbins' good fortune to Emma Crow, adding, "Don't say anything about it for it only makes unnecessary jealousies. Don't tell Mary [Crow] for I don't want Hattie to know of it." [CC to ECC, July 26, 1861, CCP]" (Culkin 96)

- "She convinced the prominent St. Louis businessman Wayman Crow to order a crayon portrait of Harriet Hosmer by Emma Stebbins." (Parrott 324)

- "They were high-spirited and unconventional in their behavior. In 1861 Cushman described in an amusing letter to Emma Crow back in Saint Louis the pistol-target practice of Emma Stebbins and Harriet Hosmer she had witnessed in Stebbins studio" (Parrott 331)

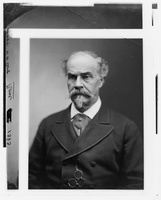

Hosmer's and Wayman Crow's professional ties: "

"Her father's death changed Harriet's life in a practical way as well. She was his sole heir, and thus she now had another source of income. Dr. Hosmer had for a time arranged for a male cousin, probably Alfred Hosmer, to oversee the estate. When she found out and protested, her father rewrote his will so the inheritance came directly to her. Harriet needed money, and Cushman, noting the timing, commented, 'I never saw a person who was so universally fortunate in m life & sometimes I think it is a reward for her being so universally cheerful.' [LoC CCP, CC to ECC, May 7, 1862] The death also linked Harriet more closely to Wayman Crow, who would now play an even larger role in managing her finances." (Culkin 67)